By Jonathan Wojcik

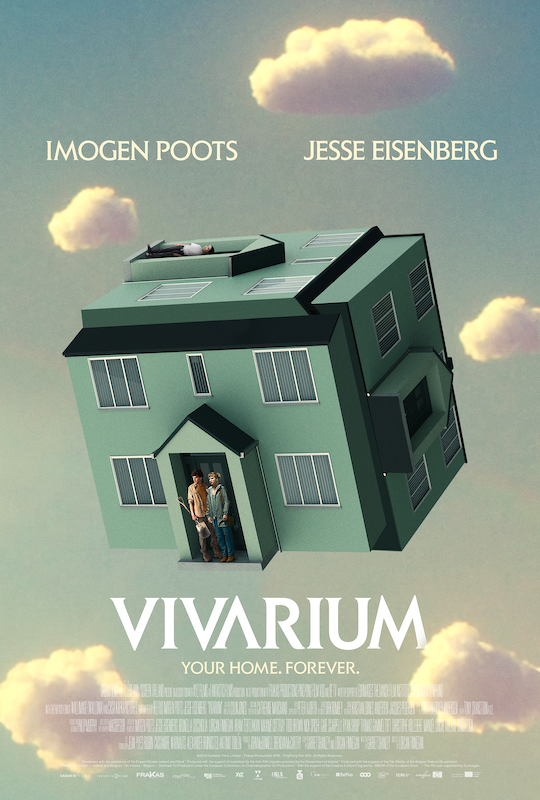

ENTRY 03: VIVARIUM

Today we look at 2019's

Vivarium, directed by Lorcan Finnegan from a screenplay by Garret Shanley, the two of them working together on the final writing! Even if you go in blind, you can guess exactly what this movie is about and probably predict its outcome from the clips that play over its opening credits, assuming you know exactly what it is you're looking at.

...But if you DO know the life cycle of a cuckoo when you see one, you're probably intrigued by the promise of a sci-fi horror film drawing any inspiration from

brood parasitism. Haha, just look at that rotten little shit! GET DUNKED you inferior host-species progeny!!! Hey, did you know

road runners are a kind of cuckoo? That has nothing to do with this movie, I just wanted you to know.

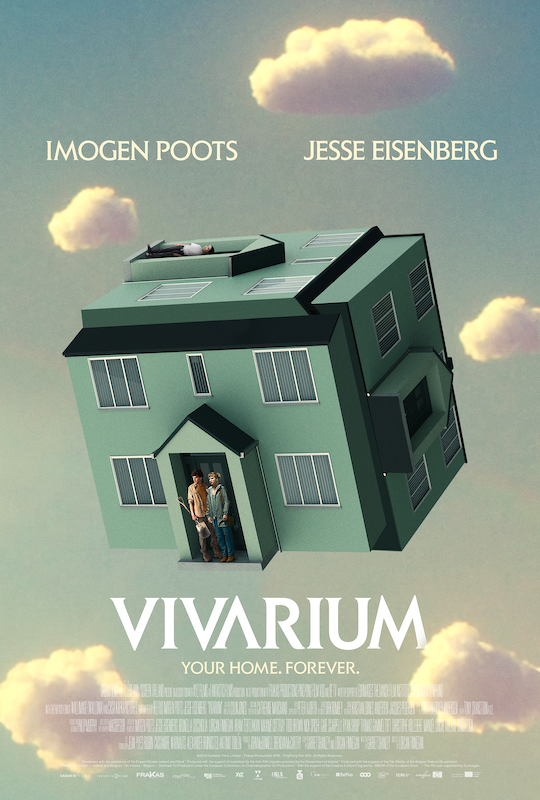

Vivarium stars Imogen Gay Poots as a schoolteacher named Gemma and the less memorably named (sorry dude) Jesse Eisenberg as her boyfriend, Tom, who finally want to settle down and find a dream home suitable for a hypothetical, future family. By terrible, terrible luck, their hunt takes them to the tiny real estate office of an agent known only as "Martin," who represents a housing development called

Yonder. Actor Jonathan Aris gives a great performance here as a man who's just a little too friendly and too "normal" for comfort, awkwardly nonthreatening in that forced, scripted customer service sort of way, a bit "off" in his understanding of small talk and with a subtle, uncomfortable sense of desperation through his disarmingly polite facade.

