Written by Jonathan Wojcik

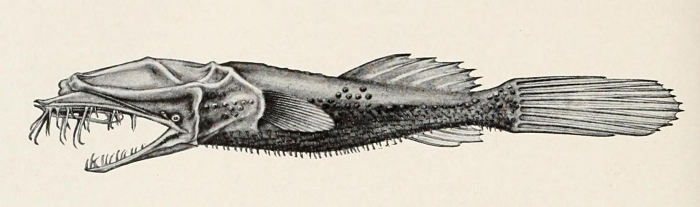

The quintessential vertebrates of the deep sea abyss are the Ceratioidei, also known as "deep sea anglerfish" or "sea

devils," most famous for the brightly glowing lures or esca on the end of a movable "fishing

pole" or illicium, modified from what would be the first bony ray of a dorsal fin. This

contraption is typically waved over the mouth, attracting other fish who mistake the

glowing tip for small prey. With over-sized jaws, hinged teeth and highly elastic stomachs,

the devils are prepared to blindly attack anything their bait might bring them, sometimes

swallowing prey several times their own size. Strange though these qualities may seem,

they are usually unique to the females of this group - while males are even stranger.

With sophisticated senses but an atrophied digestive system, a tiny male Ceratioid

cannot survive for long on his own, existing only to sniff out a female in the perpetual

darkness. On locating a mate, he digs his beak-like jaws into her flesh and remains there for the rest of his days. An enzyme melds together the skin of the two

lovebirds, their circulatory system becomes one and the male will lose virtually

everything not used in reproduction - including most or all of his head and brain.

Even among these weird animals is a great deal of more extreme variation. The "hairy"

anglers, family Caulophrynidae, have fins that extend into sensitive feelers for detecting

movement in the water.

Members of another family, the Gigantactinidae or "whipnose" anglers, have lures of

extraordinary length, with one six-inch species sporting a whip over six feet long.

Especially strange is that these fish typically swim upside down, with the whip dangling

towards the sea floor.

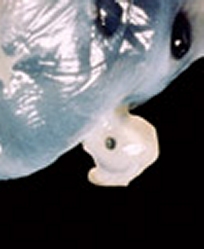

Perhaps the oddest anglers of all are the Thaumatichthyidae or "wolf trap" sea devils,

whose massive upper jaws fold in half lengthwise, like the leaves of a Venus fly trap, to

cage the prey before it is sucked into the throat. They are divided into genus Lasiognathus

and genus Thaumaticthys.

Lasiognathus species like these two bear the most

cartoonishly perfect "fishing rods" of any anglerfish, complete with bony hooks. Since

anglers don't normally allow prey to bite their precious lures, the purpose of the hooks is

unknown. They may simply make the lure look larger and more enticing, though it has been

postulated that they are used to grab the tentacles of squid or other soft-bodied prey.

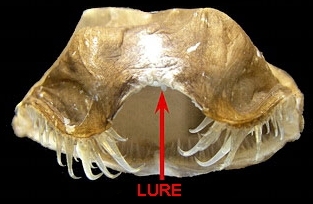

Genus Thaumatichthyis differs from Lasiognathus or any other angler with a lure that

reaches down through its upper jaw to dangle directly into its gaping mouth, with a small

"window" on the bulb itself that can adjust its brightness. They are much more benthic than

other Ceratioids, meaning they are most at home on or near the sea floor, and have oddly

enough been found with decayed plant matter and sea cucumbers in their stomachs,

implying omnivorous scavenging habits in addition to predation.

