Devious Diptera

Written by Jonathan Wojcik

Thomas Shahan

Some of them eat feces, some of them suck blood, and some of them are responsible for spreading the deadliest diseases known to man. They're the gnats, mosquitoes and "true" flies, insects of the order Diptera or "two winged" insects, and have caused more trouble for Homo sapiens than perhaps any other order in the animal kingdom. Of course, with over 120,000 described species and more than twice as many estimated to exist, the flies are an extremely varied bunch, adapted to every environment where insects thrive and some where they normally don't.

Thomas Shahan

While you're obviously more likely to encounter the species who like to bug us, the majority of flies have no interest in our bodies or our homes and include key pollinators for thousands of plant species, such as the precious cocoa tree - pollinated exclusively by a fungus gnat - and over 100 other cultivated crops. Predatory and parasitic flies are integral to the regulation of other insect populations, and even the hated trash-eating flies provide a valuable service by - fancy that - eating trash. In fact, flies are the terrestrial world's most widespread and most effective janitorial crew, quickly gobbling up the majority of carrion and other decaying organic matter before it can become a natural biohazard.

All true flies undergo a complete metamorphosis, most species beginning their existence as the larvae we call maggots. Everybody loves to harp on these little guys as one of the "grossest" animals in nature, but it's hardly their fault that they're so small, numerous and squirmy. They need to be, or they wouldn't do their jobs so well. Nothing cleans up a rotting carcass as quickly and thoroughly as a million little mouths on minimalist, conical bodies, using their tusk-like hooks and digestive salivary secretion to strip the last scrap of meat from the last glistening bone. It's Mother Nature's patented stain-lifting formula - it can even get those stubborn squirrel smears out of asphalt.

Brian V.

Adult flies are distinguished from nearly all other flying insects by having only their front wings adapted for flight, the rear wings having been reduced to knob-like organs called "halteres," which actually function as gyroscopes to maintain the insect's aerial balance. The mouth parts of a fly can only take in liquids, but are adapted to a broad variety of diets; many species famously regurgitate digestive enzymes to liquefy solid foods externally, soaking up the mush into a sponge-like pad. Parasites like horseflies use a set of serrated blades to saw through flesh and lap up blood, while mosquitoes employ a delicate drilling and siphoning system. With their often very brief adult stages, however, not all flies have time to eat or even have mouths, and for that matter, not all flies can even fly. The Diptera have taken forms even stranger than the most divergent beetles, and by the time we're done, you're going to either love them or hate them like you never have before. Preferably the former.

Vampire Maggots

Everybody knows about blood-sucking flies, but blood-sucking (hematophagous) maggots are surprisingly obscure. Larvae of a single blowfly genus, Auchmeromyia, share the same feeding habits as bedbugs, hiding in the bedding and nesting materials of mammals during the day and emerging at night to drink blood from sleeping hosts. Auchmeromyia senegalensis, commonly called the "congo floor maggot" (more photos here) prefers the blood of us humans, but unlike bedbugs, they are completely unequipped for climbing. A bed held off the ground by an ordinary frame will stop the little ghouls in their tracks, and has significantly reduced their prevalence in human homes.

Snow Flies

Colin Purrington

The first of many wingless flies (walks?) on our list, Chionea are part of the crane fly family, and among the world's few insects at home in the ice and snow. In fact, Chionea flock to the coldest spots they can find, and can survive at some of the highest altitudes of any macroscopic animal thanks to the natural antifreeze (glycerol) present in their hemolymph (insect blood). Use of wings would not only get them blown away in powerful winds, but quickly expend energy and heat in fatal amounts. Adults may drink water by pressing their faces into snow but are not known to eat, while larvae feed on dead vegetation, moss, lichen and animal droppings.

Stick Ticks

Artour A

We don't often hear about tinier insects drinking the blood of larger arthropods, but many tiny midges specialize in just that. Some, like vampire bats, come and go from their hosts. Others, like members of the subgenus Microhelea here, lose their wings as adults and anchor to their victims like ticks or leeches.

