Written by Jonathan Wojcik

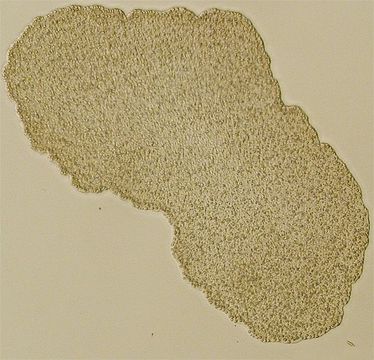

Discovered in 1883, the enigmatic Placozoa (literally "flat animals") are a distinct phylum of animal life with only a single recognized species, Trichoplax adhaerens, though there seem to be a number of different species indistinguishable above the genetic level. They seem to be almost nothing but tiny, featureless scraps of living flesh, but there's a little more to them than meets the eye.

Unlike most multicellular animals, Trichoplax has no true tissues, organs or any set shape; only four types of cells arranged in an irregular three-layer sheet, so thin it can be almost invisible in direct light. The outer cells are similar to those lining our own internal organs, and sport wriggling cilia to propel the animal over surfaces or even "swim" in open water. Floating loosely within this membrane are three other cell types and usually a number of symbiotic bacteria.

These squirming scabs are surprisingly complicated when it comes to reproduction, with three different ways to perpetuate themselves: most commonly, they simply split apart into multiple fragments, having no distinct body parts that need to be duplicated. Less often, a young one will slowly "bud" from its parent, beginning as a small ball of all four cell types. Rarely, a Placozoan will develop an "egg" inside its body, transforming itself into a protective envelope which will degenerate and die to release its offspring. This is believed to be the result of sexual reproduction, but "mating" has yet to be observed.

While a Placozoan has no front, back, left or right, its "top" and "bottom" surfaces differ in an extremely bizarre manner: each side has its own method of feeding. The lower side, which bears denser cilia for walking, encloses food particles and releases digestive enzymes, essentially forming into a temporary external stomach. The upper side, however, is able to prey on single-celled organisms by trapping them in a layer of slime and pulling them through the spaces between its cells, right into the animal's fluid interior. It would be as if you could unzip your stomach and simply place your meals inside.

Genome sequencing suggests that these mobile smears of life-stuff have been sliming around our seas for quite some time, and have more in common with rest of us animals than you might expect; all the genes necessary for a more complex body and nervous system seem to be there - and in a similar order to us humans - but the little guys just haven't needed them and don't express them. They've got all the windows software, but they're still only working in DOS... and it's served them well.