Written by Jonathan Wojcik

The Annelids are a group of animals most of you know best for the earthworms and leeches,

both belonging to the class Clitellata, but it is their sister class the Polychaeta which displays the

most extreme diversity, with over 10,000 known species found in brackish or salt-water environments around the globe. Unlike the

earthworms, Polychaetes can possess dozens of legs, claws, tentacles, antennae and complex mouthparts, an anatomy that has adapted to an insanely broad variety

of lifestyles. Some are beautiful, some are disturbing, many are both. We're going to count down my picks for some of the weirdest and wormiest, in no particular order or number, because on Bogleech, we appreciate far too many worms for a top ten.

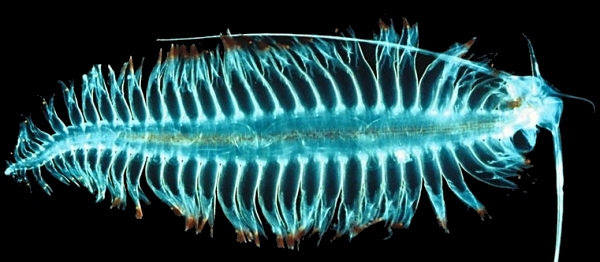

Tomopteris

An inhabitant of the deep sea abyss, Tomopteris may be one of the most beautiful of

all aquatic worms, its rippling transparent body as flat as a piece of paper, gliding through the water like a Chinese dragon kite. When attacked, it scatters thousands of luminous particles from its legs in an

attempt to confuse predators and cloak its escape. Its leg-like extensions or "parapodia" are also where its eggs develop, until they're shaken out into the water.

The Sea Mouse

Common in shallow, sandy waters, these cute little critters were given the family

name Aphroditidae after the Greek goddess of love, allegedly because they resemble a woman's pubic region. This is science, don't be a baby. Predators of other soft-bodied invertebrates, they creep about with their head plowing the sand, sniffing out their next meal.

To protect the rest of their bodies while they hunt, sea mice are

densely lined with sharp, crystalline bristles that filter sunlight into intense color

patterns, believed to function as a false toxicity warning. It's quite an elaborate bluff

on the worm's part; so elaborate, it could serve as a revolutionary model for fiber

optic technology. Each bristle is comprised of several million hexagonal cells or

"photonic crystals," the first such structures ever documented in the nature world and

more effective at manipulating light than any previous invention of man.

Pig Butts & Parchment Worms

Just a little less elegant than our previous worms, Chaetopterus pugaporcinus

literally translates to "worm like a pig's rear," with segments so flattened and inflated

that it loses any semblance to a worm-like shape. About the size of a grape, it drifts

in the deep sea abyss and dangles a net of sticky mucus believed trap planktonic

food. Lacking reproductive organs, the pig butts are believed to be larval, but their adult form has yet to be determined.

Other members of the order Chaetopterus mature into what are known as parchment worms, who hide their beautiful, delicate bodies in horseshoe-shaped burrows. The rippling of their many fins and paddles keeps water flowing through their tunnels, trapping bits of food in specialized filtration organs.

Syllid Sex-bombers

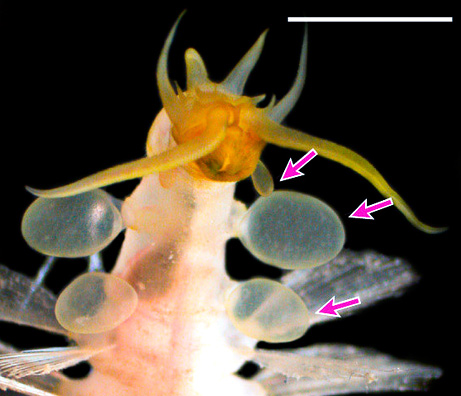

Several worms of the order Syllidae spend their entire adult life buried deep in the sand and mud of shallow seawater, feeding on tiny organisms well away from the prying eyes of predators. Unfortunately, they can't very easily propagate the species without leaving the safety of their burrow...or can they?

Though the mature worm is asexual, the posterior end of its body will divide into male or female sections with their own heads, eyes and swimming paddles. During the high tide, these portions break off, mingle with others of their own kind and explode in the water, releasing fertilized eggs. If they get eaten by a predator, the original worm can always just make more, mating remotely through its suicidal, cloned offspring.

Histriobdellidae

Among the tiniest of all Polychaeta, this peculiar group is so simplistic in form that it

was once considered its own separate phylum. Smaller than a pinhead, these worms both look and act remarkably like lice on the bodies of lobsters, crabs, isopods and other crustaceans. Sucker-tipped feet cling firmly to the surface of a host's smooth exoskeleton, and powerful drilling jaws penetrate the thick armor to feed on host fluids.