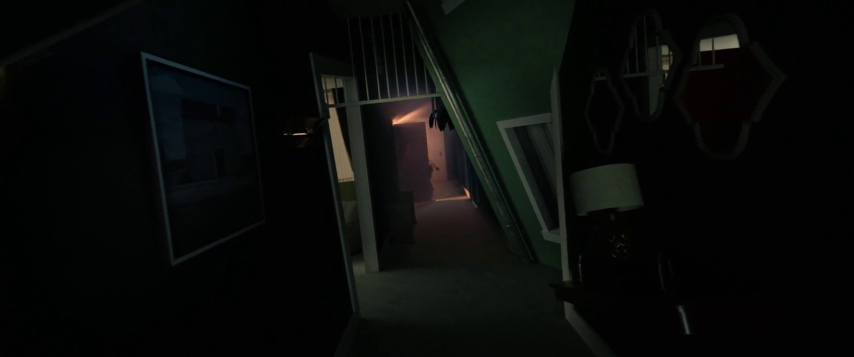

Following Martin to Yonder, the couple find an eerily sterile suburb of flawlessly identical, blocky green homes, where even the sky is filled with weirdly picture-perfect little poofy white clouds. They aren't quite sure it's the type of place they want to live, but they're willing to consider it enough to look around inside.

While the couple scopes out the tiny, bland back yard, Martin and even his car seem to vanish without a trace. It's strange and a bit rude, but not yet alarming. Not until they try to drive home, and no matter where they turn, "Yonder" never seems to end. They only keep finding themselves back in front of the same house, #9, still left unlocked for them. Their phones can't find a signal, there's nothing in the house that they can use to contact anyone, and their search for a route out of the hideous carbon copy nightmare only results in an empty tank of gas...again in front of "their" new home. Despite having never never seen another soul, let alone another vehicle, there's even a fresh delivery of generic, vacuum-packed food waiting for them on #9's doorstep.

