Written by Jonathan Wojcik

Jellyfish, corals and anemones are already pretty damn weird, so what happens when mother nature goes

off the deep end and decides they still aren't weird enough? As brainless, tentacled blobs of slime go, these

guys are the most extreme, unusual and just plain fascianting; the brainlessest, tentacledest, blobbiest blobs in the sea!

The Fly Trap Anemone

Meals can be few and far between in the deep sea abyss, and Actinoscyphia doesn't take any

chances. Its sticky, stinging tentacles line a folded maw like the leaves of its namesake, snapping shut over

victims who could have struggled free from a more conventional anemone. If this sounds familiar, you may

have previously read about the deep ocean's carnivorous tunicates. If attacked, the fly-trap anemone

releases a bioluminescent slime into the water, which may serve to attract the attention of even bigger

predators - the anemone's enemy's enemies.

The Stalked Jellies

Tiny jellyfish that abandoned swimming, the Stauromedusae have an adhesive stalk growing from the center

of their bell, which they use to attach "head"-first to solid surfaces and act more like their anemone cousins, trapping

whatever drifts by. If they need to move, they may roll or "somersault" in a darling inchworm-like manner or

release their stalk and ride the current. Many species prefer to attach themselves to particular seaweeds,

colored to blend in with marine foliage.

The Parasitic Anemone

One of the few parasitic Cnidaria outside the myxozoa, Edwardsiella lineata spend their larval stage buried in the body of a Ctenophore or "comb jelly", stealing food straight from the host's gut. After

leaving their host, they may seek out another or mature into more typical, fully carnivorous anemones.

The Upside-down Jellies

Many species of jellyfish cultivate photosynthetic algae in their own

tissues, sustaining themselves off no more than sunlight. Of all these solar-powered jellies, the Cassiopeia

seem to take it the farthest, spending most of their lives lying upside-down on the sea bed, still constantly

pumping their bell to avoid floating away. Imagine a wind-up toy that keeps pushing itself against the same wall, and you've got an idea of how these jellies stay in place. This ridiculous behavior not only gives the jelly's algae garden maximum sun

exposure, but makes it more difficult for predators to sneak around the stinging tentacles and attack the body. Upside-down jellies often congregate in large numbers, forming group "gardens" to protect one

another.

Literally this.

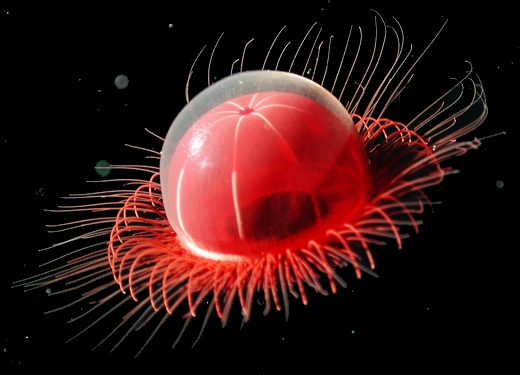

Big Black and Big Red

Rarely seen by man, very little is known about the deep-sea titan Stygiomedusa gigantea. Lacking the fringe tentacles of normal

jellyfish, it instead trails abnormally large, sheet-like oral arms over twenty feet in length, billowing from a bell

more then a meter across and grey-black from top to bottom. Though harmless to us, there's something even I find unnerving about this dark, faceless cloak drifting through the lightless deep.

Slightly less imposing is Tiburonia Granrojo or "big red," long mistaken for a juvenile gigantea until its

recognition as a distinct species in the 2000's. It, too, has only oral arms, without stinging tentacles, but grows only three feet across. Not as nightmare-inducing as its darker cousin, but still large enough to swallow your head.

Deepstaria

Related to our black and red giants, the two known species of Deepstaria lack tentacles or even prominent arms, engulfing prey whole into their huge, broad bells like living, swimming stomachs, lined with a webbing of vein-like channels to evenly distribute digested nutrients. Deepstaria reticulum is the smaller, redder and baggier of the two, seen here with its bell closed tight.

Deepstaria enigmatica is larger and clearer, holding itself open in this shot. Interestingly, every specimen ever observed has been inhabited by a single isopod crustacean, presumably a parasite.

You can see Stygiomedusa, Tiburonia and both Deepstaria species in action in this gorgeous footage from MBARI!

