For all their bizarre, sometimes grotesque adaptations, parasitic organisms are seldom

directly lethal to their hosts, having adapted to live in a careful balance with the animals they

depend on as food and shelter. Parasitoids, however, are a very different story. These are

defined as parasites which cannot complete their life cycle without the death of the host

organism, transitioning at some point from parasite, to predator. While many varied life forms

practice this sort of internal assassination, none are such devoted parasitoids as the insects

we call wasps.

directly lethal to their hosts, having adapted to live in a careful balance with the animals they

depend on as food and shelter. Parasitoids, however, are a very different story. These are

defined as parasites which cannot complete their life cycle without the death of the host

organism, transitioning at some point from parasite, to predator. While many varied life forms

practice this sort of internal assassination, none are such devoted parasitoids as the insects

we call wasps.

While there are many wasps devoted to attacking spiders, this particular species boasts an

exceptionally devious strategy. Targeting only the web-building spider Plesiometa argra, the

adult female lays a single egg on the host's abdomen. After up to two weeks of feeding on the

spider's blood, the larva administers a chemical to essentially reprogram the host's behavior.

It's normal for a spider to spin an entire new web on an almost nightly basis, but when our

parasitized spider begins its next construction project, something goes terribly, terribly awry; it

stops after the first few steps of the process and starts back at the beginning, repeating the

same actions until it has built only a tiny, dense, cocoon-like web. The spider traps itself within

this small prison, and waits motionlessly as the wasp consumes it and pupates within the

protective bag.

exceptionally devious strategy. Targeting only the web-building spider Plesiometa argra, the

adult female lays a single egg on the host's abdomen. After up to two weeks of feeding on the

spider's blood, the larva administers a chemical to essentially reprogram the host's behavior.

It's normal for a spider to spin an entire new web on an almost nightly basis, but when our

parasitized spider begins its next construction project, something goes terribly, terribly awry; it

stops after the first few steps of the process and starts back at the beginning, repeating the

same actions until it has built only a tiny, dense, cocoon-like web. The spider traps itself within

this small prison, and waits motionlessly as the wasp consumes it and pupates within the

protective bag.

Also known as the emerald cockroach wasp, this mere invertebrate was administering

delicate brain surgery before our kind even started to bang rocks together. With a single jab

of her stinger, the female penetrates a cockroach's brain and destroys precisely the right area

to disable its escape reflex. Next, she need only tug her victim's antenna like a dog leash,

guiding it dumbly into her burrow. There, she lays a single egg on the host's body and seals

the tunnel entrance behind her. Over the next two weeks, the larval wasp will slowly eat the

apathetic cockroach alive, prolonging its life through the process by saving its most vital

tissues for last.

delicate brain surgery before our kind even started to bang rocks together. With a single jab

of her stinger, the female penetrates a cockroach's brain and destroys precisely the right area

to disable its escape reflex. Next, she need only tug her victim's antenna like a dog leash,

guiding it dumbly into her burrow. There, she lays a single egg on the host's body and seals

the tunnel entrance behind her. Over the next two weeks, the larval wasp will slowly eat the

apathetic cockroach alive, prolonging its life through the process by saving its most vital

tissues for last.

The parasitoid lifestyle may seem a tad sadistic to us humans, but at least their hosts are

usually granted the merciful embrace of death once the wasplings are done consuming

their entrails. Usually.

usually granted the merciful embrace of death once the wasplings are done consuming

their entrails. Usually.

While most humans are familiar with wasps as angry, colonial, pepsi-diving summer pests,

the majority of species are tiny, barely noticeable parasites of other insects or arachnids,

integral in the population management of their fellow arthropoda. For nearly any insect you

can name, a specialized wasp exists to destroy it from within, including every insect we

humans recognize as a crop pest. As you can read more about in my first ever article for

cracked.com, many forms of plant life have even evolved chemical signals to communicate

with parasitoid wasps as a natural extermination service.

While these eerie and elegant creatures number in the tens of thousands, I've selected just a

handful of the most famous and unusual examples for a small peek into their beautifully chilling

lives.

the majority of species are tiny, barely noticeable parasites of other insects or arachnids,

integral in the population management of their fellow arthropoda. For nearly any insect you

can name, a specialized wasp exists to destroy it from within, including every insect we

humans recognize as a crop pest. As you can read more about in my first ever article for

cracked.com, many forms of plant life have even evolved chemical signals to communicate

with parasitoid wasps as a natural extermination service.

While these eerie and elegant creatures number in the tens of thousands, I've selected just a

handful of the most famous and unusual examples for a small peek into their beautifully chilling

lives.

| A tomato hornworm with wasp cocoons (source) |

When larval Glyptapanteles wasps tunnel back out of their caterpillar host, they still need to

cocoon themselves and undergo metamorphosis into adults, leaving them open to attack

from any number of predatory insects - even fellow parasitoids looking to exact some ironic

justice. To better survive in this vulnerable state, at least a single wasp larva will remain

behind in the caterpillar's body, keeping their half-eaten, barely living victim under control as a

sort of "zombie" bodyguard.