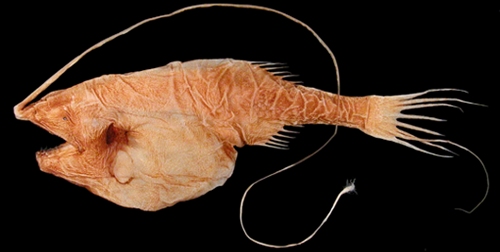

While there are certainly many more fascinating Ceratioids in the deep, the last one I'll be

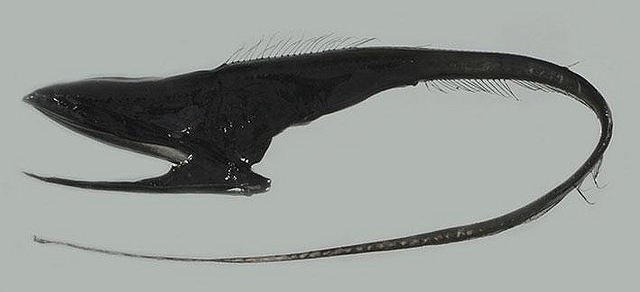

introducing you to is Neoceratias spinifer here, the only member of the Neoceratiidae. This

highly divergent angler has stopped angling altogether, lacking any trace of a lure or the

ability to produce light. Its sleek body as adapted towards more traditional, active hunting,

and its face full of hook-tipped, movable teeth makes a wicked trapping mechanism even

without a lure.

Barreleyes or "spookfish" comprise the family Opisthoproctidae, and boast some of the

strangest faces in the vertebrate world. Oval or cylindrical in shape, their binocular-like eyes are finely tuned to detect the silhouettes of prey even in pitch darkness, and in species like Opisthoproctus soleatus, shown here, the eyes may be permanently directed upwards. Their toothless mouths are adapted to suck in smaller prey, such as copepods or worms.

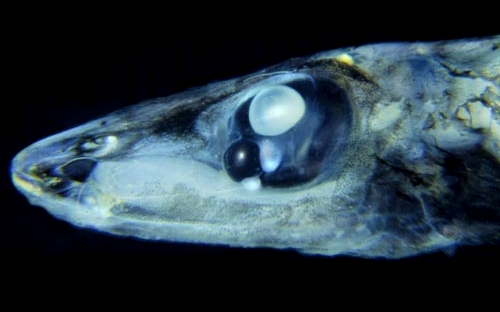

Winteria telescopa is a slightly different spookfish, with especially massive, egg-shaped eyes

directed forwards and a gelatinous, transparent head. Surrounding its snout are three red

specks of completely unknown function.

Photo by Hans-Joachim Wagner

Not to be outclassed by bigger eyes, Bathylychnops exilis goes for sheer quantity. A pair of bulges beneath its upturned eyes were once thought to be light producing organs, but were found to have functioning lenses and retinas of their own, making them "accessory" eyes. Later, it was discovered that the fish had yet a third set of eyes hidden behind the second. These tiny orbs lack retinae, but help to collect more light and direct it to the primary, uppermost eyes.

Perhaps the most bizarre of all is Macropinna microstoma, which possesses a transparent, cockpit-like dome over the eyes (the green orbs in this image) believed to protect them from the stingers of siphonophores, which they may steal food from. These eyes can move independently, like a chameleon. When it spies a siphonophore or jellyfish above, it aims its entire body vertically towards its potential meal.

Resembling a cross between a toad and a roast chicken, Ogcocephalus are a very different group of anglers than the luminous Ceratioids. Their upper backs often twist forward, overhanging their faces to form a large "snout," with the tiny illicium dangling in a nostril-like pit. These lures produce no light,

but secrete a chemical into the water that may lure prey by scent. Poor swimmers, Their fins are modified to walk along the sea floor. These creatures can actually be found even in shallower waters, where they often take on a more colorful appearance. When disturbed,

some species can inflate like a blowfish.

Anoplogastridae are often called ogrefish or fangtooths, well-deserved nicknames for these

snaggletoothed monsters. Though only six inches in length, they may be the fiercest little

scrappers in the deep, with the largest proportionate teeth of any known fish and resilient

enough bodies to have lived for months in captivity, far away from the pressurized conditions of the

abyss. The lower front teeth can grow so long that they must slide into special

sockets on either side of the brain for a fangtooth to close its mouth.

