The World's Weirdest CEPHALOPODS

Written by Jonathan Wojcik

You probably know by now that the Cephalopoda - squids, octopuses, cuttlefish and their other tentacled brethren - are intelligent, sophisticated mollusks with an arsenal of clever defense mechanisms, but the strangeness of this ancient group goes well beyond the common octopuses or the legendary giant squids.

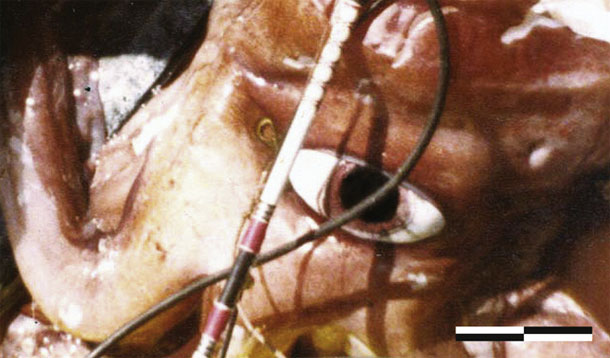

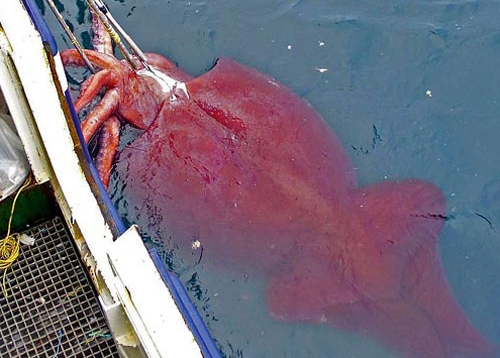

To kick this off with some of Mother Nature's original home brewed Nightmare Fuel, even I'm spooked by the cartoonishly human eyes of Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, also known as the "Colossal squid." Theoretically growing even larger than the famed "giant" squid, with shorter tentacles but much bigger, broader, bulkier bodies. these ferocious beasts hunt in freezing cold waters where they may prey on large fish and other squid.

More viciously armed than other giants, the suckers of a colossus are equipped with a variety of nasty claws, including the rings of jagged teeth present in other squid, unique swiveling hooks and these tough, three-pronged talons.

Terrifying though they seem, these titans are adapted in many ways for the safety of their young ones; thought to give live birth, females may retain thousands of eggs inside their massive mantles and even have a dark inner membrane to block out the luminous glow of the developing embryos, cloaking them from hungry whales and other dangers until they're ready to hatch.

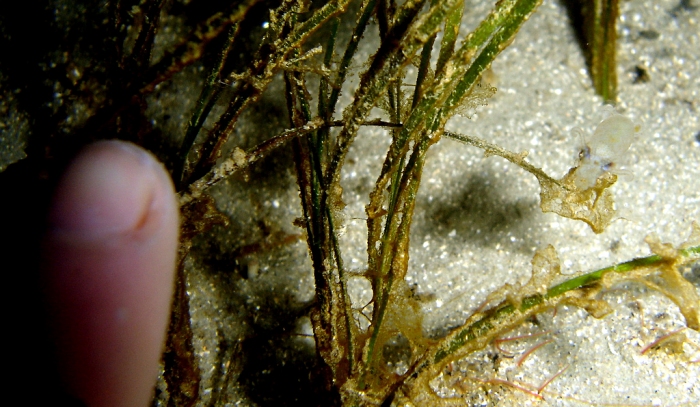

At the extreme opposite of the size spectrum, Idiosepius notoides is the tiniest known cephalopod, reaching an adult length under an inch. Adapted to warm, shallow waters, adhesive cells along their backs allow them to cling to blades of sea grass while leaving their tentacles free. Like insects in an aquatic meadow, they attach their eggs in rows to grassy shoots, the female keeping a close watch over them until they hatch.

In 2016, it was also discovered that pygmy squids like the related Idiosepius paradoxus deliberately squirt ink at their prey before attacking, which you can see in a video here. This was the first evidence that Cephalopods may also use ink "offensively," though this strategy has not been observed to really increase the pygmy squid's success rate; they're equally deadly to their tiny prey with or without an ink blast, or at least the prey that we've watched them hunt thus far.