Over the following weeks, the caterpillar will devote the last of its energy to protecting the very

things that were previously drilling through its innards, perched over the cocoons like an

otherworldly mother bird, blanketing them with its own silk and flailing madly to repel other

insects. By the time the wasps emerge as adults, their undead servitor - and the siblings still

controlling it - will finally perish. We still aren't certain how the wasps choose which larvae

remain in the caterpillar, but I personally like to think that it may be determined from birth,

making certain larvae a sort of specialized, zombie-piloting caste.

cocoon themselves and undergo metamorphosis into adults, leaving them open to attack

from any number of predatory insects - even fellow parasitoids looking to exact some ironic

justice. To better survive in this vulnerable state, at least a single wasp larva will remain

behind in the caterpillar's body, keeping their half-eaten, barely living victim under control as a

sort of "zombie" bodyguard.

Over the following weeks, the caterpillar will devote the last of its energy to protecting the very

things that were previously drilling through its innards, perched over the cocoons like an

otherworldly mother bird, blanketing them with its own silk and flailing madly to repel other

insects. By the time the wasps emerge as adults, their undead servitor - and the siblings still

controlling it - will finally perish. We still aren't certain how the wasps choose which larvae

remain in the caterpillar, but I personally like to think that it may be determined from birth,

making certain larvae a sort of specialized, zombie-piloting caste.

Another wasp employing a "zombie guard," D. coccinellae targets female ladybird beetles or

"ladybugs," one of mankind's arbitrarily favored arthropods. A single larva will develop in the

host's abdomen, breaking out through the posterior (ouch) and spinning a cocoon at the

ladybird's feet. The beetle is left in a paralyzed state through the pupation process, tightly

clutching the cocoon and convulsing at irregular intervals, discouraging not only predatory

insects but larger vertebrates as well; a ladybird's famously endearing polka dots didn't

evolve to make it cute, but to warn other animals that its contents taste like burning vomit.

"ladybugs," one of mankind's arbitrarily favored arthropods. A single larva will develop in the

host's abdomen, breaking out through the posterior (ouch) and spinning a cocoon at the

ladybird's feet. The beetle is left in a paralyzed state through the pupation process, tightly

clutching the cocoon and convulsing at irregular intervals, discouraging not only predatory

insects but larger vertebrates as well; a ladybird's famously endearing polka dots didn't

evolve to make it cute, but to warn other animals that its contents taste like burning vomit.

D. coccinellae is a tad less beneficial to us humans than other parasitoids, as ladybird

beetles are themselves an important predator of crop-destroying aphids. Fortunately, almost

a quarter of parasitized ladies make a surprising recovery from being eaten alive and

enslaved.

beetles are themselves an important predator of crop-destroying aphids. Fortunately, almost

a quarter of parasitized ladies make a surprising recovery from being eaten alive and

enslaved.

In my list of the coolest and strangest caterpillars, I described how the young Alcon blue

butterfly (above) goes undercover in the nests of ants, deceiving them into feeding and

protecting it as they would their own queen. While these crafty creatures are guaranteed

protection from most of their predators, a certain wasp happens to be quite a bit sneakier.

butterfly (above) goes undercover in the nests of ants, deceiving them into feeding and

protecting it as they would their own queen. While these crafty creatures are guaranteed

protection from most of their predators, a certain wasp happens to be quite a bit sneakier.

The female Ichneumon eumerus can smell the presence of blue butterfly larvae from well

outside an ant colony, and once inside, releases a pheromone to confuse the ants into

attacking one another. Slipping through the ensuing chaos, the wasp implants a single egg

into each freeloading caterpillar, granting her own young the protection of an entire ant army;

a parasite hidden in a parasite hidden in plain view.

outside an ant colony, and once inside, releases a pheromone to confuse the ants into

attacking one another. Slipping through the ensuing chaos, the wasp implants a single egg

into each freeloading caterpillar, granting her own young the protection of an entire ant army;

a parasite hidden in a parasite hidden in plain view.

Common in dry, sandy climates, "velvet ants" are so named for the ant-like appearance and

dense fur of the larger, entirely wingless females, who pack a sting so painful they have also

been dubbed "cow killers" in parts of the United States. A lack of wings and an exceptionally

thick, rock-hard exoskeleton allows these brood parasitoids to withstand most attacks from

fellow bees and wasps, marching straight into their nests and laying their own eggs alongside

the host's. Velvet ant larvae will begin by feeding on host food provisions, moving on to

parasitize and ultimately consume the host larvae. Many of their victims are parasites

themselves, making some velvet ants hyperparasitic.

dense fur of the larger, entirely wingless females, who pack a sting so painful they have also

been dubbed "cow killers" in parts of the United States. A lack of wings and an exceptionally

thick, rock-hard exoskeleton allows these brood parasitoids to withstand most attacks from

fellow bees and wasps, marching straight into their nests and laying their own eggs alongside

the host's. Velvet ant larvae will begin by feeding on host food provisions, moving on to

parasitize and ultimately consume the host larvae. Many of their victims are parasites

themselves, making some velvet ants hyperparasitic.