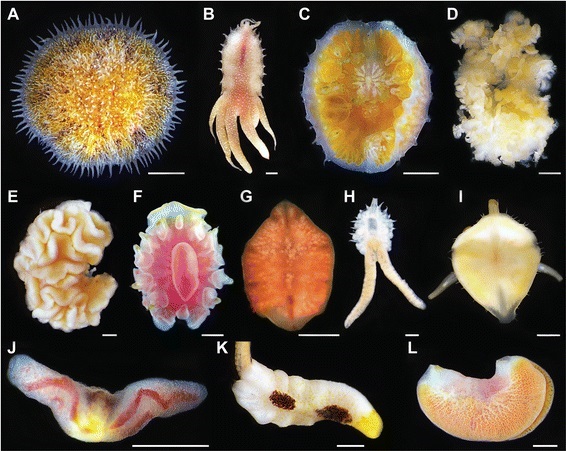

Myzostomes

Another group of ectoparasitic polychaetes are the Myzostomida, which come in a fantastic variety of beautiful and colorful shapes, many of them so shortened they resemble disks with a few pairs of fat, conical "legs" on their undersides. The resemblance to ticks or mites is more than aesthetic; living on the bodies of crinoids or "sea lilies," they insert their thin mouth parts to feed on host body fluids, and some may remain attached to the same feeding spot for the duration of their adult lives. There are some which insert their tube into the host's mouth, some which enter the digestive canal and even some that surround themselves in a cyst or gall formed from the crinoid's own tissues.

Vanadis worms

They might look a little ordinary at first glance, as far as polychaetes go, but Vanadis species boast several interesting features. For one, they're highly visual predators, with large, bulging and sophisticated eyeballs sometimes resembling a set of binoculars. Here's one with eyes like some bizarre owl, or possibly Wall-E, and it's showing off another neat adaptation of the group; lacking the sharp, tearing or crushing jaws of other polychaetes, the toothless pharynx of the Vanadis simply operates like a vacuum. Swimming in open water, they target small prey with those amazing eyes and launch their gelatinous food-sucker.

Symbiotic Scale Worm

Somewhere between a snail and a paperweight in agility, the keyhole limpet is easily

hunted down and preyed upon by one of the sea's most relentless killing machines, the

starfish. Easily, that is, if our limpet isn't packing heat; Certain tiny Polychaetes have taken to living almost their entire lives curled under the

rim of a keyhole limpet's shell, lying in ambush for their favorite snack - the soft,

gelatinous sucker-feet of sea stars. The worm gets food delivered right to its door, the

limpet lives to slither another day and the starfish has to explain to its starving wife and

kids that it went to pick up dinner and a worm chewed off its toes.

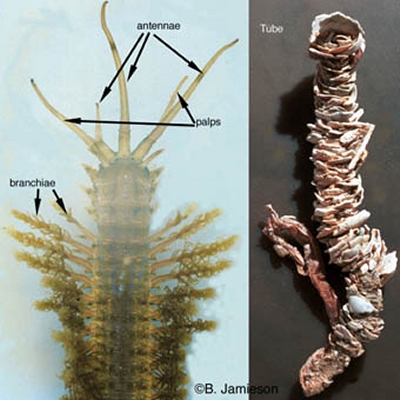

The "Bobbit" Worm

The Tyrannosaurus rex of worms, Eunice aphroditois is a colorful, burrowing

predator known to reach several feet in length, every inch lined in paralyzing venomous bristles. Burying itself up to the

antennae, it launches at passing prey with a set of huge, jagged mandibles, sometimes snipping fish clean in half!

The colloquial name "Bobbit worm" couldn't be more appropriate, derived from the infamous case of Loraine Bobbit, who caused a media frenzy in 1993 by slicing off her husband's penis with a pair of scissors. The worms themselves would make internet headlines in 2009 with the discovery

of "Barry," a four-foot specimen who nearly ruined an aquarium reef display as he

chewed his way through the live exhibit, ultimately earning a display of his own.

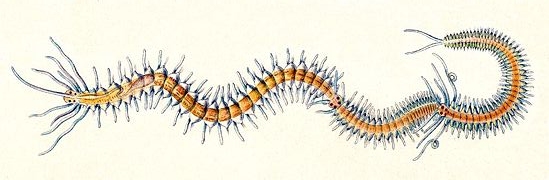

Diopatra

Lined with feathery parapodia, members of the genus Diopatra employ the same hunting technique as the bobbit worms, but aren't satisfied with a mere hole in the sand; these little decorators inhabit a tough parchment tube that may project several inches from the sea floor, camouflaged and fortified with small objects cemented to its surface by the worm's own mucus.

The Bomber Worms

A relatively recent discovery in the trenches of Monterey Bay, the genus swima share some similarities with the Tomopteris we met before, but have taken their defensive lightshow to a more advanced level:

Some of a Swima worm's gills are modified into nodules that produce a brilliant green light, even after the worm has broken them off and discarded them. A predator is much more likely to pursue these natural signal flares than the animal itself, earning these the nickname "bombardier" worms or "green bombers." Several different species have been identified, sharing some variation on the same biological fireworks.