Crab Flies

Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology/Stensmyr

A great example of the ultra-specific environments some insects can adapt to, Drosophila endobranchia is a species of "fruit" fly that seems to breed exclusively in the mouths of land crabs. The maggots are not harmful parasites, but feed on bacteria and mucus until they crawl onto the crab's face and metamorphose into adults. Males seem to fly poorly and rarely even attempt to do so, staking out a prime standing spot on the crab's face and defending it from rivals. Females, seen less often, are thought to take wing after mating and find new crabs to colonize.

Phantom Midges

Vernalpool.org

As adults, the phantom midges resemble tiny, feather-faced mosquitoes and may feed on only nectar or never feed at all, living only long enough to mate and die. Like several entries on our list, it's the larval stage that makes Chaoboridae stand out; a fully aquatic predator propelled by delicate "fins" on its tail. Unlike any other known insect, the antennae of this transparent killer are modified into mantis-like claws, used to impale such prey as fairy shrimp or mosquito larvae.

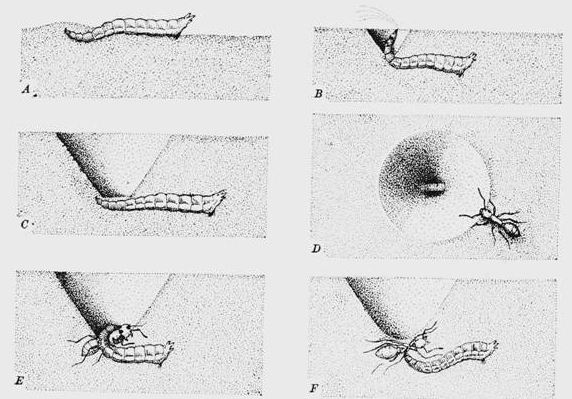

Wormlions

By Beeinformed

The larval stage of antlions are famous for excavating treacherous pits in loose sand, waiting at the bottom for unsuspecting insects to tumble into their hungry jaws and even throwing sand to make escape more difficult. Antlions are not Diptera; their adult stage is four-winged, and belongs to the order Neuroptera. Vermilionidae or "wormlions," on the other hand, are true flies whose larval stage has strikingly evolved an identical hunting strategy, including the sand-hurling attack. The sticky, hairy body of this tiny sarlacc collects a layer of sand to become almost invisible at the base of the trap, and lacking the long jaws of an antlion, it clamps prey between its tiny fangs and a small sucker on its barb-covered rump.

Marine Midges

Despite representing the majority of life as we know it, insects are technically absent from the majority of the planet Earth itself, as the only insects known to inhabit seawater are a few Water Striders (true bugs) and the four known species of Pontomyia, the intertidal midges. Larvae can be found among the rocks and corals of shallow tide pools, feeding exclusively on certain species of algae or seagrass. The adult female is wingless, limbless and still very maggotlike in appearance, while the adult male is unlike any other insect. He cannot fly, but his reduced, paddle-like wings blow him across the water's surface like a hydrofoil, skating on the tips of only his two middle legs. He will use his other limbs to carry a female and mate on the move, sometimes even helping strip away her pupal skin. The entire adult life of the male is only a few hours, much shorter than the famously short-lived mayflies (which are not Diptera), and he lacks a mouth, as he will never have use for one.

Ant-mugging Flies

Photo copyright Alex Wild

When a hungry ant requires emergency sustenance, she finds one of her sisters and strokes her face with her feelers in an intimate signal unique to every ant species, triggering the involuntary regurgitation of stored food. It's a secret ant handshake that says "puke in my mouth!" and Milichia patrizii is just one example of a non-ant that has cracked the code. Uniquely, it uses its own antennae as a pair of clamps to grab an ant's feeler, then uses its sponging mouth to tap out the password. Once it slurps the predigested goo from the ant's jaws, it flies away and leaves the ant in a temporary daze.