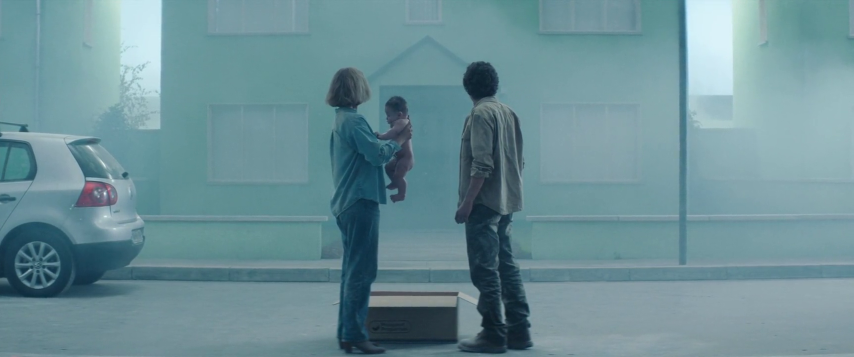

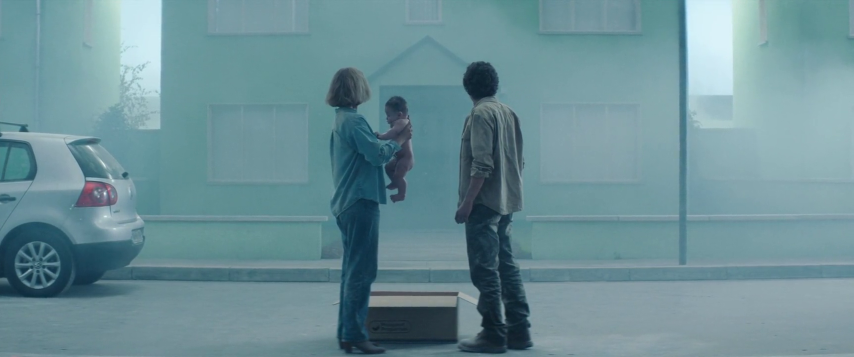

Desperate to attract any attention, they decide to burn the house down, but nobody comes, and they eventually awaken to find the house not only completely restored, but with an even more alarming new delivery.

The cardboard shipping box contains what appears to be a human infant, still wet and slimy, with a note that implores them to "raise the child and be released." With no known escape route, they submit to the request and settle into the house as best they can.

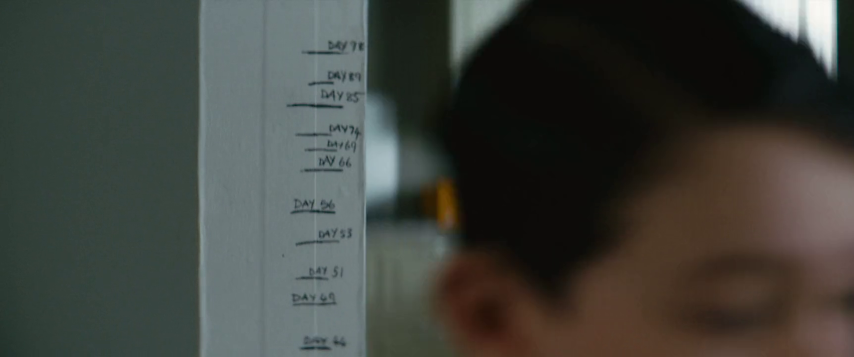

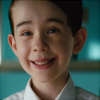

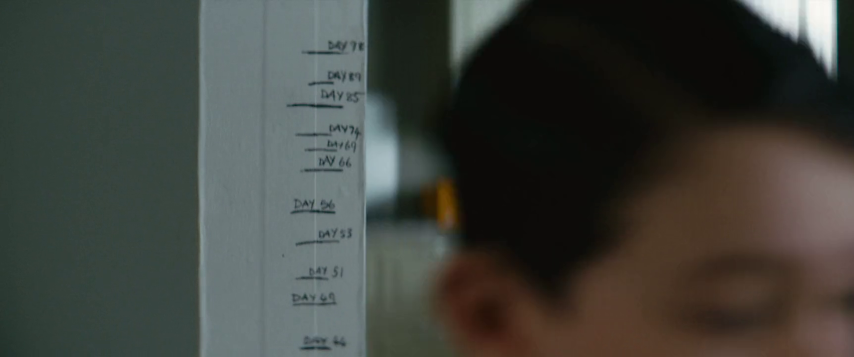

By our very next scene, the child has already grown to what looks roughly nine or ten years old, but Gemma and Tom haven't changed much in the mere two or three months that have really elapsed. Played by Senan Jennings, the boy is the spitting image of a much younger Martin, and Jennings is even more impressive in the role of something that

believes its human camouflage is convincing. Have you ever been reading a book in which a pre-teen character is supposed to be realistically childish and sympathetically innocent, but you can kind of tell the author hasn't interacted with real kids since their own adolescence at least forty or fifty years prior? It's almost uncanny how well this actor (and the script) ends up recreating that mood.

Mini Martin is an almost robotically "perfect" son in many ways. Always polite, cheerful and obedient, except for the

hideous (and involuntary?) alarm screech he emits every mealtime and other, subtler "alien" behavior. He practices mimicking the mannerisms of his human foster parents at every opportunity and can even distort his voice. Every day, he watches incomprehensible patterns on a television that receives no other known broadcast. He doesn't respond any differently to affection or mistreatment, he doesn't exhibit imagination, curiosity or wonder and he doesn't even make the constant, hilarious mistakes of logic or communication associated with growing up.

