Everyone Should Love...

COCKROACHES

Written by Jonathan Wojcik

Source

As we speak, more than 4,500 documented species of Blattodea are scuttling around this little planet, products of a wildly successful evolutionary history stretching back at least 350,000,000 years. Trillions of them feed and multiply across every known land mass, and some have even persevered in the otherwise desolate, toxic wastelands of concrete, metal and glass erected by an equally widespread, mammalian biped.

Fortunately, these ubiquitous creatures are technically incapable of causing us any direct harm, lacking stingers, fangs, claws or any known parasitic adaptations, and our biosphere is left overall far healthier by their presence. Steadily consuming millions of tons of organic rubbish per day, they're part of a biological recycling system crucial to the continued health of every terrestrial habitat on the globe, and fulfill a wide variety of other ecological roles, from preying upon more destructive insects to pollinating an assortment of plant life.

Strange, then, that so many people would resent these animals for even being.

To many people, cockroaches are obnoxious, worthless "creepy crawlies" at best, nauseating nightmare fuel at worst. The pest control industry loves to remind us of the many pathogens they can allegedly smear around our personal space, generating billions of dollars a year just to poison them to death. To liken someone to a cockroach is to dismiss any measurable value in their very existence, making them a favorite symbol of spiteful political cartoons and hate-speech. They're villains and monsters in countless works of fiction, and played for at least minor gross-outs in countless others.

As far as most of us are concerned, the Blattodea's foremost claim to fame is nothing more than its audacious ability to multiply and thrive where we gave precisely no consent for any sort of "nature" to be multiplying and thriving, especially nature that can't even have the common decency to be dolphins, or red pandas, or something else more commonly "acceptable" in the eyes of us half-bald, oily-skinned apes. If there's one thing we can't stand, it's life that just keeps on living where we didn't even tell it, and if we can't turn a given species into either bacon or a hilarious internet meme, it's already on the fast track to vermin status.

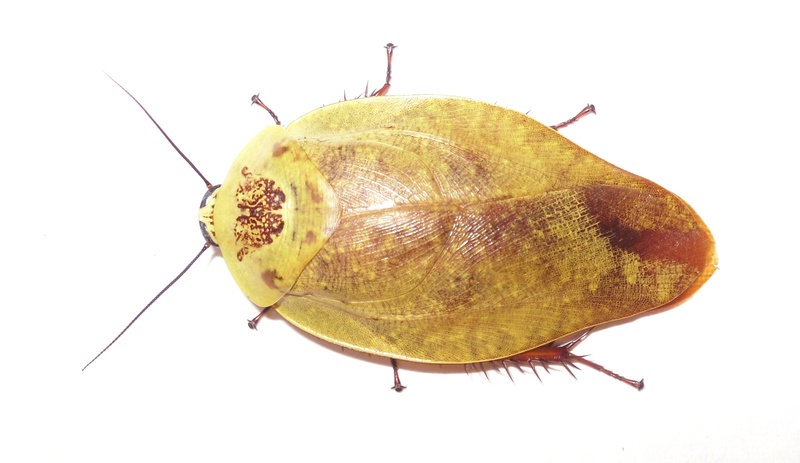

Ellipsidion humerale by Jean Hort

To generalize cockroaches as "pests," however, is rather like generalizing birds as flightless, arctic fish-eaters. Of those 4,500 some cockroaches we've catalogued, only a couple dozen, at best, have ever been known to establish themselves in human living quarters. Only four species do so with any sort of regularity, and of those four, just one species - the tiny "German" cockroach, Blattella germanica - is responsible for the majority of persistent "infestations." Most cockroaches, like most of the animal kingdom at large, simply aren't suited to raising a family in a fortress of linoleum and drywall, no more comfortable indoors than a butterfly or a grasshopper. Different species may favor sandy deserts, humid forests, grassy plains, rocky canyons, slimy bogs or musty bat caves, but an ape-house? With all that plastic and stuff? Harsh.

Granted, those weirdo-roaches who share our domestic tastes have really taken it to heart, following us everywhere we've gained a foothold and now far outnumbering many of their wild cousins, but even these city-dwelling deviants fall short of their repulsive reputation. Though traditionally viewed as filthy, garbage-loving germ factories, the presence of roaches in a home has little to do with its level of "cleanliness," as even the most sanitary dwelling offers enough glue, plaster, dust and mold to sustain your tiny roommates for uncountable generations. They certainly do appreciate rancid, festering trash, sure, but only because they appreciate basically whatever they can get; they're omnivorous opportunists, happy as long as they have access to something chewable and more or less organic in origin.

Source

Now, I'm not going to say that it's completely irrelevant to have tiny animals endlessly breeding, pooping and dying right where you cook your dinner. Cockroach waste has been known to trigger serious asthma attacks in a portion of the population, and any significant build-up of organic matter could eventually provide a substrate for unwanted microorganisms, but when it comes to contagious diseases, cockroaches are significantly less dangerous than the Orkin Man would have us believe.