The Highlander of Jellyfish

Less than half an inch in length with a fairly conventional anatomy, Turritopsis nutricula is a tiny Hydroid (not truly a "jellyfish" as

most sources call it) with a coveted gift unheard of in most of the animal kingdom: biological immortality.

While it can certainly be killed like any ordinary creature, it does not naturally age and die like one, instead reverting back into its immature polyp stage to begin life anew. This commonly used photo

actually portrays a different, but roughly identical-looking species in the same family. It is not currently known if this

species - or any other species - share nutricula's special trick.

The Aggro-nemones

This "aggregating" anemone may look normal on the outside, but engages in some of the most

complex and violent behavior of all anemonekind. Constantly cloning itself, it builds a massive colony of

genetically identical anemones who show extreme hostility towards any genetically dissimilar anemone,

resulting in brutal turf wars between rival clone-armies. Clone wars, if you wall.

As the tide rises, the colony sends small "scouts" to expand its borders, protected by larger "warrior" anemones who stretch out their bodies and inflate their stinging tentacles. Special tentacles called "acrorhagi" are used exclusively to attack other anemones, and leave behind stinging "peels" which necrotize anemone tissue. As the colony spreads out, their numbers are filled back in by specialized reproducers, who stay put and replicate while the warriors are keeping them safe.

Despite their aggressive ways, these anemonazis are another Cnidarian fed by little more than symbiotic

algae, using their stingers primarily for their epic territorial disputes.

The Hermit-crab Polyps

Faced with the problem of where to actually grow in the sludge of the deep-sea floor, the Zoanthid (neither anemone nor coral) Epizoanthus paguricola devotes its swimming larval stage to tracking

down an empty snail shell and rapidly overtaking it. Its goal is to eventually be

carried by a hermit crab, which gains even better protection from the stinging tentacles than it ever would

from an ordinary snail shell - also rarely found in the deep.

The Fishing Jelly

Many creatures of the sea - especially the dark abyss - employ

"aggressive mimicry," meaning that parts of their bodies function as

tasty-looking lures to attract prey. Viperfish, gulper eels, cephalopods

and the famous anglerfish are all examples of aggressive mimics, but no

cnidarian had ever been observed "fishing" in this manner until the

discovery of Erenna in 2003.

This worm-shaped siphonophore is guided by a chain of swimming

polyps (left in the first photo) with rows of feeding, reproductive and

stinging polyps trailing behind. Its stinging appendages end in luminous

red organs which closely resemble tiny copepod crustaceans, even

twitching in the water as though "swimming." After Erenna's discovery, it

became apparent that many other deep-sea siphonophores may also

employ lures to attract hungry fish - tactics we never expected from these

brainless invertebrates.

The Cuckoo Jelly

Another non-Myxozoan parasite, Polypodium hydriforme is so unusual that it constitutes the only species in its own unique class of Cnidaria, the Polypodiozoa. This would be like having only one species of coral in the entire world, no anemones, no other Anthozoa of any sort. As tiny larvae, Polypodium lives within the egg cells of female sturgeons, paddlefish and related species, its body essentially "inside out" to digest the surrounding cell. When the host is about to spawn, the parasite flips right-side out, engulfing the remaining egg yolk and revealing its long, thick tentacles.

Sustained only by the nutrients of the stolen yolk, the free-living stage exists only to reproduce, multiplying rapidly by fission before developing proper sex organs and infecting new fish with thousands of larvae.

The Jelly Worm

If you've read my overview of Cnidaria, I'm sure you expected a Myxozoan to make this list, and as physiologically deviant as the jelly-germs already are, Buddenbrockia plumatellae is a deviant among deviants. While other myxozoans manifest as an infectious layer of slime, these horrors emerge from their spores as solid, highly mobile worms, completely unrelated to any other worm-like organisms on our planet and structurally unlike any other Cnidarian. While every other jelly consists of just two layers, Buddenbrockia possesses a third, housing tiny strands of muscle. While every other jelly displays radial, wheel-like symmetry, Buddenbrockia has streamlined into a closed tube with no designated front, back, top or bottom. Only one thing remains as an obvious indicator of its ancestry: the many cnidoblasts lining its body, used to harpoon the tissues of its Bryozoan hosts.