Written by Jonathan Wojcik

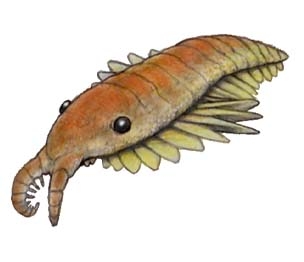

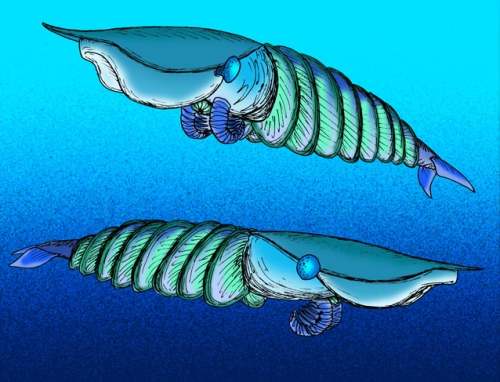

Over 500 million years ago, Earth's young fauna were terrorized by a beast with a circular, toothy mouth, a pair of spiny arms on its face and a torpedo-like body lined with rippling fins. Reaching up to three feet from head to tail, it was at the time the largest predatory animal known to inhabit our world, an invertebrate tyrannosaur reigning supreme before the evolution of vertebrates or the invasion of animal life on land.

Despite its impressive size, Anomalocaris was first discovered in seemingly unrelated, cryptic fragments that would take nearly a century to join one another. The name "Anomalocaris" or "strange shrimp" was first given to fossilized remains of the segmented facial limbs, interpreted in 1892 as the tails of shrimp-like animals whose heads, for whatever reason, had never fossilized. Separate fossils of the iris-like mouth were believed to be jellyfish given the name Peytoia, and imprints of the leaf shaped body were taken for

some form of sponge, coral or echinoderm dubbed Laggania.

It wasn't until 1979 that paleontologist Derek Briggs theorized Anomalocaris was in fact the appendage of a much larger animal, a theory he would prove in 1981 with the help of Harry Whittington. Re-examining a fossil of Laggania with a Peytoia curiously "lying" across its base, they uncovered a pair of Anomalocaris hidden deeper in the ancient rock, and thus three imaginary animals Voltroned together into one very real and magnificent monster.

Lacking apparent legs, Anomalocaris is thought to have rippled its flattened paddles like a cuttlefish, hovering in the water column and snatching up prey in the spiny arms. Much of its diet was believed to

have been trilobites, fossils of which are often found with mysterious half-circle bite marks that may have been made by Anny's circular maw. Some have gone so far as to postulate that Anomalocaris and its kin

were the only reason so many trilobites possessed complex eyes on the tops of their heads, and even the reason they evolved to roll up into balls. Others have contested the creature's trilobite diet, alleging that Anomalocaris was better suited to soft bodied prey, though it may very well have cracked trilobite shells with its arms before sucking out the innards.

In honor of its misunderstood history, the name Laggania was eventually given to another species of Anomalocarid, a more bullet-shaped creature adapted for a slightly less aggressive lifestyle. Only half as long as its sister and lacking the fan shaped tail, the "new" Laggania was probably a slower moving animal and its soft, gaping mouth better suited to swallowing smaller food particles whole. Its claws bore stubby spines near their tips, but flattened paddles closer to the base, probably for sweeping plankton or sediment into the mouth.

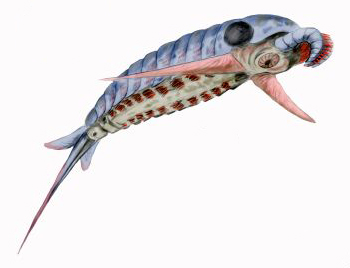

The "jellyfish" Peytoia, on the other hand, was eventually reincarnated as Parapeytoia, an Anomalocarid genus possessing twin rows of actual legs in addition to its flattened paddles. Obviously spending more time on the sea floor than its swimming sisters, its arms stuck straight out like the claws of a scorpion, with

large spines that could have easily grasped fellow bottom dwellers. Smaller than either Anomalocaris or Laggania, it may have been preyed upon by some of its own immediate family.