The Methane Ice Worms

© Ian MacDonald, NOAA

Methane ice is a phenomenon once thought to occur only on other moons and planets in the far reaches of our solar system, until large deposits were discovered in the chilling depths of the sea, where the gas leaks from geological faults and crystallizes into a solid state. This frozen flatulation is unsurprisingly inhospitable to most macroscopic life, but the polychaete Hesiocaeca methanicola is an exception, feeding exclusively upon the bacteria which thrive in this unlikely environment. The adult worms can survive nearly a week without oxygen, and their eggs can drift for up to twenty days in the water's current, hatching only if they find another toxic tundra to call home.

The Sponge Hydra

Chris Glasby

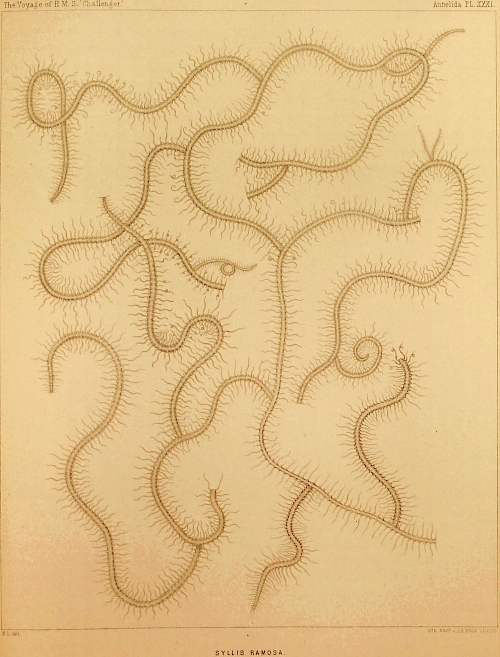

You're looking at just a small piece of one of the ocean's most anatomically outlandish freaks; a real creature which, in a reversal of the mythological hydra, grows an indefinite number of bodies branching from a single head. The head lies buried deep within the body of a sea sponge, the rest of its tree-like form winding through the cryptic labyrinth of the sponge's interior, hundreds or even thousands of posteriors poking out from the host's porous surface.

And why does it grow this way? we don't even know. It's not known what the animal actually feeds upon inside its sponge, or how it feeds at all, though at least two species exhibit this peculiar form, discovered more than a century apart; Syllis ramosa was identified by the Challenger crew in the laste 1800's, while Ramisyllis multicaudata was discovered by Christopher Glasby in 2006, off the coast of Australia. Genetic analysis shows only distant relation, implying an even greater world of branching sponge-worms yet to be discovered.

The Hydrothermal Tube Worms

When volcanic activity deep beneath the Earth's crust forces superheated water up through the sea floor, the result is a hydrothermal vent or "black smoker;" an underwater geyser of boiling hot minerals that would be instantly lethal to most of Earth's modern organisms. It's these very conditions, however, that likely supported the earliest traces of life on our planet, and now supports a denser concentration than any other environment in the sea.

Hydrothermal fauna includes a variety of polychaetes, but Riftia pachyptila, the giant tube worm, is by far the most famous - and rightfully so. While the tube worms of tropical reefs grow only inches in length, these blind sentinels may reach ten feet in height and grow more rapidly than any other marine invertebrate, flourishing in the noxious miasma of a smoker like some ghostly bamboo forest from the underworld.

Lacking a mouth or digestive system, these worms are sustained entirely by the organic waste of symbiotic bacteria, in turn thriving upon such raw materials as carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide, oxygen and methane.

The Bone-Eating Snot Flower

As the largest single concentration of meat in the animal kingdom, the death of a whale is

one of the deep sea's most celebrated events. The titanic carcass can take months or

even years to completely decompose, and becomes a veritable cornucopia of new life as

thousands of animals flock to the free buffet - some of which have evolved to feed on

absolutely nothing else.

Stripped of most flesh by squirming hordes of hagfish and ghostly white crustacea, a fallen leviathan's monolithic skeleton quickly comes alive with a tentacled bouqet of bizarre organisms known to some researchers as "zombie bone worms." Structured more like a plant than an animal, the female Osedax mucofloris - literally "bone-eating snot-flower" - lacks a mouth or stomach, relying on a network of "roots" to tap into its only food source; the fatty oils contained within whale bone. Like the thermal tube worms, it relies on unique symbiotic bacteria to process this nourishment.

When Osedax were first discovered as recently as 2002, biologists were perplexed by the

appearance of only female reproductive organs in every mature specimen, despite the

presence of male sperm and millions of fertile eggs. As it turned out, the "missing" male

worms were there all along, plentiful but microscopic, living inside the bodies of the

females. Continuously fertilized by her tiny inner harem, the lady snot-flower pumps

thousands of eggs into the surrounding water, to drift like dandelion seeds until another

colossal corpse appears on the sea floor.