A fun-filled summary of Parasitic Crustaceans by Jonathan Wojcik

AAAAAHHHHHHHHHHH.

Virtually every animal group has its examples of parasitism, and the Crustaceans - best known as the crabs, lobsters and shrimp - are no exception. Primarily found in the ocean, Crustaceans include some of the world's strangest and even most disturbing parasitic arthropoda. Some wallow like tapeworms in the host's innards, some burrow deep into flesh and some practice forms of "mind control." Some, like the above "anchor worms," have even lost all semblance of arthropod anatomy, taking on forms more like otherworldly fungi than animal life.

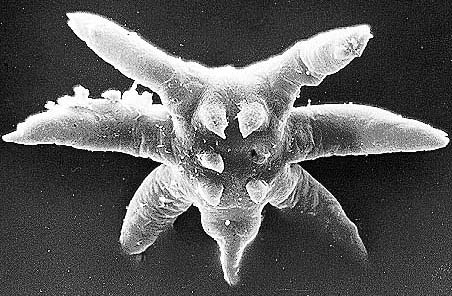

One of the simplest and most common examples parasitism among Crustacea is the Argulus, a form of copepod. Often called "fish lice," these dome-shelled, beady-eyed vampires cling tightly to scales with a set of antennae modified into huge, barbed suckers.

You think you've had "crabs?"

Some Argulus feed on the host's mucus coating, leaving the underlying scales vulnerable to bacterial or fungal infections. Others use a set of scraping mouthparts to dig through the flesh of the host and inject a digestive enzyme, breaking down tissues into drinkable sludge.

Remarkably similar in behavior to ticks, Gnathiidae are isopods, like woodlice and pillbugs, but lie in wait until a fish swims close enough to latch onto. After gorging on blood for several days, the fish-chigger molts into a non-parasitic stage until ready to feed again, alternating in this manner several times in its life.

Most female Gnathiids are difficult to tell apart at reproductive maturity, but males vary enough to identify more easily. It's amazing how much this one looks exactly like an unrelated, terrestrial stag beetle...with a few more limbs, of course. The massive "horns" are probably used to grasp females during copulation.

The most conventional looking and possibly the cutest Crustacean you're going to see here, the Pinnotheridae or "pea crabs" are soft, tiny little globular crabs who enter their hosts as larvae and remain there as they feed and grow. Hosts are most commonly mussels such as oysters, but other species may make their homes in the body cavities of echinoderms (such as urchins or sea cucumbers), the shells of snails, the tubes of certain worms or even the gills of sea squirts. Within these filter-feeding animals, the crabs have easy access to all the plankton they can eat, not unlike a tapeworm in the gastric system of a vertebrate.