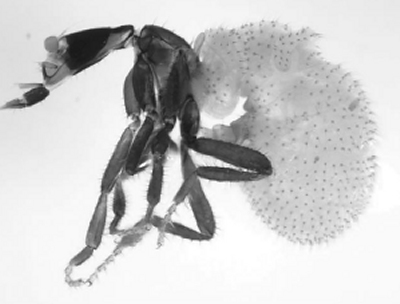

Ant-eating Slug Maggots

Photo copyright Alex Wild

Another tormentor of ants, this fleshy dome is a highly unusual maggot which lurks deep within their underground colonies, protected by its thick, shield-like back while it eats its daily fill of ant eggs or grubs. When these little critters were first discovered, their slug-like appearance and movements got them classified as mollusks, but subsequent specimens were observed metamorphosing into hoverflies. Several different hoverfly species share this type of larval stage and are currently grouped together as the genus Microdon, but may in fact represent several groups who stumbled onto the same survival strategy. The orange tube on this one is the breathing snorkel on its rear end, while the mouth is on its underside.

Bee Lice

Imagine dealing with a literal monkey on your back. A tiny, hairy little gremlin whose barbed claws hold tight no matter how you shake, twist or pull. Worst of all, whenever the little bastard gets hungry, he climbs down your face and forces you to vomit, lapping up a few drops of your last meal as it congeals on your shirt. Such is the suffering of a honeybee at the tiny hands of the "bee louse," Braula coeca. Taking things much farther than the ant-mugging fly, this wingless parasite lives directly on its bee host and simply clambers to the mouth when it wants a snack of upchuck. The tiny pest allows most of the sweet, sticky treasure to go to waste, and multiple "lice" may shorten the bee's lifespan like some sort of living, crawling bulimia.

Spider-eating flies

Jorge Allmeida

These hump-backed pinheads look harmlessly silly, but as larvae, the Acroceridae or "small headed flies" are killer parasitoids of fly-kind's classic enemies, the spiders. The roly-poly adults would probably get themselves caught if they went after a spider directly, but their highly active larvae are fully equipped to hunt one down on their own and will even ride the wind to disperse themselves, a tactic also employed by baby spiders themselves. Once it finds a juicy arachnid (usually a trap-door spider) the little maggot climbs a leg and usually bores right into the spider's body, though at least one species will first cut a tiny hole in the host's side and molt into an entirely new form, thin and soft enough to slip through. The larger form protects it on the quest for a host, while the thinner form can get inside without causing as much damage to its new home. When the time comes to pupate, it will finally kill the spider and consume what's left from the inside.

Thaumatoxena

"Variety of body forms in adult female Phoridae"

One of the least fly-like adult flies, the abdomen of a female Thaumatoxena is dominated by a single segment, her wings are pointed stubs and her head is a thin crescent, with eye-like sockets for her blunt antennae. Her simplified anatomy fits together in a smooth, durable "pill" scarcely larger than your average mite, and as you might have guessed if you've been paying attention, the degenerate form suits a highly specific lifestyle in close symbiosis with another creature; in this case, termites. Agriculturists may be pleased to know that insects put up with pests of their own, as these turtle-like flies live off the symbiotic fungus gardens of their hosts. The winged males were once mistaken for a separate species; their more conventional form allows them to travel from one termite nest to another.

"Variety of body forms in adult female Phoridae"

Less extreme but no less odd looking, the related Termitoxenia seem to secrete substances that termites find appetizing, and their reduced wings are even used as handles by the termites to carry them around.

The flightless females of another phorid bear some slight resemblance to the Termitoxenia, but these girls live in the oddest place of all; swimming in and feeding on the slime of the giant land snail, Achatina achatina. We know very little of their life cycle, except that males are winged and land on snails only to find a mate. Females and larvae are probably spread between snails by contact, or when one snail passes over the slime trail of another.

The Bot Flies

Charley Eisman

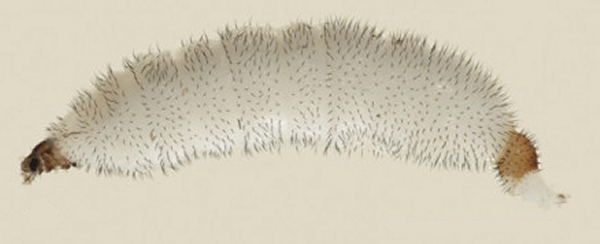

The much-maligned bot-flies have no mouths and cannot feed as plump, fuzzy adults, but spend their notorious larval stage buried in the still-living flesh of a vertebrate host. Different species prefer different mammals as incubators, but typically lay their eggs on other insects to make the delivery for them. Dermatobia hominis, the human botfly, stalks her host from a safe distance until she spies a hungry female mosquito. She wrestles her fellow dipteran in mid-air to lay dozens of tiny eggs on its abdomen, which will hatch when the mosquito lands on a warm human body...