Octopuses of the genus Grimpoteuthis earn the common name "dumbo octopus" for their comically ear-like, flapping fins, resembling a cross between the famous Disney elephant and a gelatinous umbrella. Dwelling in the dark and drably colored deep-sea abyss, they lack the advanced color-changing abilities of other octopods but may

confuse predators with transparency or bioluminescence. Instead of suckers, their thickly webbed tentacles are lined with hair-like sensory filaments called cirrae, which are thought to brush small particles of food toward their beakless mouth. Members of this group have been found at the greatest depths of any octopus, as deep as 23,000 feet below the sea's surface.

Once classified with the dumbos as species of Grimpoteuthis, the "flapjack" or "pancake" octopuses are now classified as Opisthoteuthis, though the initial confusion is understandable. The two groups have a great deal in common, though these little cuties tend to have a thicker mantle fusing the head and tentacles into one smooth, blobby dome, capable of stretching into a nearly flattened saucer-shape.

This flattening tactic likely helps to make the animal less conspicuous, both to predators and, perhaps, to prey, though their feeding habits have yet to be observed. If you ask me, as an armchair biologist with no formal education in a scientific field, their physiology strongly suggests a diet rich in Pac-man.

I hear you giggling.

It's easy for an octopus to camouflage itself amongst aquatic vegetation and colorful reefs, but

Amphioctopus marginatus frequents shallow, sandy waters where the monotonous scenery is often

only broken by the sunken shells of coconuts. By bunching itself into a tight, dark ball, it takes on

the appearance of this fallen fruit and "tip toes" away as though rolling in the current. The only

other species to demonstrate this bipedal motion is Abdopus aculeatus, which prefers to walk

around in the guise of seaweed. This is not, however, the only coconut-related defense by an

octopus...

When they're not role-playing coconuts themselves, marginatus species have also been observed

carrying one or both halves of an empty coconut shell in their suckers as a sort of armored "suit,"

one of the first recorded instances of tool use by invertebrates.

Totally transparent except for their eyes and internal shells, Cranchid or "glass" squid defend themselves by puffing up like a balloon and withdrawing their heads into their bodies like some wonderful squid-turtle-pufferfish chimera. Some species, like Cranchia scabra here, are even covered in tiny, thorny denticles to deter predators.

Similar species of Cranchiidae have their own distinct arrangement of spines, while some lack thorns

entirely. The adorable goofball above is a fairly recent discovery and a bit of an enigma, but may use

its polka dots in some way to confuse attackers.

When dredged up to the surface, it also seems to deliberately fill up its own body with ink. Rather than hiding within a cloud of it, then, they may use it to alter the appearance of their actual body against a darker backdrop.

Every year from March to May, Japan's Toyama Bay comes alive with the dazzling blue light of

millions, even billions of tiny bodies in the midst of a mating frenzy. While light production is hardly

unusual for cephalopods, Watasenia scintillans are thought to rely on it the most for

communication, and may be the only squid able to see in full color.

Millions of years ago, the seas were dominated by shelled cephalopods including both the subclass Nautiloidea and subclass Ammonoidea, known to reach tremendous sizes. Only the nautiloids survived complete extinction, and are represented by only six species alive today. During daylight hours, they rest in rocky crevices, shelled side out, between 100 and 300 meters deep. Every single night, they ascend to nearly the surface to hunt small fish and crustaceans. They can nonetheless survive for months without food, and are known to live for up to 20 years - literally ten times longer than most other cephalopods. This slow metabolism is due in part to their energy-saving method of locomotion; gases exchanged between the hollow chambers of the shell allow the animal to easily adjust its own buoyancy.

These ancient creatures have more primitive, sucker-less tentacles than their relatives, but may

have over ninety at any given time. They not only prey on small animals but will scavenge the

discarded exoskeletons of recently molted crustaceans, maintaining healthy growth of their own

shell.

Found off the coast of Australia, the four species in the genus Tremoctopus are known as "blanket" octopuses for the female's unique defensive mechanism; a long, billowing membrane of skin she can unfurl like a cape as she soars majestically away from her attackers. In addition to making her appear larger and more threatening, the cloak serves as an effective decoy, easily tearing away without harm to the animal.

Amazingly, the males of this genus were only identified in the early 2000's, thanks to being less than a hundredth the size of the female. After pumping a specialized penis-like tentacle with sperm, the little guy snaps off the appendage in the female's body and dies shortly afterwards.

