CREEPY CLASSIC DRAGONS

Written by Jonathan Wojcik 3/17/2013

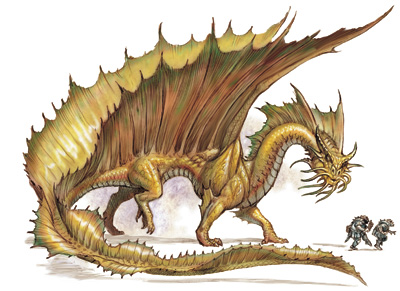

In most modern fantasy scenarios, the word "dragon" often entails a creature of raw, awe-inspiring power. Some are noble, benevolent, even intelligent beings, unfairly demonized by foolish little man-things. Others are savage yet magnificent embodiments of nature's brutality, dazzling behemoths to whom humans are like so many nuggets of squealing meat. They're symbols of might, ridden through hurricanes by naked warrior princesses with flaming swords.

They're trying a little hard, aren't they?

It's the same sad fate that has befallen vampires, fairy-folk, mermaids and the once flesh-eating unicorn; what originated as a frightening, grotesque abomination of nature has been romanticized to the point that it's barely even categorized as a monster anymore. How often do you even hear the term used to describe a dragon? They've been elevated to a category seemingly "above" monstrousness, to almost god-like fantasy animals. Now, don't get me wrong; the dazzling Heavy-Metal-album new-age dragon has its place in popular culture and can be executed in a lot of sincerely cool, fun ways, but it just seems a shame to completely discard the western dragon's grungier, ghastlier past. Time for an art lesson!

Painted in the 1430's, Rogier van der Weyden's Saint George and the Dragon was a fairly typical interpretation of the famous legend; the dragon here is a far cry from the golden-scaled behemoths we're accustomed to today. It's not big. It's not glamorous. It's definitely not something most kids wish they could be when they grow up. It's downright pitiful, in fact. Just look at those pleading, beady eyes:

Values have come far enough that most of us probably only feel sorry for this poor little guy; it only looks small, frail, terrified and helpless. A maiden in no apparent danger stands idly by as a "brave" knight bullies an endangered species. In the 1400's, however, dragons like these were seriously - and successfully - intended to invoke revulsion and contempt in the viewer. Bear in mind, it wasn't long ago that compassion for animal life would have been considered some sort of mental illness, and before then, a symptom of paganism and witchcraft. Animals that weren't immediately useful in immediately obvious ways - lizards, toads, venomous snakes, bats, rats, insects, basically the majority of life as we kow it - were seen as nothing more than detestable, unclean vermin, sometimes even regarded as unholy, arising somehow outside the Judeo-Christian God's creation plan.

It's not all that surprising, really; nobody had a concept of ecology, of how diseases worked, of why exactly one bite from the wrong snake could kill a precious workhorse, and mere mice could mean the difference between a healthy harvest and a family starving to death. We look at this painting and see an innocent little snake-chicken-possum abused by a heartless barbarian, but when it first went on display, people saw a righteous hero ridding the world of another obscene affront to the natural order.

And that's a lot more interesting to me than a dragon people want to be.

Here's another one, painted by Bernat Martorell in the very same decade. His dragon is at least armed with forelimbs and fangs, but it's still a small and scrappy looking mongrel; a little doglike, a little ratlike. The tail almost resembles the tentacle of an octopus, though it's hard to say if Rogier would have ever seen a cephalopod. The strangely hooked nose is interesting; I can't even think of an animal that might have come from. It's a little easier to imagine this one as a product of "evil," since it could at least conceivably tear apart human flesh.

Paolo Uccello's 1470 take on the same legend features a bigger and more menacing beast, though the look in its face is one of pure submission and misery. The supposed "damsel in distress" also seems to have things pretty much under control on her own; I swear she's just casually describing it as she leads it on a leash for Saint George to stab through the face. Brutal. The eyespots on the wings are an interesting feature, since they keep reappearing in many other Saint George paintings. These artists would have likely only seen such patterns on the wings of moths and butterflies.

32 years later, Vittore Carpaccio painted one of the darkest and most gruesome depictons of Georgie's victory, his utterly wretched dog-like dragon prowling a blighted and pestilent landscape, littered with the mutilated remains of past prey. Still no glittering treasure hordes, here; only half-gnawed corpses and severed, rotten heads.

Similarly grim is Giorgio Vasari's vision from 1550. It's over a hundred years newer than most of our prior examples, but the concept of the dragon hasn't changed that much; this shaggy, donkey-eared, turkey-legged mutant still has a mostly sorrowful, pathetic countenance, only adding to the horror of that positively haunting human carcass. This is a dragon that looks like it would never stop crying...while it chews your skin off and wolfs down your entrails in a cavern thick with stinking carrion and feces. You can almost root for this one's death just because it looks so anguished to exist at all.

We're going to finally give Saint George a rest to look at just a couple more draconic nightmares, not the least of which is Hendrick Goltzius's portrayal of Cadmus avenging his fallen companions, slaughtered by what has to be one of the most terrifying dragons we'll have looked at here. Those unblinking, glassy fish-eyes and convoluted facial scales look quite unnatural on its slightly emaciated, mammalian body, and even under attack, at least one head just keeps gnashing gluttonously at the bloody remains of what was once a man's head. This is not a sympathetic dragon, intentionally or otherwise. It has a mindless, alien hunger and really feels like it shouldn't be.

Ironically, this image of Saint Michael slaying what's apparently Satan himself in "dragon" form may be the most heart-tugging dragon since our first. How can you look into those gigantic, watery eyeballs, eyeballs remarkably similar to those of a damselfly, and not want to pat the little Nemesis of All Mankind on his little fuzzy head? I haven't had much luck finding the artist behind this one, their name quite possibly lost to history; it's another from around 1440, appearing in the Book of Hours manuscript. Dragons were quite often considered interchangeable with the devil, though this diabolical "dragon" lacks even wings, an elongated neck or any other features that have now become rather stereotypical of the creatures.

Another image I'm having difficulty researching or properly attributing, these might be my favorite medieval dragons yet, the only ones I've ever seen covered in eyes. With eight legs, curly tails and two snapping heads, I could almost believe these are gross misinterpretations of huge scorpions, which wouldn't even make them the most inaccurate medieval paintings of real animals at all. I also appreciate how every head is wearing a crown. All of them are the king and queen.

The very last dragon I want to bother you with comes from none other than good old Salvador Dali. It's another "Saint George and the Dragon" painting, but as recent as 1942, and still giving us a downright nightmarish monstrosity, colorful yet sickly, more an obscenely distorted hell-turkey than a purely reptilian fiend, not that George's horse is any less unsettling. Less than a hundred years ago, unnatural and gruesome dragons were apparently still popular...so, what happened?

I suppose it's understandable that after centuries of twisted, diseased, maiden-gnashing rat-lizards from the pits of hell, people would grow tired of the concept. Sometimes borrowing from the superficially dragon-like beings of very different cultures, the modern dragon can still feature as a formidable villain, but when it isn't an ass-kicking power fantasy, it's a cute sidekick to wizards and talking ponies. Dragons now almost invariably aim to be admirable, even when they're the antagonists, and while it's certainly nice that giant reptiles are no longer typecast as abhorrent, I sometimes feel like we've gone a bit too far in the other direction. I miss the abhorrent dragon.

Nothing is wrong with the majestic, endearing sword & sorcery style dragon, no; I've enjoyed plenty of them over the years. I just think there's still plenty of room in our popular culture for the kind of dragon that scrabbles and skulks, belching noxious fumes from its stagnant swamps and filth-smeared tunnels. Dragons are still played for suspense, but never horror anymore, and I think their grodier, less glamorous past demonstrates how much potential they have always had, and should still always have, to fall squarely into the monster category.