| The Water Bears |

|

|

|

From the polar ice caps to the deep sea abyss, the phylum Tardigrada has conquered much of the planet Earth. They can endure temperatures from almost absolute zero to beyond boiling, emerge unscathed from a thousand times the radioactive bombardment of other known animals, survive over a decade without water and have even been exposed to the vacuum of space for days at a time, none the worse for wear. We would be fairly well screwed if we were talking about flesh-eating parasites, here, but these microscopic crawlers, often referred to as "water bears," are quite harmless to us humans, and preposterously adorable.

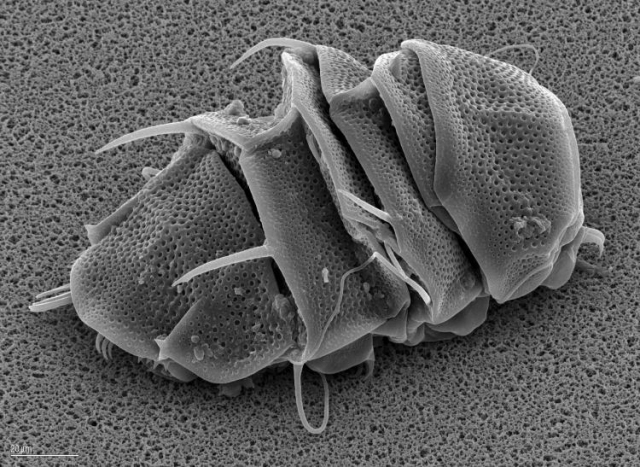

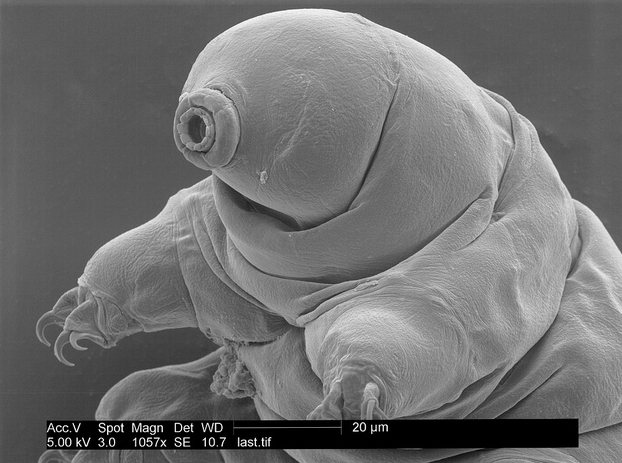

All Tardigrades possess eight stubby, tubular limbs, usually ending in very bear-like claws. They may or may not possess a pair of eyes, and lack lungs or any other respiratory system, their small size allowing gases to freely come and go from their bodies. Glands flanking a tardigrade's mouth secrete a substance which instantly hardens into sharp piercing implements, replaced with every molt and shaped according to the creature's diet, which I'll elaborate on shortly. First, let's talk about their famous nigh-invulnerability.

Photo: Dr. Ralph O. Schill

While a Tardigrade "naturally" lives less than one to three years, it may enter a state of cryptobiosis under harsh conditions, dehydrating into a dense, mummified husk called a tun. It is in this state of suspended metabolism that the animal can survive such a wide variety of hostile environments for many years at a time; with little water content, there's nothing in its body to form ice crystals, boil, or react to ionizing radiation. When the surroundings are more favorable, the tun plumps back up and the pudgy creature returns nonchalantly to business as usual. A tardigrade can "hibernate" and "revive" in this manner many times before dying, giving some species a hypothetical maximum lifespan exceeding a century.

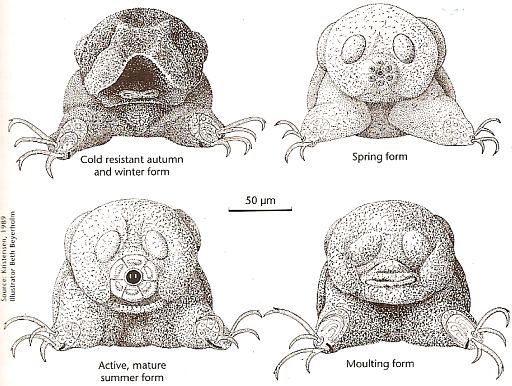

Some Tardigrades such as Halobiotus crispae also demonstrate cyclomorphosis, or seasonal transformations, molting into a thickly armored but still mobile winter form which may survive complete freezing for six months at a time. This species is a sea-dweller, but its spring form can tolerate fresh water produced as ice begins to melt.