Before developing their parachute trick, young females as well as males are often seen hanging closely around the toxic Portuguese Man O' Wars for protection, immune to their paralyzing and agonizing venom. When startled, they may frantically tear apart one of the jellies to create a deadly cloud of stinging tendrils, or simply carry a piece with them as a biological weapon.

Left: Mbari Right: Tolweb.org

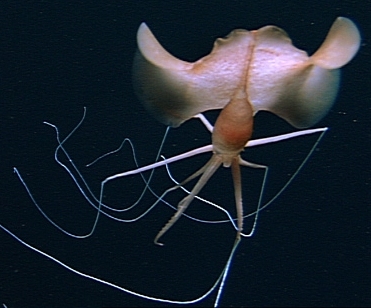

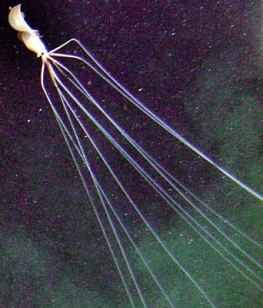

Observed for the first time in the late 80's and again in the early 2000's, this poorly understood deep-sea phantom represents the genus Magnapinna, once known only from dead juveniles. Sometimes known as an elbow squid or a bigfin squid, it does indeed have curiously "elbowed" tentacles that sharply bend before they trail nearly twenty feet from its broad, big-finned body, probably to spread them out a little more and keep them from tangling together as they dangle in the water more like the tentacles of a jellyfish. It's likely that the animal simply drifts in place, waiting for prey to bump into its tripwires, but we aren't entirely sure just what it eats. What we do know is that the tendrils are extremely stretchy; stretchier than any other Cephalopod tissues, and could possibly reach out behind the animal as far as forty feet, or twelve meters to all you other countries out there.

As much adoration as I have for all of these animals, I also have to admit a certain nagging, but deeply satisfying sensation of existential dread when I look at images like these; to contemplate pale, alien shapes adrift in the weightless darkness of the deep, inhuman thought behind lidless, glassy eyes as they grope for equally alien prey, makes for imagery both hauntingly beautiful and positively bone-chilling in a fascinatingly primal way. I'm not sure that poor little Lovecraft could have handled knowledge of the long-arm squid, but I really like to just think about the fact that thousands of these are down there even now, just hanging in the dark like that.

Members of the genus Histioteuthidae or "Jewel squid" have also been referred to as "cock-eyed squid," for in all known species the tubular, bulging left eye is at least twice the diameter of the flat, sunken right eye. Such extreme asymmetry between visual organs is almost unheard of in other animals, so of what use is it here? The answer is interestingly complicated.

In the perpetual night of the deep-sea abyss, predators may be so sensitive to light that solid objects still stand out darker against the faint remnants of sun that trickle down from above. To protect itself from such discriminating senses, the Jewel Squid practises what is known as bioluminescent cryptis - producing just enough light of its own to eliminate the contrast. They light up to blend in with darkness, a trick that would never work up here on the relatively bright and shiny surface world.

In order to keep track of how brightly they should glow throughout the day, that specialized bug-eye

is constantly aimed skyward and finely tuned to the rays of our yellow sun. Additionally, this makes

the blue or red lights of sea creatures stand out like a sore thumb, thwarting any predators that

employ their own cloaking system. Its other, smaller eye, directed downward, scans for tiny fish and shrimp

that might make a good meal.

Members of the Decapodiforms, the clever and curious Cuttlefish rival even the octopuses in their mastery of color, even animating patterns on their bodies to confuse and mesmerize simple-minded prey. Perhaps the most colorful of all, however, is Metasepia pfefferi, looking more like some sort of orchid than an animal. This intense pattern has been confirmed in recent years to warn predators of its highly toxic flesh, making it one of only three poisonous cephalopods known to man.

Stranger still, Flamboyant cuttlefish can't float quite as effortlessly as other decapod mollusks, and spend much more of their time walking along the seafloor with a quadrupedal gait, two muscular skin-flaps serving as "hind legs" while its outermost pair of arms act as forelegs. It feels almost unnatural to watch a tentacled mollusk crawl around in such a vertebrate-like fashion, though it's far outweighed by the sheer preciousness of those little tenta-footies. It's stepping! What kind of cuttlefish steps!?! That's silly, Flamboyant cuttlefish!

Spirula spirula

The "Ram's Horn Squid" is the only living species (as far as we know) in the entire Cephalopod order Spirulida, and the first time a living specimen was ever observed in its natural habitat, let alone filmed, was only in 2020. It's a wonderfully chunky little squid, too, with short, webbed arms, large eyes, and flimsy looking but effective fins encircling the opposite end of a perfectly burrito-shaped body. Their existence was known for centuries, however, not only from the occasional dead body but from the coiled, internal shells completely unique to their order:

Filled with hollow chambers, this pale little coil floats to the surface of the sea when it works free from its owner's decaying remains and frequently finds its way to beaches, the only spiraling shell possessed by any modern Cephalopod other than the Nautiloids, but much closer in appearance to their distant, extinct Ammonite cousins.

Spirula is also unusual in having a single, very large, bright green light at the end of its body, between its fins. The purpose of this light was the subject of much speculation until the first live observations; now we know that, like the many tinier lights of the cock-eyed squid, the glow is pointed downward to counter-shade the creature against the lighter sky.

Taningia danae is one of the largest squid, even if it's not "colossal," and gets its common name from the fact that it has only eight limbs, all roughly the same length. Personally I'm more stricken by the fact that their short limbs and big, broad fins can give them an almost stingray-like shape, though there aren't any photographs with their fins completely spread out. What stands out most of all about this sea monster however would have to be the fact that two of its arms end in the largest light-producing organs ever discovered in nature, often compared to the size and shape of your average lemon and intensely bright. In the 2010's, these squid were finally filmed hunting in the wild, and it was found that they rapidly "strobe" these lights as they attack. The lights are weapons, blinding and disorienting their prey, maybe even stunning sensitive enough creatures. Think of the eye pain and dazing effect when you go instantly from total darkness to a bright light in your face, and now imagine there's a carnivorous spaceship attached to those lights, with a beak that can cut through bone. NEAT.

The Seven-Armed Octopus

I somehow never knew about this until very, very recently, almost the 2020's! Or maybe I'd learned a little about them, but other Cephalopods crowded out the information? They certainly don't come up often, which is terrible, because they're truly odd and unique giants. Reaching from nine to eleven some feet in length (three meters or more), they can nearly rival the length of the Pacific Giant Octopus, and they're significantly CHUNKIER, too, a massive cannonball of a mollusk! The common name refers to just the male, whose reproductive arm is reduced and kept coiled inside a pouch, though both sexes have a strange arrangement in which the rearmost arms are the longest, with the frontmost pair being relatively nubby for most octopods.

While I haven't seen anyone else put it this way, I think the most interesting thing about these beasts is that they seem to be the Cephalopod answer to the "Ocean Sunfish" Mola mola, or I guess mola are the bony fish answer to Haliphron? Both have adopted a lifestyle of casually drifting on the hunt for a diet of primarily jellyfish. And like multiple other creatures on this page, they too will carry around a jellyfish or part of a jellyfish for the defensive bonus of the stinging cells. How wonderful is it to think about these big, white, gloomy-eyed, ghostly-pale blobs just slurping up jellies in the dark, as we speak?!

Literally meaning "Vampire Squid from Hell," this seldom-seen haunter in the dark is the only living species in its ancient order, Vampyromorphidae,

believed to have been larger and more abundant during the mid-Jurassic period before gradually retreating to the protective darkness of the abyss. Adapted to expend as little energy as possible, they are among the few complex animals comfortable in Oxygen Minimum Zones or Shadow Zones, areas of poorly oxygenated, effectively stagnating seawater.

Moreso than any other deep-sea cephalopod, Vampyroteuthis defends itself with a devilish array of light tricks; like the Jewel squid, tiny photophores speckle its body to counteract ambient light. Brighter lights on its tentacle tips can give the impression of a whole school of smaller organisms, and the massive, lidded "headlights" at the end of its mantle can give it a larger, more threatening appearance or the false impression of retreat as they shrink and close off. When all else fails, it may flip its entire "umbrella" inside out, becoming a dense, prickly-looking grey ball to confuse animals who thought they were chasing some sort of squid a moment ago.

