| Seven of the World's Weirdest Plants |

| Written by Jonathan C. Wojcik - Photo credits unknown or from public news articles unless otherwise noted. If you know their sources and need them credited or removed, please e-mail me. |

Everyone should be familiar with the genus Dionea or "Venus Fly Trap" above, but the vegetative

world is home to plenty stranger, and while perhaps not as adrenaline-pumping as Crustaceans

or as gruesome as Amphibians, plants provide food, shelter and oxygen for the entire kingdom

Animalia, so they certainly deserve the spotlight once in a while, and their weirdness does not

disappoint.

world is home to plenty stranger, and while perhaps not as adrenaline-pumping as Crustaceans

or as gruesome as Amphibians, plants provide food, shelter and oxygen for the entire kingdom

Animalia, so they certainly deserve the spotlight once in a while, and their weirdness does not

disappoint.

| Bladderwort Traps |

Rather unremarkable in appearance from above, these tiny aquatic plants are actually

carnivorous, and display one of the most sophisticated mechanisms (carnivorous or

otherwise) in the entire known plant kingdom.

carnivorous, and display one of the most sophisticated mechanisms (carnivorous or

otherwise) in the entire known plant kingdom.

| Photos by Thomas Lendl and Barry Rice |

The "bladders" of the plant's namesake are thousands of tiny, sac-like pods which hang

from submerged branches, each equipped with a hinged "door" and membranous seal

held shut by a delicate equilibrium of pressure. At the slightest touch by some tiny insect,

crustacean or even protozoa, the seal is broken and the bladder floods with water,

sucking in the prey for digestion.

from submerged branches, each equipped with a hinged "door" and membranous seal

held shut by a delicate equilibrium of pressure. At the slightest touch by some tiny insect,

crustacean or even protozoa, the seal is broken and the bladder floods with water,

sucking in the prey for digestion.

| Un-carnivorous Plants |

Members of the genus Nepenthes are usually adapted to attract, trap and digest insect

prey in their fluid-filled "pitchers," but Nepenthes lowii favors an alternative, even less

savory diet. The rim of its "trap" secretes a sweet, milky substance that small birds may

find both an enticing treat and fast-acting laxative; only seldomly catching insects, lowii

derives most of its sustenance as a public toilet.

prey in their fluid-filled "pitchers," but Nepenthes lowii favors an alternative, even less

savory diet. The rim of its "trap" secretes a sweet, milky substance that small birds may

find both an enticing treat and fast-acting laxative; only seldomly catching insects, lowii

derives most of its sustenance as a public toilet.

Another un-carnivorous pitcher is Nepenthes ampullaria. While other pitcher traps are

shaped to keep clear of fallen leaves, twigs and other inedible detritus, this scavenging

cannibal leaves itself open to whatever might fall into its gaping gullet, actually favoring the

digestion of vegetable matter.

shaped to keep clear of fallen leaves, twigs and other inedible detritus, this scavenging

cannibal leaves itself open to whatever might fall into its gaping gullet, actually favoring the

digestion of vegetable matter.

| "Sexual Deception" in Orchid Flowers |

At first glance, the flowers of many orchid species can fool even a human into seeing

some colorful bee, fly or wasp, and the resemblance is far from coincidence. Each flower

not only approximates the size, shape and color of a different local insect, but imitates the

female reproductive pheromones of the appropriate species, attracting male insects in a

certain special mood.

some colorful bee, fly or wasp, and the resemblance is far from coincidence. Each flower

not only approximates the size, shape and color of a different local insect, but imitates the

female reproductive pheromones of the appropriate species, attracting male insects in a

certain special mood.

Whereas other flowers promise food to attract pollinators, orchids such as these take

advantage of insect mating signals to avoid the costly process of nectar production. As

the insects attempt to reproduce with the imposters, their bodies carry pollen from one

sneaky plant to the next.

advantage of insect mating signals to avoid the costly process of nectar production. As

the insects attempt to reproduce with the imposters, their bodies carry pollen from one

sneaky plant to the next.

| A Predatory team-up |

Though adapted to attract and trap insects in its sticky coating, the "paracarnivorous"

Roridula genus produces no digestive enzymes of its own, leaving the final act of

predation in the hands of a second party...

Roridula genus produces no digestive enzymes of its own, leaving the final act of

predation in the hands of a second party...