Yes, I know that some of this sounds eerily like the complaints of heartless "Autism moms" who think their children are "broken" if they don't laugh or cry or play with toys the "right way," but trust me, this is not a movie making a monster out of neurodivergence. We'll talk more about this shortly.

As they days go by, the child begins to drive an unintentional wedge between Gemma and Tom. Gemma still trusts that they may be released when they complete their purpose, and does her best to play the role of a parent. In the process, she begins to develop some genuine parental affection for the entity, and there are moments where it appears to truly appreciate her back. There's even a touching moment when the parents manage to get music playing in the broken-down car, and the child shows obviously genuine delight jumping and dancing around with them. Gemma feels jerked back to the reality of their situation only when the child shows no reaction at all to Tom slipping and hurting himself.

Tom, conversely, has only kept focus on escape, and having exhausted every other option, he becomes obsessed with

digging, hell-bent on finding out what's beneath this clearly artificial community. His obsession with his dirt hole becomes almost darkly hilarious, and it's not the most illogical idea, but he drifts even farther from Gemma as he begins to basically live out of the burrow, and farther still when he attempts to lock the boy in their car and starve him.

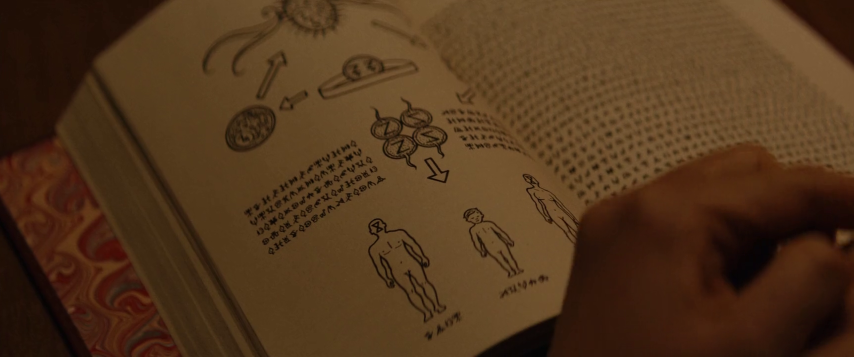

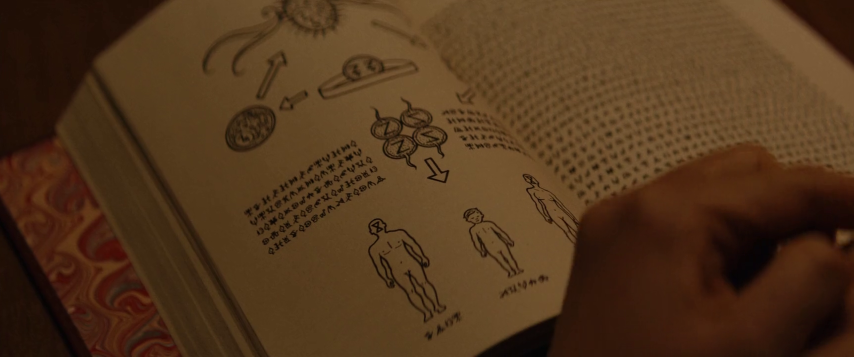

At one point, the boy disappears for the day and returns with a book. He won't (or can't?) tell Gemma where he went or who gave it to him, but inside she finds writing in an unknown language and scientific diagrams of only

near-human physiology. In a subsequent conversation with the child, she realizes how well he can imitate sounds, voices or behaviors and tries to use it to her advantage, praising his talent and challenging him to imitate herself and Tom. It's another near-wholesome moment as Gemma and the boy both get into the fun of this little game between them, until Gemma asks if he can imitate

anyone else he's met. Anyone at all that he might have encountered since his birth.