Tapetails, bignoses and whalefish are three creatures so unlike one another that they were once classified

as three completely different families, though only sexless, juvenile tapetails, male bignoses

and female whalefish had ever been observed. As it's not unusual to know a deep-sea

animal from only one sex or one life cycle stage, it took until 2009 for us to discover tapetails

in the process of becoming either bignoses or whalefish, turning three mysteries into one

answer. All three are now properly classified under the whalefish's original family name,

Cetomimidae.

Photo by Dave Johnson

As it matures into a bignose, once classified as Megalomycteridae, a male tapetail will lose

its stomach and esophagus while its mouth fuses shut. Devoting all of its energy to mating, it

will live off stored copepod remains for the rest of its short life, using its huge nasal cavities

to track down the scent of a female.

Photo by Kunio Amaoka

If our little tapetail was female, it matures into a whalefish, family Cetomimidae, which

appropriately enough engulfed the other two families once their nature was revealed.

Contrasting the males, these hungry beasties are mostly mouth and stomach, gobbling up

every other creature they can fit inside their elastic gullets. Some species even employ

their gills like additional mouth openings, slurping up small prey in three directions.

Considered top predators of the abyss, Stomiidae such as dragonfish and viperfish often

employ lures like those of the anglers, but are also built for fast and aggressive hunting.

Unlike any other group of fish, Stomiidae possess red-tinted lights just behind their eyes,

invisible to most other creatures. This allows these tiny sea serpents to illuminate their field

of vision without betraying their presence to most prey, and communicate to their own kind

without drawing unwanted attention. While not quite as dimorphic as the anglers, male dragons

are much smaller and relatively simpler than the females, without lures or even teeth. It is

believed that mature males do not feed, but live only to mate and die.

The larvae of some dragons may be the most unusual juveniles of any fish; thin, worm-like creatures

with eyeballs on long, flexible stalks. These stalks are slowly "reeled in" as the animal

matures, and can still be found permanently coiled inside the adult skull.

Photo by Edith Widder, Drawing by me

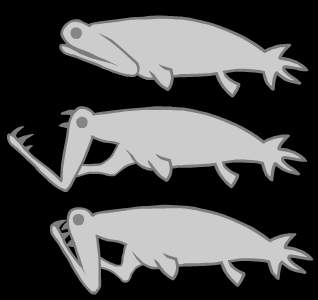

Some members of the Stomiidae are known as "loosejaws" or "rat trap fish" for their oddly

structured lower jaws, which reach out like the claws of a preying mantis. To reduce drag

and snap at prey in the blink of an eye, the jaws are disconnected from the open "floor" of

the mouth by a thin stalk, just like a man-made animal trap.

By Richard Ellis for his wonderful book, Deep Atlantic.

The peculiar "tube eye" or "threadtail," Stylephorus chordatus, is the only known member of the Stylephorus genus, and one of my personal favorite fish. Its jaws are enclosed in a membrane with only a tiny opening, creating a powerful suction when the jaws are expanded. The whole structure is remarkably similar to a bellows, and can expand an incredible 38 times its original volume. I have to wonder who thought it should be named just for its eyes or tail. I nominate hooverface for a new common name.

The body of HOOVERFACE is less than a foot long, but the whiplike extension on its tail fin

more than triples its overall length.

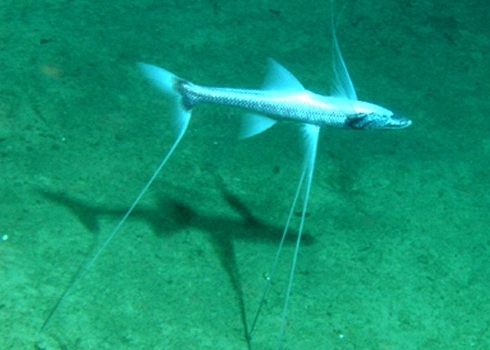

Though its body is little over a foot in length, The eyeless "tripod fish" Bathypterois grallator stands

up to a meter off the sea floor on three fins with incredibly elongated tips. Swimming only

when necessary, it spends most of its time standing in a single spot, eating whatever tiny

creatures may bump into its outstretched front fins - a feeding tactic more commonly seen in

sessile invertebrates, such as anemones, crinoids or barnacles. When a tripod fish does

decide to swim, its "legs" lose their rigidity and trail behind it like soft tails. How the

appendages go from flaccid to stiff is unknown, but perhaps they're pumped with fluid when

the fish wants to rest, not unlike certain other things in nature that can stiffen. Unusually for a vertebrate, tripods are hermaphrodites and capable of self fertilization.