No known human parasite or pathogen employs roaches as a natural vector, so unlike the Malaria-carrying mosquito or corpse-wallowing blowfly, the threat posed by a cockroach is only that posed by any member of your household who forgets to wash their hands: if it previously came into contact with something particularly unsanitary, a cockroach could, in theory, track microbial contaminants across your ham sandwich, potato salad, children or something else you intend to consume.

It's a danger that sounds almost inevitable when dealing with tens of thousands of the little scamps, but bear in mind, the scenario requires a little more than just cockroaches to play itself out. Think, for a moment, how often you actually leave food unattended long enough for a tiny animal to walk on it, and more importantly, how many sources of hazardous bacteria are actually close enough to said food for a tiny animal to walk across both of them during that unattended period. Do you keep your cat's litter box directly next to the refrigerator? Do you leave raw chicken juice drying in a sticky film by the sink for days? Do you wait to take out the garbage when you can smell it from the driveway?

It's the harsh truth that raid commercials are too polite to tell you: if cockroaches are tracking disease around your house, it's more than likely your disease. The roaches found those germs where you left them. You are the dirt. You are the vermin.

...And while contracting something like salmonella from a cockroach requires a highly specific sequence of events and significant sloppiness on your own part, any everyday shopping trip will put you in direct, repeated contact with an invisible cocktail of skin flakes, hair, sweat, sebacious oil, snot, saliva, urine and residual feces from thousands of fellow human beings, a significant portion of which were definitely, definitely carrying at least one of several thousand viruses, bacteria, fungi or parasites specifically adapted to spread wildly between members of our own kind. We humans are so pestilent, so slovenly, that we make cockroaches dirty by association. It's a good thing that bacteria just have such a harder time clinging to their slick, shiny exoskeletons than to the sticky, hairy, spongy surface of our own cracked and lumpy flesh.

Polyzosteria mitchelli from What's That Bug

In the days before soap, our ancestors were more than likely even safer with a den full of roaches than without, since their foraging habits would have continuously cut back on the growth of toxic mold, mildew, bacterial films and even a number of nasty ectoparasites. Roaches will readily devour most tinier insects or insect eggs, and have demonstrated a particularly hearty appetite for the dreaded bedbug, one of our most dastardly vampiric foes. Domestic cockroaches never evolved to undermine us larger beasts, but to live in a mutually beneficial symbiosis, putting our continuous generation of grime to good use.

Aptera fusca via Wikimedia Commons

So they're not just slavering, sewage-licking ghouls, and not half the biohazard of a Wal-Mart shopping cart, but beyond their overblown image, what else is there to cockroaches? They don't exactly spin webs, they don't spit acid, they don't lay eggs in caterpillars, they don't even go through any kind of metamorphosis; baby cockroaches come out already looking like cockroaches. When you get right down to it, they're sort of just the "everyman" arthropod, what the scientifically inclined would call "physiologically generalized." The go-to insect. The default bug.

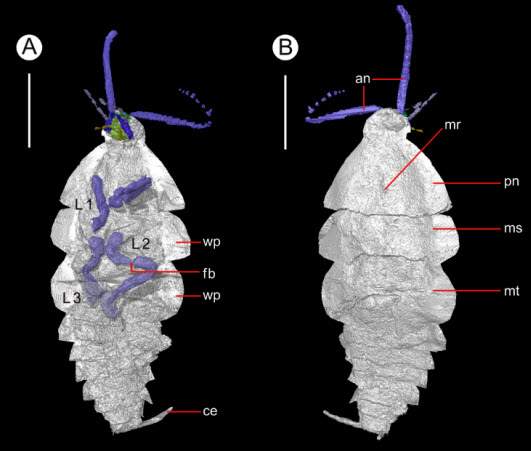

It's easy to think of cockroaches as almost boring compared to the weird diversity of the flies, beetles or wasps, but it's that same simplicity that has proven such a boon to their survival. This straight and narrow evolutionary course began all the way back in the carboniferous period, when ancient Blattoptera or "roachoids" roamed the foggy swamps of a younger world. Otherwise quite similar to modern roaches, these basal insects possessed long, sharp ovipositors for implanting their eggs in soil or wood, and despite what you might have expected, they averaged a bit smaller than cockroaches today. Several modern species are easily two to three times the size of their largest known fossil ancestors.

Frupus

Diversifying rapidly, roachoids would branch out by the end of the carboniferous into two closely related groups: the modern Blattodea we all known and love, and the more predatory, antisocial Mantodea, or preying mantises. One took the path of the lone, flamboyant serial killer, the other the path of the peaceful, communal scavenger, the dirt-farming peasants to Mantodea's fabulous samurai-dragons.