At this prompt, the boy hunches over, rolls back his eyeballs and begins to produce a croaking, trilling call as his throat inflates into a pair of frog-like vocal sacs. The truly inhuman display so terrifies Gemma that she never again shows the creature any form of tenderness or empathy, coldly obeying his alarm cries to keep him fed and very little else. Their lives become a mindless routine, Gemma performing the bare minimum to complete the childcare assignment and Tom going all-in on the life of a moleman.

Soon enough, the child has nearly reached maturity and both adults keep as distant from him as they can. He leaves almost daily, but Gemma is unable to figure out where he goes. Meanwhile, Tom's health has severely deteriorated by the time he digs deep enough to find anything other than soil: a pair of human corpses in plastic body bags. Their "son" finally locks them out of the house, forcing them to sleep in the car as Gemma begs him to get help for her husband.

The pseudohuman agrees it may be time for Tom to be "released," but we only learn what "release" may have always truly meant when he produces another of those same body bags to collect the now expired Tom.

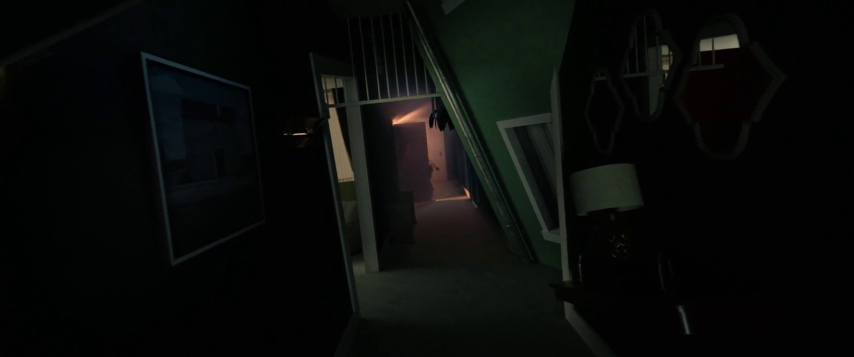

Finally pushed too far, Gemma snaps and attempts to kill the cuckoo-person with a pickaxe. She at long last finds out how he's been vanishing every day when he scurries off (on all fours, of course) and pulls up the solid concrete-like sidewalk as easily as a layer of carpet. Gemma just manages to wedge the impossible gap open with her pickaxe and follow after him, finding only a psychedelic distortion of their own generic Yonder household.

Gemma keeps sinking and shifting through this warped extradimensional space, catching glimpses of other Yonder households. Whether these are snippets of the past or concurrent with her own plight is unknown to the viewer; one haggard foster mother almost seems to notice the intrusion, but does nothing as Gemma is sucked through the morphing walls and floors. She sees a man who's killed himself in one of the bathrooms, and she sees a crazed, filth-caked couple having wild sex as their foster child creature observes and applauds. All things considered, Gemma and Tom seem like they've been doing an above-average job with theirs.

Unfortunately, it doesn't seem to be a journey the human body is equipped to withstand, as Gemma is deposited back "home" in a pained and helplessly weakened state. The thing she had worked so hard to help raise impersonally seals her up into the next waiting body bag as he cleans up the house, still addressing her as his mother but hardly blinking when her final, dying words to him are that she's

not his "fucking" mother.

We return to the real estate office in the final moments of the film, where the original "Martin" has already reached the end of his life cycle. His replacement takes the nametag for himself, bags up his predecessor, marks down some information, deposits the body down a chute, and nonchalantly sits down to await the next set of customers.

MONSTER ANALYSIS: MARTIN

From what we know, Martin's species is frightening in a number of ways; they clearly have access to advanced science and technology unknown to us, they live off our society without us knowing they exist, and they show no empathy or remorse towards the human lives that they use for their own benefit. None of these elements are new to horror in any possible combination, obviously, but they're most commonly applied to something more predatory, more powerful and much more malevolent. A secret society of vampires, an unseen realm of demons, a conspiracy of alien invaders.