Heavily barbed to resist easy extraction, each maggot may grow over an inch in length under the host's skin, spending its entire larval stage upside-down in a mucus-lined chamber, exposing only the tip of its snorkel-like tail to breathe. Fortunately, the larvae keep a fairly clean home - bacterial infections only seem to occur if the maggot dies - and will exit harmlessly when the time comes to pupate. Horror stories of these maggots embedded in the eye or vital organs are isolated, freak incidents, and the safest way to get rid of one is to simply let it run its course.

Other species of bot-fly are internal parasites. Gasterophilus lay their eggs on the fur or around the lips of grazing mammals such as horses and cattle; licked into the mouth by the host, the maggots bore into the tongue or gums until they grow larger and allow themselves to be swallowed. Their barbs and hooks anchor them to the walls of the digestive tract until they pupate, passing out of the body in feces.

The Screw-Worm Flies

Bot flies are weird, fascinating parasites and I'm inclined to find them a bit cooler, but I'm not sure how they've managed to earn quite so much infamy. Find any article on "horrifying" insects and bot flies are likely to top the list, with barely a mention of the screwworm flies. Sure, botfly maggots are a lot larger, but they don't normally cause any long-term harm to the host and certainly aren't lethal under any normal circumstances. Not so for screwworm maggots, whose vast numbers can maim or even kill hosts as large as full-grown cattle. Let's let that sink in a moment. Maggots that can eat a cow to death. Maggots that have eaten human beings to death. Maggots that could eat you to death.

Cochliomyia hominovorax means "spiral maggot man-eater," and was eradicated in the United States as of 1982 with more extermination programs active around the globe (bogleech.com does not endorse the genocide of terrifying animals). This species of blowfly (like the less dangerous bluebottles and greenbottles common around garbage) reproduces only in living tissue, laying over a thousand tiny eggs near any wound it can find on the host's body - even as small as a tick bite. Within twelve hours, the eggs hatch and the maggots begin to tunnel painfully through healthy flesh, creating a bigger, deeper wound that can immediately take on infection, necrotizing (ROTTING) and smelling even more attractive to flies - especially to more female screwworms, who can smell the ideal nursery miles downwind. Left untreated, wave after wave of maggots will hatch and feed in the same wound for as long as the host has living tissue to consume, which may not be long if the infections can't be treated.

...What?

How is that not cool?

You're weird.

New Zealand Bat Flies

Rod Morris

A species so unique it was given its own genus and family, Mystacinobia zelandica is a blind, wingless, long-limbed insect specially adapted to climb through the fur of Mystacina tuberculata, New Zealand's lesser short-tailed bat. By now, wingless symbiotic flies are probably getting old (welcome to bogleech.com!), but these guys are among those rare insects to be welcomed in a mammal's fur. Their bat roommates, who prey heavily on insects, pay no mind at all while these plump morsels scuttle all over their bodies. It's not blood the bugs are after, but nutrient-rich guano; the insects live entirely off residual feces they clean from the host fur. It's like one of those living hygiene products on The Flintstones.

Far more social than most other flies, Mystacinobia raise their eggs and young in communal nurseries near the roosts of their bat hosts. Females carefully groom one another and their larvae, while special males live beyond their usual lifespan, cease reproducing and become a sort of elder guardian caste, emitting a collective buzz which apparently tells bats to keep a safe distance from the nursery. An ingenious course of evolution for what amounts to bat toilet paper.