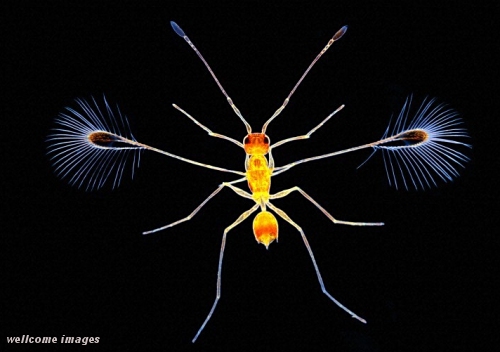

Also called fairy wasps or fairyflies, Mymaridae include the tiniest insects known to man, their

wings not so much sustaining their flight as simply steering them as they float through the air

like dust motes. Many species are even partially or fully aquatic, employing their wings as

swimming paddles. The small size of these "fairies" allows them to parasitize other insects

during the egg stage, laying several of their own within a single host egg. Young will mature

and even mate (with their own siblings) before breaking free of the host's egg shell, and target

such a diverse range of insects as beetles, grasshoppers, true bugs, flies and even lice.

wings not so much sustaining their flight as simply steering them as they float through the air

like dust motes. Many species are even partially or fully aquatic, employing their wings as

swimming paddles. The small size of these "fairies" allows them to parasitize other insects

during the egg stage, laying several of their own within a single host egg. Young will mature

and even mate (with their own siblings) before breaking free of the host's egg shell, and target

such a diverse range of insects as beetles, grasshoppers, true bugs, flies and even lice.

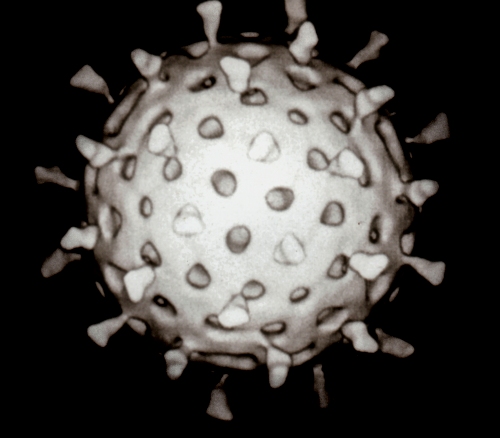

Polydnaviruses are found in a significant portion of braconid and ichneumon wasps,

themselves comprising the majority of parasitoid species. Far beyond your typical symbiosis,

the wasp's own DNA contains the complete genome of its respective polydnavirus,

information used by specialized cells in the wasp's reproductive system to assemble viral

bodies from scratch. These are injected into hosts alongside the insect's eggs, weakening

the victim's immune system and altering its metabolic processes in ways which benefit the

parasite.

Unlike independent viruses, polydnavirus particles lack the full genetic information necessary

to duplicate themselves, existing only when the time comes for the wasp's body to construct

them. The insect essentially retains exclusive rights to the complete viral "recipe," averting the

potential destruction of a precious host (or even its own larvae) were the virus to multiply on its

own.

Theories vary on how this relationship may have come about. It seems likely that an ancient

viral infection evolved a partnership with an early wasp host, while others have proposed that

wasp DNA evolved its own viral aspect, independently or from "borrowed" viral genes.

themselves comprising the majority of parasitoid species. Far beyond your typical symbiosis,

the wasp's own DNA contains the complete genome of its respective polydnavirus,

information used by specialized cells in the wasp's reproductive system to assemble viral

bodies from scratch. These are injected into hosts alongside the insect's eggs, weakening

the victim's immune system and altering its metabolic processes in ways which benefit the

parasite.

Unlike independent viruses, polydnavirus particles lack the full genetic information necessary

to duplicate themselves, existing only when the time comes for the wasp's body to construct

them. The insect essentially retains exclusive rights to the complete viral "recipe," averting the

potential destruction of a precious host (or even its own larvae) were the virus to multiply on its

own.

Theories vary on how this relationship may have come about. It seems likely that an ancient

viral infection evolved a partnership with an early wasp host, while others have proposed that

wasp DNA evolved its own viral aspect, independently or from "borrowed" viral genes.

Perhaps the most bizarre and startling characteristic of the parasitoid wasps isn't just their

gruesome method of childcare, their worldwide diversity, their symbiosis with plant life or

even the cerebral rewiring we've seen from several species, but their deeply, deeply intimate

relationship with another, far more ancient parasitic force.

gruesome method of childcare, their worldwide diversity, their symbiosis with plant life or

even the cerebral rewiring we've seen from several species, but their deeply, deeply intimate

relationship with another, far more ancient parasitic force.

| The Magical Lives of Parasitoid Wasps |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| The Secret Weapon |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| Ichneumon eumerus's inside inside job |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| Dinocampus coccinellae & the indentured ladybug |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| Glyptapanteles & the necropillar |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| Ampulex compressa & the cockroach lobotomy |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| Hymenoepimecis argyraphaga's spider straight jacket |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| Mymaridae: invisible fairies of death |

| ______________________________________________________________________________ |

| Mutillidae: the flightless cuckoos |