Spending their entire lives on the foliage of Roridula, the assassin bugs Pameridea

roridulae and Pameridea marlothii prey exclusively on other insects trapped by their host

plant, which in turn derives nourishment as the predators defecate. This makes Roridula

the only known plant genus that provides food for a carnivore in order to farm its own

fertilizer.

roridulae and Pameridea marlothii prey exclusively on other insects trapped by their host

plant, which in turn derives nourishment as the predators defecate. This makes Roridula

the only known plant genus that provides food for a carnivore in order to farm its own

fertilizer.

| The Parasitic Corpse Flower |

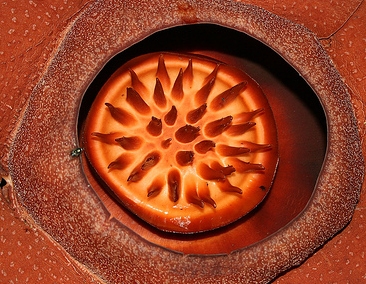

Over a meter across, the flower of this rare Malaysian plant is the single largest known to

man, and that's only the beginning of Rafflesia arnoldii's unusual characteristics. The rest

of the plant consists only of a fungus-like filament, which grows as a parasite exclusively

within the vines of Tetrastigma, an exotic relative of the grape. Arnoldii produces its

titanic bud directly from the surface of its host, and grows for several months to bloom for

only a few days.

man, and that's only the beginning of Rafflesia arnoldii's unusual characteristics. The rest

of the plant consists only of a fungus-like filament, which grows as a parasite exclusively

within the vines of Tetrastigma, an exotic relative of the grape. Arnoldii produces its

titanic bud directly from the surface of its host, and grows for several months to bloom for

only a few days.

Often called a "corpse flower," the odor of this monstrous blossom is notoriously

unpleasant, imitating the decaying flesh of a dead animal. Its hairy, leathery texture and

reddish coloration contribute to this illusion, attracting flies and other scavengers for

pollination. It is not known exactly how its seeds reach other Tetrastigma, but they may

stick to the fur of passing rodents. Amazingly, only one will be produced from each flower.

unpleasant, imitating the decaying flesh of a dead animal. Its hairy, leathery texture and

reddish coloration contribute to this illusion, attracting flies and other scavengers for

pollination. It is not known exactly how its seeds reach other Tetrastigma, but they may

stick to the fur of passing rodents. Amazingly, only one will be produced from each flower.

Most trees and shrubs in the Acacia genus discourage hungry herbivores with a bitter

alkaloid chemical in their tiny leaves, but a few species have developed an even more

effective and far more amazing line of defense by forming a mutual partnership

(symbiosis) with biting, stinging ants. One such partnership is demonstrated by the

Acacia cornigera or "bullhorn" acacia and the ant Pseudomyrmex ferruginea. The

large, hollow pods of the plant's namesake are a perfect place for the ants to raise

their young, and the plant produces two kinds of sustenance especially for its tenants;

carbohydrate-laden nectar from glands along its stalks and nodules of protein from the

tips of its leaves. In return, the ants not only attack other animals that disturb their home

but clear away any other vegetation that may grow around the base of the tree.

alkaloid chemical in their tiny leaves, but a few species have developed an even more

effective and far more amazing line of defense by forming a mutual partnership

(symbiosis) with biting, stinging ants. One such partnership is demonstrated by the

Acacia cornigera or "bullhorn" acacia and the ant Pseudomyrmex ferruginea. The

large, hollow pods of the plant's namesake are a perfect place for the ants to raise

their young, and the plant produces two kinds of sustenance especially for its tenants;

carbohydrate-laden nectar from glands along its stalks and nodules of protein from the

tips of its leaves. In return, the ants not only attack other animals that disturb their home

but clear away any other vegetation that may grow around the base of the tree.

| Ants in the Plants |

| Dung Beetle Jail |

Hydnora africana is a plant that spends most of its existence completely underground,

feeding parasitically off the roots of more conventional flowering plants in the Spurge

family. The parasite reveals itself only when its bizarre, fleshy flowers begin to poke up

through the soil, emitting the smell of fresh, steamy feces. With their joined petals and

thick, inward-pointing hairs, the flowers are structured so that dung beetles and other

scavenging insects can easily enter, but cannot escape until the flowers are mature,

ensuring their prisoners will be thoroughly coated in pollen by the time they leave.

feeding parasitically off the roots of more conventional flowering plants in the Spurge

family. The parasite reveals itself only when its bizarre, fleshy flowers begin to poke up

through the soil, emitting the smell of fresh, steamy feces. With their joined petals and

thick, inward-pointing hairs, the flowers are structured so that dung beetles and other

scavenging insects can easily enter, but cannot escape until the flowers are mature,

ensuring their prisoners will be thoroughly coated in pollen by the time they leave.