| The Alien Lives of Parasites: Part One |

Degenerate. Lowly. Primitive. These are terms which, to many people, are immediately

brought to mind by the word "parasite." Even science was once guilty of labeling

parasitic life as a sort of "de-volution," a slothful step back for creatures that couldn't cut it

on their own. Little did we realize, survival in the body of another creature entails extreme

adaptation which, more often than not, surpasses the sophistication and craftiness of any

"free living" life-form.

brought to mind by the word "parasite." Even science was once guilty of labeling

parasitic life as a sort of "de-volution," a slothful step back for creatures that couldn't cut it

on their own. Little did we realize, survival in the body of another creature entails extreme

adaptation which, more often than not, surpasses the sophistication and craftiness of any

"free living" life-form.

As you read this, every macroscopic animal

on this planet is harboring at least one

species of parasite in or on its body,

including yourself. With more discovered year

after year, parasitic species may easily

outnumber the non-parasitic, and their

tremendous importance to the ecosystem

becomes more apparent the more they are

observed.

Parasites have an influence on which

animals are preyed upon, which animals

mate and which animals evolve. There is

even strong evidence that a some or all

human behavior - our tastes in the opposite

sex, our sleeping habits, our every mental

quirk - is subtly manipulated by the

microorganisms that invade our bodies.

on this planet is harboring at least one

species of parasite in or on its body,

including yourself. With more discovered year

after year, parasitic species may easily

outnumber the non-parasitic, and their

tremendous importance to the ecosystem

becomes more apparent the more they are

observed.

Parasites have an influence on which

animals are preyed upon, which animals

mate and which animals evolve. There is

even strong evidence that a some or all

human behavior - our tastes in the opposite

sex, our sleeping habits, our every mental

quirk - is subtly manipulated by the

microorganisms that invade our bodies.

In part one of this article, I'll be detailing my three choices for the most bizarre, most

amazing parasites you may have ever heard of. I know you're excited. Let's start off with

an old favorite...

amazing parasites you may have ever heard of. I know you're excited. Let's start off with

an old favorite...

| -LEUCOCHLORIDIUM PARADOXUM- |

Imagine, if you will, the everyday life of a garden snail. Primarily nocturnal, you

avoid the dessicating rays of the sun as you slither in the shadows under dense

foliage, eating anything chewable you find in your slimy path. One day, you catch a

whiff of fresh bird droppings; to you, a delicious and nutritious meal. Days later,

however, you start to feel strange - at least as strange as your incredible simple

nervous system can muster - and against all logic, you feel attracted to the hot,

bright daylight your kind has spent millions of years hiding from. You go about your

snaily business as you always would, but this time, you're completely exposed, both

to the sun and to the eyes of hungry birds. Your foul tasting slime has taught most

avians that snails are an unappetizing meal, but unfortunately for you, you no longer

look like a normal snail.

avoid the dessicating rays of the sun as you slither in the shadows under dense

foliage, eating anything chewable you find in your slimy path. One day, you catch a

whiff of fresh bird droppings; to you, a delicious and nutritious meal. Days later,

however, you start to feel strange - at least as strange as your incredible simple

nervous system can muster - and against all logic, you feel attracted to the hot,

bright daylight your kind has spent millions of years hiding from. You go about your

snaily business as you always would, but this time, you're completely exposed, both

to the sun and to the eyes of hungry birds. Your foul tasting slime has taught most

avians that snails are an unappetizing meal, but unfortunately for you, you no longer

look like a normal snail.

Those droppings you ate were swarming with the eggs of the parasitic nematode,

Leucochloridium. Invading your simple little snaily brain, the worms have completely

rewired your behavior, and with their colorful, pulsing "brood sacs" crammed into

your eye-stalks, your head now resembles a couple of fat, juicy insect larvae - every

bird's favorite.

Leucochloridium. Invading your simple little snaily brain, the worms have completely

rewired your behavior, and with their colorful, pulsing "brood sacs" crammed into

your eye-stalks, your head now resembles a couple of fat, juicy insect larvae - every

bird's favorite.

You'll likely survive your eyestalks being ripped off, and eventually, your entire face

will grow back...as will the parasites. You're lucky evolution never granted you the

intellect to comprehend your new existence, enslaved by a worm in your brain to

have your eyes chewed off again and again.

will grow back...as will the parasites. You're lucky evolution never granted you the

intellect to comprehend your new existence, enslaved by a worm in your brain to

have your eyes chewed off again and again.

| -SACCULINA- |

The "insects" of the sea, Crustaceans come in all manner of curious shapes and

sizes, adapted to a wide array of aquatic environments. Few are so unusual as the

largely sedentary Cirripedia, more commonly known as the barnacles, and there is

surely no barnacle more unusual than genus Sacculina. Like the other Cirripedes, it

begins its life as a microscopic, free-swimming "nauplius," but rather than anchor in

place and feed on plankton for the rest of its life, a female Sacculina spend its youth

hunting for one of its fellow Crustacea; a crab several thousand times its own size.

sizes, adapted to a wide array of aquatic environments. Few are so unusual as the

largely sedentary Cirripedia, more commonly known as the barnacles, and there is

surely no barnacle more unusual than genus Sacculina. Like the other Cirripedes, it

begins its life as a microscopic, free-swimming "nauplius," but rather than anchor in

place and feed on plankton for the rest of its life, a female Sacculina spend its youth

hunting for one of its fellow Crustacea; a crab several thousand times its own size.