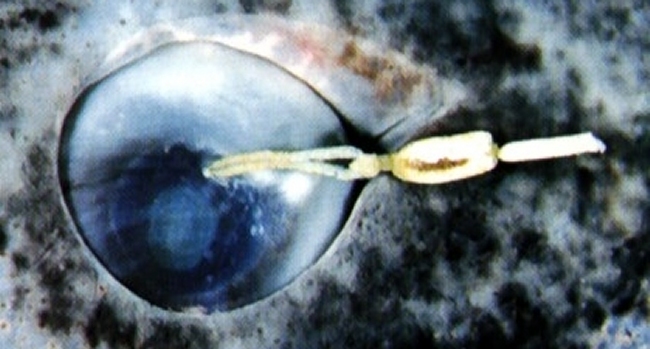

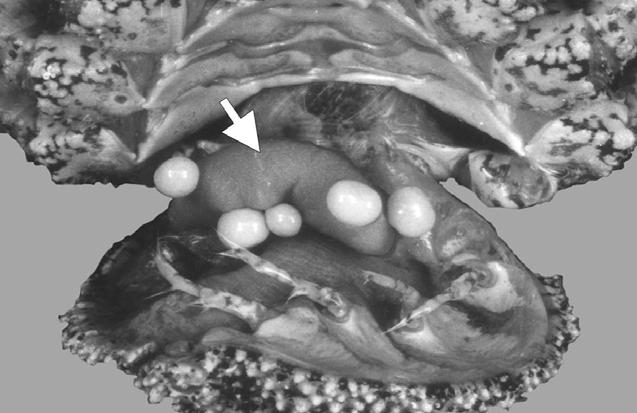

The arrow here is pointing to the copepodChoniomyzon inflatus, and it's the only one visible in this photo. The other orange globes are the eggs of a smooth fan lobster, Ibacus novemdentatus, carried under the tail of their mother. The mama lobster will often groom her egg mass and carefully pick out anything that doesn't belong, so this egg-eating louse almost perfectly mimics the shape and size of the real thing. A circular sucker allows it to grip tight to the host's eggs, and its puncturing mouthparts allow it to feed on their contents. Two other, similar species attack the eggs of a particular spiny lobster and a spider crab, though many more likely exist!

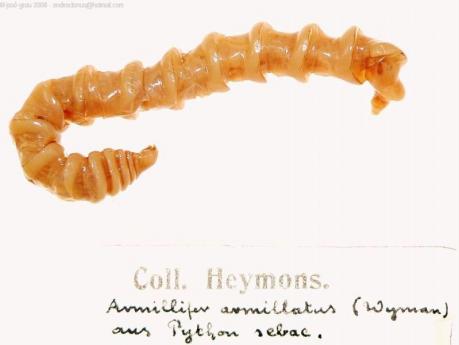

Often called "tongue worms" for the tongue-like shape of certain species, the peculiar "Pentastomida" were never considered crustaceans until the 1970's, a classification that remained uncertain until advanced molecular analysis. The confusion wasn't helped by their choice in hosts, primarily land animals including mammals, birds, amphibians and especially reptiles. Crocodilians, lizards, turtles and snakes all play host to their own unique Pentastomids, typically feeding on blood from the lungs and sinuses. The latin name translates to "five openings," as many species have a mouth surrounded by four sucker-tipped arms once mistaken for additional mouth openings.

Pentastomids perpetuate in a similar fashion to the unrelated tapeworms; eggs passed from a host body (by defecation or coughing) must be ingested by an intermediate host, usually a fish or small mammal, where the stubby larvae (like this fossilized specimen) hatch and encyst themselves. When ingested in turn by a predator, the baby tongue worms break out of their new host's esophagus and head for the respiratory tract.