A close relative of the tripod fish lacks its unusual feeding method, but compensates with an

oddity all its own; grideyes have never been observed alive and their habits are largely

unknown, as is the purpose of their incredibly strange sight organs. These flat, grid-like structures

call to mind the eyes of an insect, and emit a vivid glow of unknown function.

The first true eels on our abyssal tour, Nemichthyidae have thin, tweezer-like jaws that bend

outwards from each other, an arrangement that at first appears almost useless. It was long debated

how these fishes actually ate, but we now know that their tiny, backwards-facing teeth allow

them to "ratchet" small crustaceans into their mouths with a series of rapid chomps.

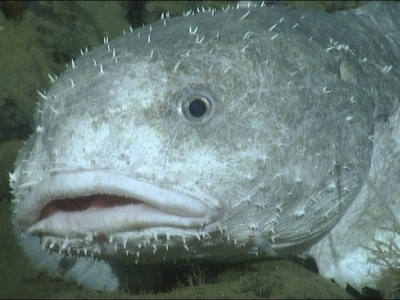

Featured on countless "freaky animal" blog posts, this comical puddle of flesh has become one of the most popular photographs of any

deep-sea animal on the internet. It's only on land that this heavily damaged specimen looks so peculiar, however; like a jellyfish, the density of its body is less than that of water, holding a much more

consistent shape in its natural environment:

Disappointing though it may be, the Psychrolutidae or "fatheads" look a lot less outlandish

underwater, though certainly unusual for Scorpaeniformes, which also include the stonefish and the beautiful lionfish of brighter waters. Adapted to expend as little energy as possible, these blubbery bags drift

lazily in place for hours, swallowing whatever food just happens to drift close enough.

Unusually for abyss-dwellers, they have been observed carefully protecting their eggs and

young in community nesting sites.

For a much weirder Scorpaeniform, look no

further than the abyssal snailfish. Snailfish throughout the sea exhibit strange and seemingly

degenerate behavior, even living in the bodies of scallops or other invertebrates, while

in the deep ocean, certain species routinely lay their eggs in the gill chambers of giant spider

crabs. As they cause no direct harm to the crustaceans, this relationship is not parasitic,

and may even be mutualistic when the fish eat bits of refuse and parasites off the crab's

body.

Unknown specimen - a larva?

The Saccopharyngiformes (literally "sack throats") are sometimes known as "pelican eels," "umbrellamouth gulpers" or more commonly "gulper eels," though not technically true eels at all. Their thin, flexible jaws can flare open just like an umbrella to engulf even relatively massive prey, and like the anglers, their stomachs can stretch several times their original size. It's an excellent survival strategy: a low body mass requires less nourishment, and an expandable one can store larger amounts for longer periods of digestion. Gulpers are predators making the most out of a minimum.

In some species, the tip of the tail actually ends in a tiny light theorized to serve as a lure.

These gulpers have been observed floating in place, dangling their tail-lights just inside their gaping

maws.

Image: W. Leo Smith

Image: W. Leo Smith

An unusual cousin of the gulpers, the tiny Monognathidae or "one jawed" eels, have lost the bony structure of their upper jaws entirely, possessing only a hooklike lower jaw and a venomous fang in the roof of the mouth.

Another glutton of the gloom is the unrelated Black Swallower of the genus Chiasmodon, known

to engulf fish more than four times its length. In some cases, the swallower is unable to digest prey

before it begins to decompose, and the resulting gases send the tiny terror floating fatally

to the sea's surface. It is thought that a swallower first bites prey on the tail, then chomps its

way up the victim's body with its ratchet-like teeth, swallowing it inch by inch.