Once Sacculina locates a suitable host, it inserts a thin needle into a seam in the

crab's armor, injects its own cells into the host and discards the rest of its own

body. Now little more than a protoplasmic blob, it begins to grow through the crab

like a tumor, wrapping fungus-like tendrils around organs, muscles and even the

crab's eyes.

crab's armor, injects its own cells into the host and discards the rest of its own

body. Now little more than a protoplasmic blob, it begins to grow through the crab

like a tumor, wrapping fungus-like tendrils around organs, muscles and even the

crab's eyes.

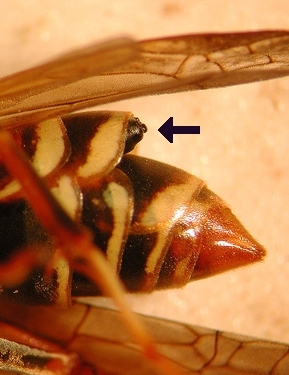

Soon, the intruder reveals its presence to the outer world as a bulging, blobby body

known as the externa, located where the host crab would normally carry a sac of

eggs. If the host happens to be male, the parasite simply alters its hormonal balance,

adjusting the crab's body and behavior to resemble that of an egg-carrying female.

known as the externa, located where the host crab would normally carry a sac of

eggs. If the host happens to be male, the parasite simply alters its hormonal balance,

adjusting the crab's body and behavior to resemble that of an egg-carrying female.

It is at this point that the male Sacculina finally enters the picture: Injecting itself into

the externa, it fertilizes the parasite's eggs, and the crab is induced to nurture them

as it would its own. Eventually, it will climb atop a rock or coral and shake its body in

the current, an action that would normally release thousands of crab larvae into the

surrounding water. The crab can never reproduce with its own kind, only continue to

raise the offspring of a cancerous invader.

the externa, it fertilizes the parasite's eggs, and the crab is induced to nurture them

as it would its own. Eventually, it will climb atop a rock or coral and shake its body in

the current, an action that would normally release thousands of crab larvae into the

surrounding water. The crab can never reproduce with its own kind, only continue to

raise the offspring of a cancerous invader.

| -The Strepsiptera- |

"Strepsiptera" translates as "twisted wing;" and wings aren't the only thing twisted

about this order of Insecta. As spiny, hopping larvae, they will either lie in ambush or

actively hunt for another insect to parasitize, with roughly 600 known species

specializing in different hosts including bees, beetles, cockroaches and even

silverfish. Once a larva locates its preferred target, it secretes a corrosive enzyme to

melt its way into the other insect's body, loses its legs and creates a protective

chamber out of the host's own tissues. If the parasite is female, this is how it shall

remain for the remainder of its existence.

about this order of Insecta. As spiny, hopping larvae, they will either lie in ambush or

actively hunt for another insect to parasitize, with roughly 600 known species

specializing in different hosts including bees, beetles, cockroaches and even

silverfish. Once a larva locates its preferred target, it secretes a corrosive enzyme to

melt its way into the other insect's body, loses its legs and creates a protective

chamber out of the host's own tissues. If the parasite is female, this is how it shall

remain for the remainder of its existence.

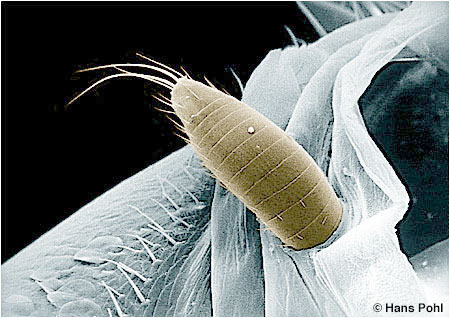

The mature female is easy to identify once you know where to look, as her head

protrudes noticeably from the exoskeleton of her host. It is through this end of her

body that she performs all reproductive functions, releasing a mating pheremone,

copulating, and depositing live larva all through an orifice in her face. Our species

can only imagine how it feels for a small, flying male to chase you down and have sex

with the head sticking out of your back, so remember to thank whatever merciful

creator you believe in that you weren't born a wasp.

Nor a crab.

Nor a snail.

protrudes noticeably from the exoskeleton of her host. It is through this end of her

body that she performs all reproductive functions, releasing a mating pheremone,

copulating, and depositing live larva all through an orifice in her face. Our species

can only imagine how it feels for a small, flying male to chase you down and have sex

with the head sticking out of your back, so remember to thank whatever merciful

creator you believe in that you weren't born a wasp.

Nor a crab.

Nor a snail.

If we're dealing with a male Strepsiptera, our parasite will eventually undergo

metamorphosis into the order's namesake, a delicate little insect with unusual

fan-like wings and even more unusual eyes, whose structure is partially shared only

by the long-extinct Trilobita. With a lifespan of only a few hours, the male is

unequipped to even feed at all, with his mouthparts modified into an array of sensory

appendages.

metamorphosis into the order's namesake, a delicate little insect with unusual

fan-like wings and even more unusual eyes, whose structure is partially shared only

by the long-extinct Trilobita. With a lifespan of only a few hours, the male is

unequipped to even feed at all, with his mouthparts modified into an array of sensory

appendages.