Written by Jonathan Wojcik

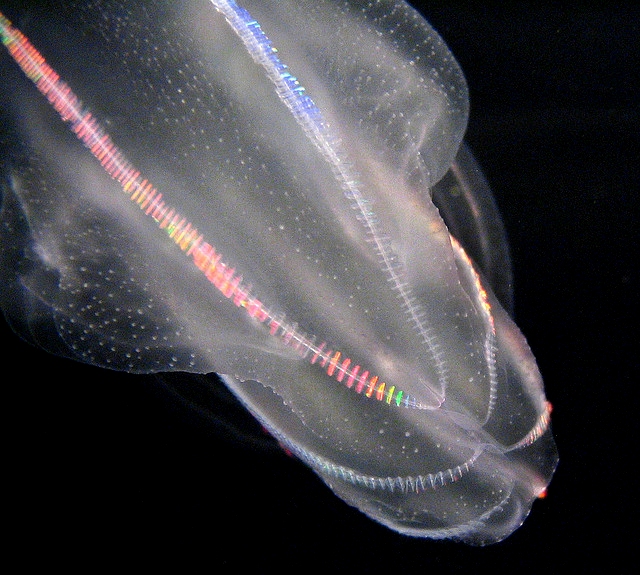

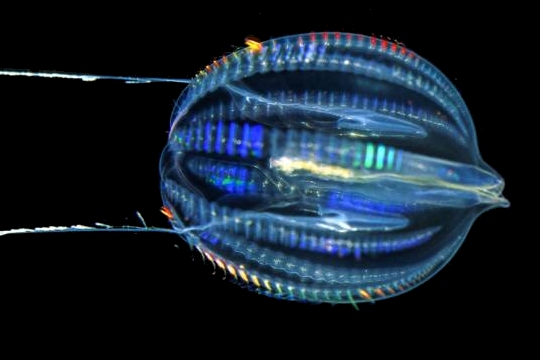

While commonly confused with the jellyfish and other Cnidaria, the comb jellies belong to their own distinct phylum, the Ctenophora, believed to be one of the planet's oldest and most basal forms of animal life. They are so named for their comb-like rows of beating cilia, which may appear brilliantly colored as they catch the light. This makes ctenophores the largest organisms to use cilia for swimming, like microscopic protozoa.

Like the jellyfish, ctenophores consist of little more than a gelatinous "pouch" lined inside and out with a thin layer of cells. Strictly carnivorous, they engulf microorganisms, other comb jellies or even small fish and crustaceans, rapidly liquefying prey with their digestive enzymes. Some comb jellies may eat several times their body weight in a day, and several species have become serious invasive pests.

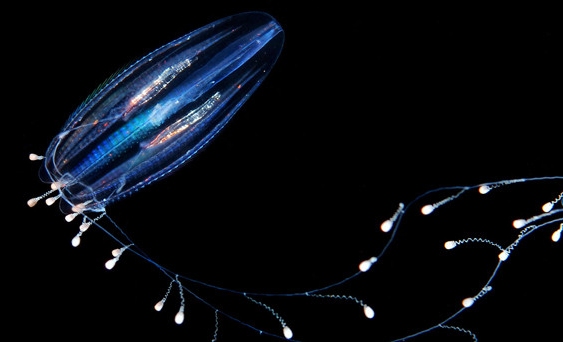

Different orders of comb jelly exhibit highly diverse body types; the Cydippida are the largest and most common order, with simple pod-shaped body and a pair of long, trailing tentacles lined with smaller tentacles or tentilla. Though they lack the stinging cells or cnidoblasts of jellyfish, ctenophores often line their tentacles with colloblasts, explosive cells filled with a glue-like fluid. Some Cydippids may also devour stinging jellies and incorporate the cnidoblasts into their own tentacles, much like certain nudibranchs.

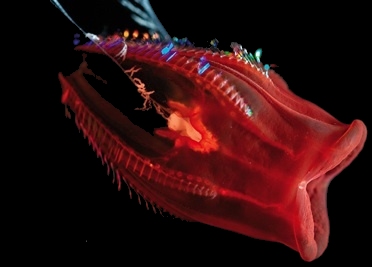

Cydippids of the family Lampeidae include the only known examples of parasitism in the ctenophores, their larvae latching onto the bodies of salps and slowly consuming their tissues. Salps continue to make up their entire diet as adults, but fully grown Lampea can devour them whole - even gobbling their way through entire connected salp chains or Blastozooids, as seen here.