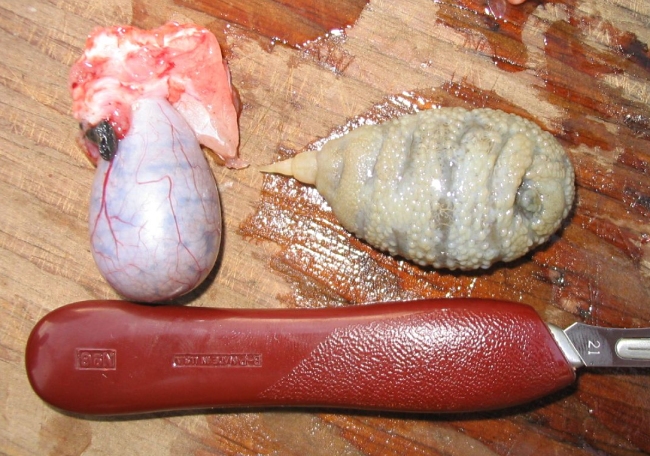

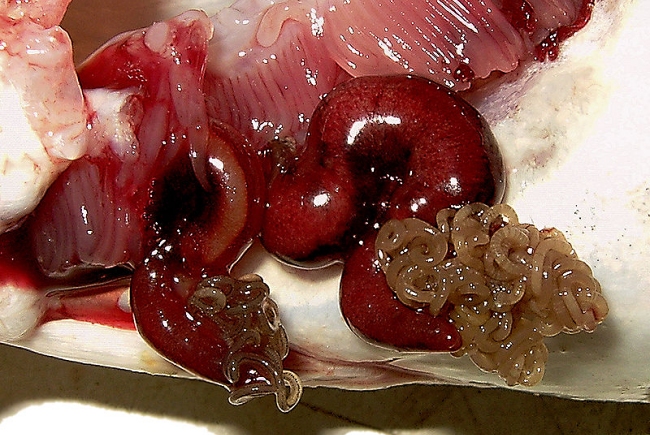

What you're seeing here was excavated by Dryodora from the anus of a hapless rockfish. The rectum is a preferred attachment point for many species of Sarcotacid, another group of copepods whose females develop into the huge, warty pustules you see here. Somehow, the lovely lady causes the tissues of her host to grow a protective bag or gall around her body, lined with veins from which she somehow obtains blood. Yes, "somehow" - the actual feeding mechanism isn't fully understood.

Photo by Professor R. Lester, posted by Scrubmuncher

Joining the female in her anal skin-bag can be anywhere from one to several dozen tiny, arrow shaped males (top) who spend their lives squished between the gall wall and their bloated, gargantuan mate, competing with each other to fertilize her eggs. Like their eating habits, little else is known about their life cycle.

Another group closely related to the barnacles, the reproductive habits of these little weirdos are poorly understood, but they can be found growing in or on the bodies of echinoderms and jellies, their bodies reduced to almost clam-like limbless blobs.

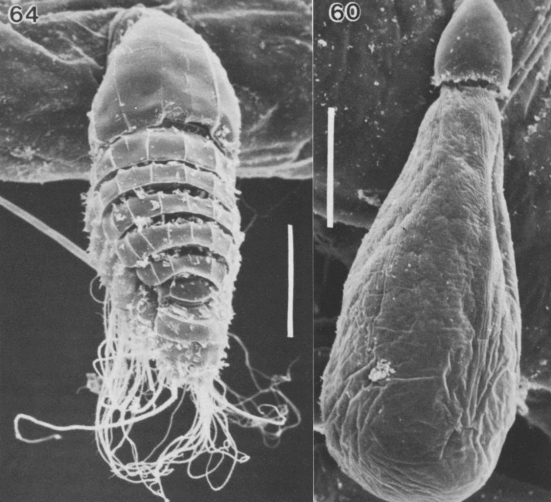

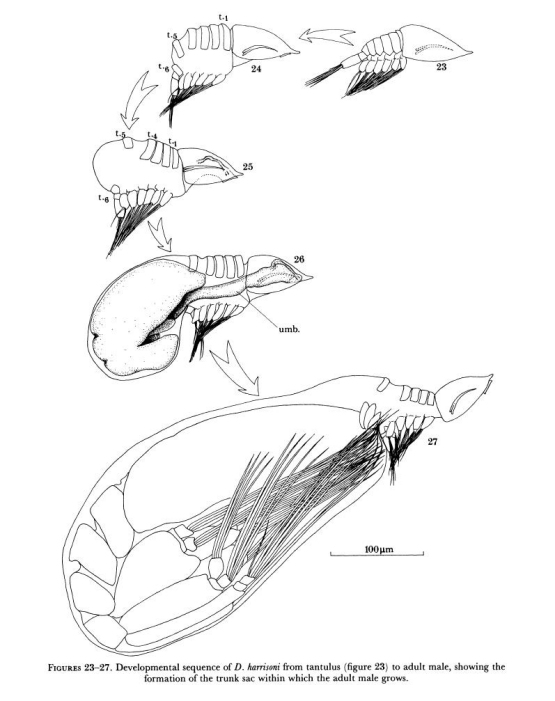

The obscure Tantulocaridans are thought to be a sister group to the barnacles, and include what are believed to be the tiniest arthropods on our planet. Their unusual "double life-cycle" begins when a tiny, segmented "tantulus larva" attaches itself permanently to another crustacean by its tiny oral sucker. This stage usually matures into an asexual female, a nearly featureless bag of eggs that will eventually burst with larvae.