Martin's kind are none of the above. There is no evidence that they work toward some grander doomsday uprising, that they meddle in the affairs of our civilization or that they intend any harm to us at all. They regrettably require human surrogates to nurture and acclimate them through the developmental phase of a pitifully ephemeral life cycle, and though they can't understand or relate to our emotions, they still make a clear attempt to keep their hosts comfortable. In fact, they go to some

pretty extreme ends to provide their "parents" everything they believe humans want out of life, and you get the impression that they're quite simply

not capable of comprehending the average host's negative response to it all. I never even got an impression that the foster parents are necessarily intended to die, even if it is for some reason an inevitability or common enough to be expected. The impression I get is that these creatures are surviving the only way they can, minimizing their effect on humanity and otherwise living among us as peacefully as possible, an interpretation I'm happy to say was all but confirmed in a

director interview loaded with compelling insights into this parasitic race.

I'm delighted that the all too obvious "space alien" theory isn't the intended canon, for starters. Though he likes to leave it open to interpretation, Finnegan posits that this species may have evolved alongside us for eons, even drawing connections between their space-time distortions and Irish fairy folklore. A particularly juicy tidbit is his suggestion that the simulated housing communities grow like living fungus within what he calls "blister universes" on the Earth's surface. He also confirms that when Gemma passes through the layers of this pocket reality, she's indeed seeing the

current occupants of other houses, each "family unit" normally kept intangible and invisible to the rest.

And just as I suspected, the mortality rate of human caretakers is more an unfortunate side effect than by some insidious design; everything within a "blister" universe is artificial, from the food supplies to the illusion of sunlight, bereft of any consideration for human biochemistry at all, let alone proper nutrition. This scenario is painfully believable to anyone with any experience in animal or plant husbandry - just ask anyone who struggles to keep a saltwater aquarium in healthy balance, your average orchid hobbyist or

generations of bug nerds who have tried again and again to keep simple

pill millipedes happy and healthy for more than a few months, tops. Sometimes we truly have no idea why a given fish, insect or exotic succulent invariably shrivels up in an artificial environment, or we figure it out only after decades of trial and error.

Does this movie necessarily have an antagonist at all, and is it necessarily a non-human one? In another interview, Finnegan describes Martin as a manipulative entity, but notes that it's no moreso than our own children have evolved to do; he is following his species natural directives to survive, as simple as that. Conversely, what stands out a lot to me is that Gemma and Tom are never given any particular reason to doubt that they'll be freed at the end of the creature's rapid development and certainly no sign that they'll ever be harmed, but never overcome their revulsion for the

technically innocent being in their care. That revulsion is driven, for the majority of the narrative, by nothing more than the knowledge that Martin is a different species than themselves and the subtle ways in which he does not think or act as expected of a "real" human child, even when it's clear he

is, in his own way, enjoying his time with them.

As I touched on earlier and promised to expand upon, this scenario may be all too familiar to those who have grown up with a neurological disorder, perhaps even a physical disability or

any significant gulf in understanding between child and caretaker. Nobody asks to be different, and certainly no one ever wants to be a "problem" for anyone else by merely being born at all. I find that Finnegan's directing does well to frame Martin as just another sympathetic victim of circumstances beyond his control, and I'm left wondering if this is a cycle that could ever, in any way, be broken by a little more kindness. Could there, in fact, be any possibility of survival for loving enough caretakers? Could a genuine enough bond ever be formed that a "Martin" is driven to help its human parents escape containment, or at the very least, spearhead some effort to revise their methods and improve conditions for future hosts?

It's interesting to consider how this story could ever conceivably lead to a happy ending, but the odds are admittedly stacked heavily against it. It's entirely possible that these creatures

truly cannot feel concern or empathy for others, but it's still no reason to demonize them; their life cycle is every bit as impartial as their avian inspirations or any other known means of survival, and the greatest "monster" in Vivarium, arguably, may be the ruthless indifference of nature itself.

NAVIGATION: