Written by Jonathan Wojcik

Like the gastropods, cephalopods and bivalves, chitons are their own distinct class of mollusk, the Polyplacophora, but their appearance almost calls to mind the long extinct Trilobites, with whom they shared Cambrian seabeds roughly five hundred million years in the past.

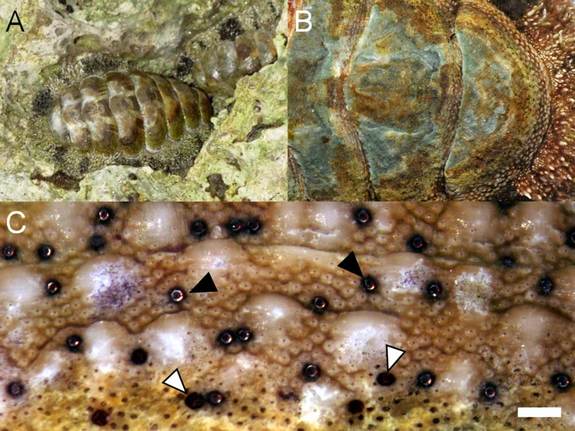

Unlike any other mollusk, a chiton's shell is split into eight articulated, overlapping plates along their upper surface, which allow many chitons to curl up into armored balls like certain armadillos, isopods or Samus Aran. Encircling and sometimes even covering the shell is the mantle, which can cling like a large and powerful suction pad to smooth rocks and other surfaces. In some species, the mantle is even coated in dense spines (above) for added protection.

Image by D. J. Eernisse © 2009

Like many of their gastropod cousins, chitons typically feed by scraping algae into their throats with a tooth-covered "tongue" or radula, though some chitons have adapted to more divergent dietary preferences. Placiphorella velata is an example of an actively predatory chiton. With its enlarged mantle held aloft, it makes an attractive shelter to smaller animals - a place to hide from predators. If they disturb its sensitive tentacles, however, their shelter collapses over them, pinning them down as the chiton chews its way through their flesh. The same "murderous cave" technique is also employed by certain echinoderms.

The largest chiton known to man is Cryptochiton stelleri at up to fourteen inches in length, often called the "gumboot" chiton and referred to by some beachgoers as "wandering meatloaf." The shell in this slablike blobster is covered over in a layer of skin, making the animal a sort of flabby, featureless lump that delights me more than it probably should. What I wouldn't give for one of these in a saltwater aquarium - and nothing else. Just a big, meaty wad I can name and nurture and eagerly introduce visitors to.

Unusually, the "teeth" of a Chiton (lining its tongue-like radula) are composed of magnetite, the most magnetic of all natural minerals. This could be what gives chitons such a remarkable sense of direction, as many species return to the exact same resting place each and every day, wearing a perfect chiton-shaped mark or "home scar" on a rocky surface. These highly magnetic inorganic teeth are found nowhere else in the animal kingdom, and they aren't the Polyplacophora's only unique adaptation...

As swimming larvae, chitons bear a normal pair of tiny eyes, but lose them completely by adulthood. This does not mean, however, that all chitons are completely blind. As recently as 2010, biologists have deduced that small nodules of the mineral aragonite in chiton shells can detect light, movement and possibly even pick out shapes. Essentially, some chitons "see" through dozens of eyes made of what is more or less "rock" embedded in their armor, evolving their own original visual equipment unlike that of nearly any other organism.

Kirt L. Onthank

They're armored slugs from the dawn of time, with stones for eyes and magnets for teeth. We're lucky they're so slow, small and harmless - I'm pretty sure they only exist as a stern warning to us all of what mother nature is capable of.