Things get weirder in the sexual reproductive cycle, where larvae develop free-swimming males and females. That's not to say they develop into males or females, in the traditional sense, but rather, the larval body will swell into a bag containing the reproductive "adult," nourished by the larval head through an umbilical cord. We know that the adult bursts from the larval body and must swim away to find a mate, but to date, these adults have never been observed alive.

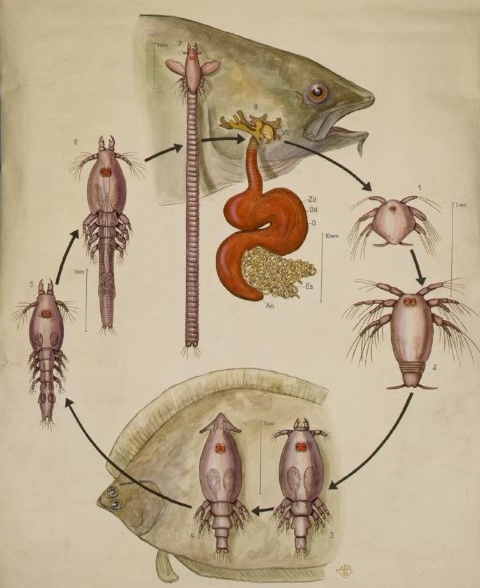

A number of copepod families within the Siphonostomatoida are collectively referred to as "anchor worms" or even "Lernaea" after the Lernaean hydra of Greek myth. By maturity, females lose virtually all recognizable crustacean anatomy, molting into slimy, worm-like or bag-like organisms anchored permanently in host tissues. Here, we see the beautiful booty of two Lernaeocera branchialis females dangling from their host's gills.

Humboldt University of Berlin

A bottom-dwelling flounder, sculpin or lumpfish serves as the intermediate host of Branchialis; a living singles club where a mobile male and female will meet. Bidding her lover farewell, the fertilized female will find herself a more active host species such as a cod, settling down permanently as she molts into her minimalistic adult form. Her elongated, branched anterior reaches deep into the host body and anchors in the bloodstream for a continuous food supply, while her slimy, bag-like body produces hundreds of eggs in tangled, noodly strands.

Salmincola is another Lernaean copepod, but with a somewhat different diet lending it an even more peculiar anatomy. The cluster at the top here is the non-living, tangled anchor it embeds in its host's skin, but a tiny mouth is situated on the end of the thick trunk to the right. Rather than draw blood or other fluids from within the host, this "head" is held outside along with the body and egg sacs, flexing about like an elephant's trunk to "graze" for the rest of its life on the same small patch of outer tissue.

Also featured in one of my Cracked pieces, Ommatokoita elongata is a possible candidate for the most disturbing of the anchor worms, though your mileage may vary when we get to our next one. This species embeds itself only in the eyeballs of the huge and powerful greenland shark, feeding on its vitreous jelly. Over 85% of these sharks are blinded in one or both eyes by these creatures, but can fortunately hunt just as effectively by the rest of their senses. Some have even speculated that the parasites attract prey to their hosts, but it's a controversial subject. Beneficial or not, you have to appreciate the sense of audacity in a tiny crustacean who evolved just to poke a shark's eye out.

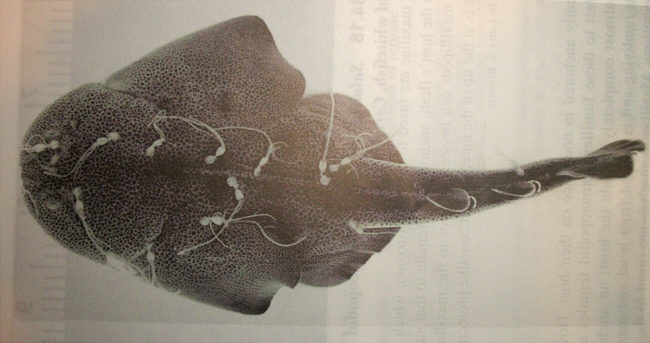

So just what could be worse than an eyeball-sucking sea louse, you wonder? Meet Trebius shiinoi of the family Trebiidae, embedded all over the embryo of an angelshark. Yes, the embryo. These sharks aren't egg layers, either; they give birth live. We don't even know how they get there, but mature T. shiinoi are found embedded in the uterine lining of certain female sharks, and will spread to the skin surface of unborn pups in pregnant hosts.