Another unusual cydippid is Euplokamis dunlapae, whose bulbous, coiled tentilla have their own simple "muscles" and may be wriggled to attract small prey.

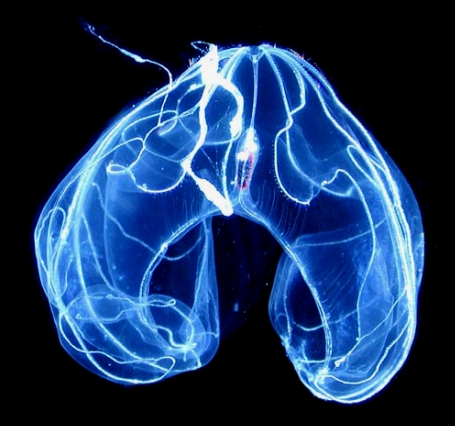

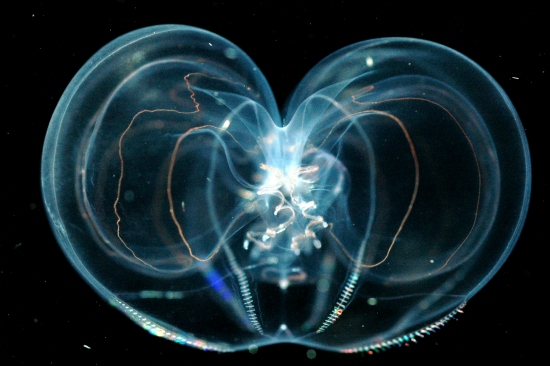

The Lobata are another large order, distinguished from the cydippids by two large lobes surrounding the mouth, which they can "clap" together when they need to swim quickly. Their tentacles are embedded in twisting grooves along their inner surface, trapping planktonic prey sucked inside by the cilia.

Thalassocalycida are often wider, rounder and more jellyfish-shaped than the other orders, lazily drifting in an open "bell" shape until they close shut around planktonic prey, as this one is demonstrating.

The two lone species of orderCestida may be the most beautiful and surreal of the ctenophores, often called "Venus' girdles" for their elongated, ribbon-like shape. With its mouth at the center, the rest of the girdle's serpentine form can be thought of as a pair of "arms" or "wings," which it can undulate rapidly to swim sideways in either direction.

Equally bizarre are the Platyctenida, combless comb jellies who live more like slugs or flatworms, creeping along what would normally be the interior lining and "mouth" of other ctenophores. Trailing their tentacles in the water to trap plankton, some species are domed and "horned" like these while many others are perfectly flat, often living harmlessly on the bodies of sea stars, cucumbers, corals or sponges where they look like little more than colorful patches of skin.

While by no means the weirdest or most elaborate, the Beroid comb jellies are my personal favorites, and I'm sure you can see why. Completely lacking tentacles or colloblasts, these swimming mouths prey exclusively on other comb jellies, swallowing them whole or taking bites out of of them with internal "teeth" formed from modified cilia. When not eating, they "zip shut" their mouths with adhesive cells and flatten out into a faster moving shape; sleek, ravenous sharks of the jelly world.

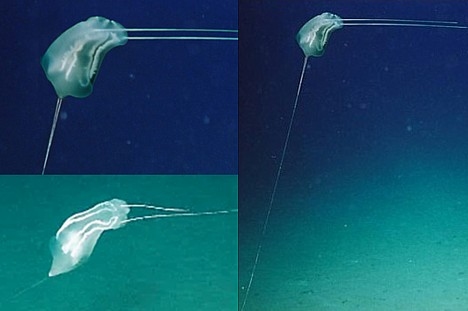

One of the most unusual ctenophores, and the last I'll be describing, is also one of the most recently discovered and still largely an enigma; it was captured on video in 2002, but its footage wasn't viewed until 2006, and no specimens have since been recovered. Still unnamed, we only know that this species seems to hold onto the seabed by a pair of long cables, drifting kite-like in the current with its feeding tentacles held out.