The vast majority of tardigrada feed only on plant cells or bacteria, slicing them open and drinking their fluid contents. A few other species in tropical reefs even "farm" food from bacterial colonies in specialized cranial cavities. Some water bears, however, are a little less snuggly. Milnesium tardigradum shown here is one example of a fully predatory tardigrade. Moving incredibly fast on its first six legs, it employs its fourth pair only to stand upright and attack prey with the rest of its claws, not unlike an actual bear. Predatory species may also be adapted for leaping, rocketing at their quarry in the blink of an eye.

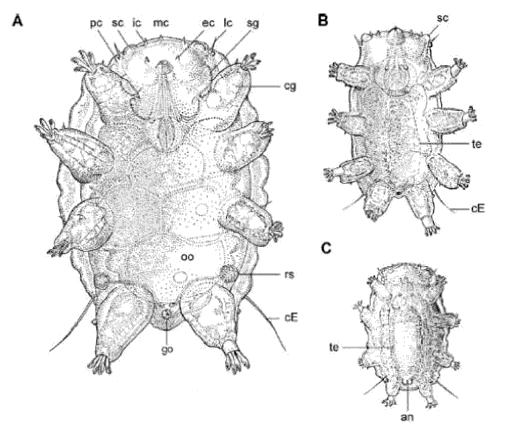

Other tardigrades are even parasitic. The species Tetrakentron synaptae is fully adapted to the outer body of the sea cucumber Leptosynapta galliennei, draining fluids from its epidermal cells. Females of this species (A) are flattened, tick-like and virtually immobile, their mouth situated beneath their domed bodies and their anus farther up their "back." Males, unusually, have been observed in two forms; slender, more mobile males (B) and nearly immobile "dwarf" males (C) who cluster around females.

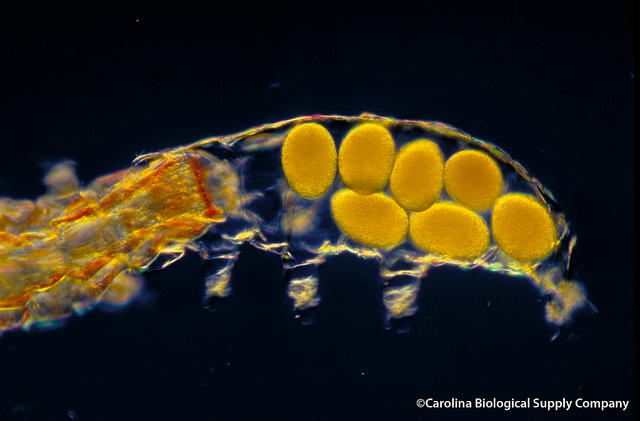

Courtesy Carolina Biological Supply Company

Reproduction methods may vary among species, but in traditional Tardigrade sex, the female sheds her entire "skin" with several large eggs inside, leaving the male to cover the hollow carcass in his sperm. By the time the eggs hatch, the young already possess the same exact number of cells as the adults, growing by the enlargement of cells rather than their multiplication.

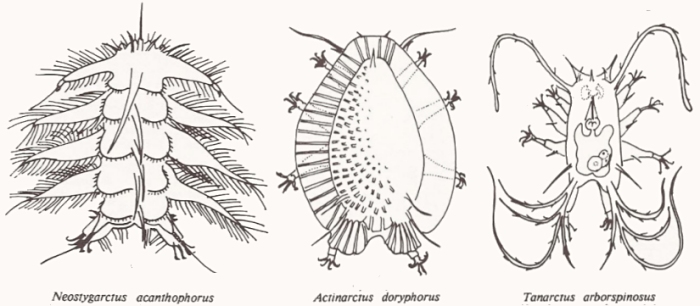

Tardigrade taxonomy has had a bumpy road; few were certain how to classify the little creatures until more recent genetic sequencing, which places them in their own sister group to the arthropoda and Onychophora. They bear some anatomical similarities to both of these groups and the nematodes or "roundworms," all of which are now considered members of the superphylum Ecdysozoa. I've barely demonstrated the mind-boggling diversity of these mighty survivors, only sparsely catalogued by the scientific world at all. There are tardigrades who live exclusively in the bodies of barnacles and tardigrades who live only in hot, toxic sulfur water. Nearly a thousand have been described by science and tens of thousands may yet exist, many of them bound to persevere through the worst that nature (and ourselves) could possibly hurl their way.

A closeup of M. Tardigradum. Source

|