We've now looked at Crustaceans that attack the skin, eyes, lungs, anus, and uterus...where else would you absolutely never want a giant bug to grow? Your brain? Your genitalia? How about a two-for-one special?

A superorder within the barnacles, Rhizocephalans ("root heads") like the genus Sacculina begin their lives as a free-swimming "cyprid" like any other barnacle, searching for a place to settle down and grow. Unlike other barnacles however, said place is within the body of another crustacean, a living crab. There are several species attacking several different hosts, and in some locations nearly half of the crab population is infected.

Once the female cyprid locates a suitable victim, it inserts a thin needle into a seam of the crab's armor, injects a tiny clump of its own cells into the host and discards the rest of its body entirely, losing more than 90% of its total mass. Now little more than a protoplasmic blob, it begins to grow throughout the crab's interior almost exactly like cancer, wrapping fungus-like tendrils around organs, muscles and even the crab's eyes.

Soon, the intruder reveals its presence to the outside world as a bulging sac known as the externa, located where the host crab would normally carry a clump of eggs. If the host happens to be male, the parasite simply alters its hormonal balance until the crab is shaped like - and behaves like - an egg-carrying female.

It is at this point that the male barnacle finally enters the picture: Injecting himself into the externa, he fertilizes the parasite's eggs and the crab is induced to nurture them as it would its own, carefully cleaning and protecting the bag of baby barnacles. Eventually, the crab will climb atop a rock or coral and shake its body in the water's current, the same action normally used to release crab larvae. The crab will spend the rest of its life raising the offspring of this cancerous invader again and again, unable to ever reproduce with its own kind.

Source (PDF) and be sure to visit Parasite of the Day!

Rhizocephala may be among the world's weirdest parasites, but that only means Liriopsis pygmaea boasts some of the world's weirdest hosts. The featureless white globes we see here are highly degenerate isopods attached to the externa of a Rhizocephalan, in turn attached to its host crab. And just as the crab is castrated by its parasite, the parasite is rendered sterile by these hyperparasites.

Cymothoa exigua is one that many of you may already be familiar with; I first became acquainted with this marvelous monster from Carl Zimmer's wonderful Parasite Rex over a decade ago, and my ensuing blog post was once its sole google search result. As an increase in sightings brought its strangeness to news headlines, its internet fame positively exploded, and the "tongue biter," as many have decided to call it, is now probably one of the most infamous parasites in the sea.

The complete life story of a tongue-biter has yet to be unraveled, but we know that they initially enter their hosts through the gills, beginning as males but changing sex as they grow older. At her first opportunity, a newly female exigua climbs into the host's mouth and attaches herself to the tongue, draining blood through her front claws until the tongue gradually atrophies and disappears. Hooking her spiny tail into the remaining stump, the vampiric isopod can now be manipulated by her host as a fully functional new tongue.

Exigua was considered the first confirmed example of a parasite effectively replacing a host body part, but lest you think this makes the creature a beneficial symbiont, keep in mind that the fish was getting along perfectly well with a tongue that was not also a bug. These cute little bastards have been found in the mouths of over a dozen fish species from the gulf of California to Ecuador, and even turned up at least once in British waters. It's possible that these may in fact represent multiple species, but if so, they're virtually impossible to tell apart. How many tongue-eating sea lice could there really be? How many other undiscovered creatures may live their lives as prosthetic limbs? The tongue biter is hardly the weirdest, most extreme or most disturbing creature I've talked about here, but it certainly has a lot of unique charm - just look at those sweet little teddy bear eyes.

As you've seen, the ticks, lice, fleas and chiggers of the ocean depths come in a boggling array of forms, their taxonomy sometimes a nightmare to unravel and their life cycles often shrouded in mystery. Thousands of known crustaceans have turned to a parasitic life style, and evolution may have even stranger forms in store for the future.