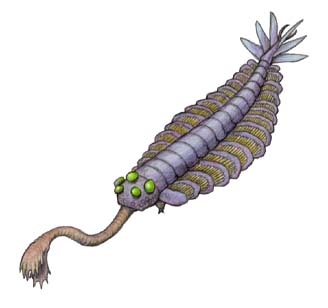

The discovery of Anomalocaris would add a little context to an even older, weirder fossil, Opabinia, discovered in the early 1970's. Almost surely related, Opabinia boasted a very similar body plan to the strange shrimp, albeit with five bulging eyes and a single, flexible "trunk" ending in a spiny clasper, possibly a fusion of the "arms" in Anomalocarids and perhaps used to fish out burrowing prey. For reasons unknown, the small mouth appeared to point backwards, towards its tail. Paleobiologists still puzzle over just how to classify this weirdo, currently placing it in its own unique sister group to the Anomalocarididae, the Opabiniidae.

Delicate and spindly, with a tiny mouth and complete lack of eyes, Kerygmachela seemed like a highly

specialized Anomalocarid...but for what? Its paddles suggest a swimmer, but without sight it may have lived in

dark, enclosed environments or remained close to rocky surfaces, navigating by touch.

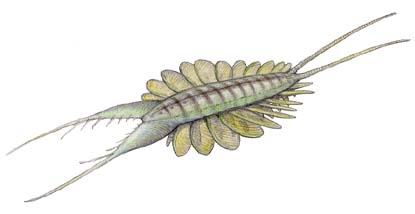

Pambdelurion was even more divergent, an eyeless bottom crawler whose broad, fuzzy arms probably

swept plankton into its toothless mouth or filtered soft sediment like a modern sea cucumber. In this

illustration you can really see the family resemblance to velvet worms.

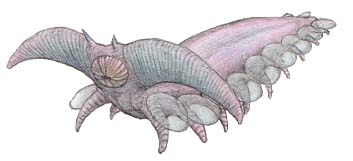

Most anomalous of all was perhaps Hurdia, which had neither legs nor paddles but did possess a strong

swimming tail and a massive, hollow "shield" of unknown function. Shaped like an overturned boat, the

headgear could have been filled with a buoyant gas like the shell of a nautilus, keeping the animal afloat

with only its tail needed for propulsion. Its relatively weaker claws may have restricted it to smaller, softer

prey than Anomalocaris or even the life of a scavenger. My own hypothesis? If it really was adapted to

travel with minimal effort, it may have preyed mainly upon jellies and drifting hydrozoa in ocean currents.

While there are still other Anomalocarididae, Schinderhannes bartelsi may be the most surprising

discovery since the original; both a more recent find and a more recent extinction, recovered in 2009 from

lower Devonian slate. This fossil proves that Anomalocarids survived for at least 100 million years longer

than previously believed, long enough to share our globe with some of the first four-legged land animals.

Even more impressively, S. bartelsi's anatomy raises at least the possibility that animals like these weren't merely close cousins to arthropods such as insects, arachnids and crustaceans, but could have been their true precursors. This would place the entire arthropod phylum as a group within the Anomalocarididae, meaning that these ancient aliens, at one time the planet's most gargantuan killers, are still with us today...they've simply taken on forms with such varied names as spiders, ants, barnacles, butterflies, beetles, botflies, stomatopods, centipedes, fireflies, body lice, dust mites, bumblebees, mosquitoes, mantids, sowbugs and tens of thousands of other creatures comprising the majority of all life on Earth. Creatures our entire ecosystem now depends upon, but would easily continue to adapt and thrive without us.

Well played, strange shrimp.