Pill Cockroach by Beetles in the Bush

This isn't to say that roaches don't get a little unusual from time to time. There are armor-plated species that can curl into tight spheres, semi-aquatic roaches that can submerge in water for extended periods of time, at least one species with cricket-like jumping legs, many roaches who can spray a defensive odor and a few species reported to glow under the right conditions, though none of these stray very far from the basic cockroach template, and that's precisely why they can boast such broader success than their ravenous, sickle-clawed sisters.

Jean Hort

Like a human rogue in Dungeons and Dragons, cockroaches have left themselves open to whatever life might throw at them, rarely settling too snugly into a limited niche. Whatever their preferences, most cockroach species are still flexible enough to withstand environmental fluctuations that would decimate more specialized organisms; a desert roach can usually get by just fine when thrust into cooler, damper conditions, and a cockroach from a lush rainforest might still eke out an adequate living on a dry, rocky cliffside.

Polyzosteria fulgens by Jean Hort

Further driving the longevity of these plucky pipsqueaks is their inclination to cooperate, with virtually all known roaches exhibiting some level of social organization. Most can recognize a select circle of brood mates on an individual basis, and will stick especially close to immediate family. Even those pernicious "pest" species form long-term companionships, repeatedly foraging for food with the same associates and suffering a sort of "depression" if isolated for too long.

By Ciaran Dunsdon

The famous Madagascan hissing cockroach, a popular exotic pet, demonstrates another level of culture not unlike the pack dynamics of some mammals. Sparring with their blunt "horns," males establish a hierarchy of dominance over one another, the top fighter usually fathering the largest number of offspring. Female preferences aren't always so predictable, however; some seem actively turned off by the larger, more aggressive males, and may favor the exiled losers or "non-combatives" who sulk around the swarm's outer edges. Aptly named, these roaches also emit a range of different hisses proven to convey different meanings among packmates - cockroaches with words!

Other cockroach species may prefer a quieter, more domestic life, forming monogamous pairs who work together rearing a single clutch of young. In Macropanesthia rhinoceros, one of the largest and longest-lived of all roaches, babies may remain with their parents in the same burrow until they're over three years old. Many young roaches depend upon their parents to pre-chew their food, and some even "nurse" on nutritious secretions directly from their mother's body. In members of the genus Thorax, the mother will carry her little ones under specially fused wing covers; little ones whose unusual, temporary "fangs" allow them to slice open her back and drink minute amounts of her haemolymph, or "blood."

Alex Wild

In any case, cockroach socialism usually falls somewhere directly between a semi-solitary lifestyle and an organized "colony," but the class Insecta isn't one to half-ass anything for long, and one divergent group of roaches are so heavily modified for community living, we didn't even realize they were roaches until nearly 2008, after exhaustive genetic sequencing proved that the former order Isoptera, otherwise known as termites, were never anything more than an incredibly weird family of Blattodea.

Alex Wild

Like their fellow roaches, termites suffer their own set of negative stereotypes, most infamous for the destructive rate at which several species can devour wood, which oily-skinned ape-beasts are always trying to use as nesting material. It's hardly their fault that we keep trying to live in big piles of food, really, especially considering that old, dead wood is normally nothing but a fire hazard and fungus factory under natural circumstances. It's garbage. It's tree carrion. Termites exist to get rid of that nasty old rubbish, and without them, many forests would be suffocating under the weight of their own dead. Between the mantids and the termites, we can owe quite a bit of waste management and even outdoor pest control to the same convenient superfamily.

Synonymous with plague, squalor and ugliness throughout human culture, roaches have been more feared and demonized than some of the deadliest of predators and parasites, but however inconveniencing it may be for small creatures to poop into your toaster, Mother Nature never really intended these humble beings to make our enemies list. They're just so many tiny, fastidious overnight janitors, scrambling in the shadows to pick up after a world of greasy, sloppy giants who, against all evolutionary sense, are incredibly offended and disturbed by the free service. You're just lucky they lack the capacity to comprehend or care what you think, or you'd really be in trouble.

By now, maybe some of you have developed a whole new appreciation for these ancient animals, and maybe you're even thinking they might be kind of neat to have around the house, at least on your own terms. Lucky for you, the deliberate, captive care and feeding of cockroaches is actually a well established, widely enjoyed hobby with a wealth of online resources. Easier to care for than the average houseplant, equally as safe and several times more active, exotic roaches are a pet I'd recommend to anyone who wants some sort of little life-form puttering around an aquarium. Soil, leaves and rotten wood are enough to keep many species happy indefinitely, and their population growth effectively regulates itself according to available food and space.

If you live in the U.S, Roachcrossing is by far the best supplier currently operating, with the widest selection of species shipped straight to your door! Other major suppliers include DoubleD's, Ken the Bug Guy and Bugs in Cyberspace, where you can even adopt a species extinct from its native range.

Go ahead...invite some roaches into your life. It's the least you can do for how the other sweaty monkeys have been conducting themselves.