As though it couldn't possibly get any odder, the vampire squid's feeding habits were only finally deduced in 2012 by researchers at MBARI. Long assumed to feed on small crustaceans, analysis of specimens in both the field and the laboratory revealed that the so-called "vampire from hell" has quite possibly never harmed one hair on another living thing. While every other cephalopod known to man is a strict predator, these phantoms feed entirely on globs of decomposing organic waste known as marine snow. Extending one of those unique, stringy filaments, they trap tiny particles of detritus in rows of nearly microscopic bristles, scrape it off in their tentacles, coat the nutritious refuse in mucus and ferry it to their soft, toothless mouths with their finger-like cirri; the sea's most elaborate and frightening looking garbage disposals. Beautiful.

Grimalditeuthis - the "Fishing" Squid

We love an aggressive mimic around these parts, and are you even surprised at all to learn there's such a thing as basically an "anglersquid?" Plenty of Cephalopods likely use lights and tentacle tips to attract prey, but Grimalditeuthis bonplandi has exceptionally long whips whose sucker pads are shaped like smaller squid, complete with their own flapping fins. Of all the animals I can think of with some sort of mimetic lure, this is one of the only creatures whose lure resembles a tinier version of its "own kind."

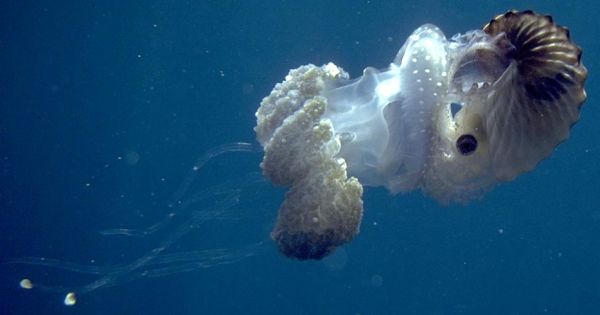

Closely related to Tremoctopus, female "Argonauts" are only ten to twenty times larger than the

males but far stranger in appearance. Unlike any other genus of octopus, females are able to

construct a shell-like egg case remarkably similar to the true shells of their ancestral ammonites.

Secreted by a pair of highly modified tentacles, this calcerous, papery structure gives the

animal its common name, "paper nautilus." A bubble of gas gives this false shell buoyancy, and the

mother faces outward to ward away predators with her venomous bite. Bizarrely, some species

have been seen attaching themselves to the tops of live jellyfish, possibly feeding parasitically off their

gastric contents and adding an extra layer of defense to their mobile nursery.

So, if it's a totally different process with totally different materials, why does the egg case of this octopus so closely resemble the interior of an ammonite or nautiloid shell? While it could very well be a case convergent evolution, it's also been theorized that these creatures once carried the old shells of other mollusks in the manner of a hermit crab, and secreted the "paper" shell as a lining for these borrowed homes. After most of the shell-bearing cephalopods went extinct, the secretion may have continued to be useful as an egg case.

There are many animals that closely resemble other, more dangerous creatures as a defensive

mechanism, but the indonesian Thaumoctopus mimicus is the first animal ever discovered to

imitate both the appearance and behavior of many different species for different situations.

Here, a mimic octopus creates a false sea snake by taking on its

coloration and hiding all but two tentacles. This is often employed as a

defense against damselfish, which sea snakes have been known to hunt.

By flattening itself and skimming swiftly along he seafloor, the octopus

takes on the appearance of a flounder, a fish that the mollusk's

common predators might find distasteful.

Another handy disguise is that of a Stomatopod or "Mantis Shrimp" - these crustaceans are well known to man and animal alike for the incredible power of their bladed claws, capable of shattering glass or snipping through bone.

This is just a small peek at the mimic's bag of tricks. Over a dozen imitations have been observed in a single specimen, and many more may yet be discovered. By rapidly changing both its form and direction, it easily fools predators into thinking they've lost track of their prey, and its preferred murky waters make the difference even tougher to spot - tough enough that the species eluded human notice until the their formal discovery in only 1998.

Sadly, this incredible creature may already face extinction through poaching - due entirely to the prices they can fetch in the exotic pet trade. They are short lived in captivity, many more die in transit and captive breeding is thus far unheard of. Hopefully, populations of these dopplegangers may persist in still-unexplored regions of the tropical sea, and many more species may still await discovery.

Perhaps someone you know has been an octopus all along...

Perhaps everyone but you.