The Other Bat Flies

Jorge Almeida

While the New Zealand bat fly is a single species in its own distinct family, the Nycteribiidae are a family of several hundred "bat flies" completely unrelated to Mystacinobia. They may look like sisters on the outside, but they're scarcely second cousins, belonging to two different superfamilies of the three that form the Diptera. Unlike our gentle poo-eaters, these other guys are true blood-sucking parasites, and will never leave their bat host's body as adults. Unlike any other insects but the closely related louseflies, their larval stage completes its development still inside the mother's body, and she will lay pupa instead of eggs. If you're looking for the head in this monstrosity, it's the pointed, nearly featureless lump between the front legs.

Ant Larva Mimics

Source

Ants aren't off the hook yet, (not by a long shot. You'll see.) as we have yet another fly adapted to take advantage of social insect hospitality, and even a relative of the termite-loving weirdos at #9. What you're looking at here may resemble a maggot, but take a better look and you'll find the head and thorax of an adult fly. The "maggot" is merely the enormous abdomen of this wingless, even legless female phorid fly, and it perfectly imitates ant larvae of the genus Aenictus down to the all-important smell. These plump, lazy ladies end up carried, fed and fiercely protected by a roving horde of highly aggressive army ants, who ought to be more suspicious when some of their "larvae" are visited by tiny, flying males. They grow up so fast.

Stalk-eyed Flies

Source

If for some strange reason you're beginning to get tired of bloodthirsty parasites and predators, here's a family of cute little weirdos who wouldn't hurt a...different fly. Feeding on fungi, bacteria and decaying vegetation near bodies of water, the Diopsids or "stalk-eyed" flies are named for the bizarre head shape of the males, whose eyes and antennae are held apart on handlebar-like stems. Females are attracted to males with the widest eye-span, and competing males will face one another in comical waggling-matches to compare their stalk length, even inhaling air to bug their eyes out even farther. As female preference breeds males with ever longer stalks, males have a more difficult time actually flying; their exaggerated symbol of masculinity impairing their vision. Anything for the ladies.

Glowing Spider-Worms

New Zealand's Glow Worm Cave is hailed by scientists and tourists alike as one of the world's most beautiful living wonders, but the twinkling fairy-lights have a far from romantic source; they're the mucus strands of predatory fungus gnat maggots, illuminated by bacteria. No, not romantic...what's a better word for that? How about METAL?

Teejaybee

Dwelling in a hammock-like tube of slime, the transparent worm spins dozens of hanging silken threads and beads them with extremely sticky, sometimes even poisonous globules of mucus, illuminated by the waste product of symbiotic bacteria. As I explain arguably better on Cracked.com, the collective light show of these slimy bug-anglers effectively lures moths, mosquitoes and other night-flying insects right into their sticky snares, and may even fool such prey into seeing the starlit sky, preventing them from finding a way out of the deadly cave. Once it feels a tug on its fishing line, the maggot simply eats the entire strand, insect and all.

Though hardly in such spectacular concentration, different species of these killer lanterns can be found in a number of caves, canyons, dense forests and other dark, environments where the still air won't disturb their traps. Most are native to Australia, but a few inhabit North America, including a huge colony in Dismals Canyon, Alabama - carrying the awesome local nickname "Dismalites." The short-lived adult gnats can glow, but don't do so often and apparently don't need to. They are far from immune to the sticky traps of younger cousins, but lay more than enough eggs to compensate for the loss.

Ant-Decapitating Flies

Copyright Alex Wild

Pseudacteon are another genus of phorid fly which exclusively parasitizes ants, (what did I say? They have bigger fly problems than you do by far) especially the dreaded Solenopsis or "fire" ants. These invasive, aggressive, venomous ants are the terror of other insects and even many vertebrates, but fly into a futile panic when their antennae pick up the distinct buzzing of a single tiny Pseudacteon female.

Swooping down on the first worker she can catch, the mother fly inserts her needle-like ovipositor into an ant's thorax and lays a single egg in the blink of an eye. Once hatched, the maggot makes its way into the host's head, where it feeds on hemolymph, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. When it finally devours the last of the ant's brain, the host wanders aimlessly for up to two weeks until the parasite dissolves the connective tissues of its neck, causing the entire head to drop clean off. This will serve as a tough protective casing while the maggot pupates, and the adult will carefully saw its way out or squeeze through the former ant's mouth.