Written by Jonathan Wojcik

Imagine if you were nothing but a limbless, nearly brainless head and torso. Unable to move, you would nonetheless travel quite far as your body multiplied, like stalks of grass, into hundreds of thousands more torsos, loosely connected by their intestines and a few nerves. Most of your biomass would spend its time eating whatever it could catch in its many mouths. Other parts of you would be little more than heads with grossly disproportionate jaws, sprouting off your many backs to ward off attackers. Some of you might be male and some of you might be female, eventually mating with yourself and birthing fully mobile infants. These would crawl away until they found empty fields of their own, discard their limbs and begin to copy themselves just like you.

This is all quite normal for the Bryozoa or "moss animals," tiny creatures that have flourished since the early Cambrian in every aquatic environment imaginable, from freezing arctic trenches to stagnant pools of filthy sewage. While individually tiny, they can replicate themselves to blanket large areas - hence "moss" animal - or construct a variety of elaborate structures. Some grow into beautiful, branching "trees" and "bushes." Others form massive, gelatinous blobs. Some drift in the ocean as tiny spheres, and some form small clusters that can crawl on a slug-like foot.

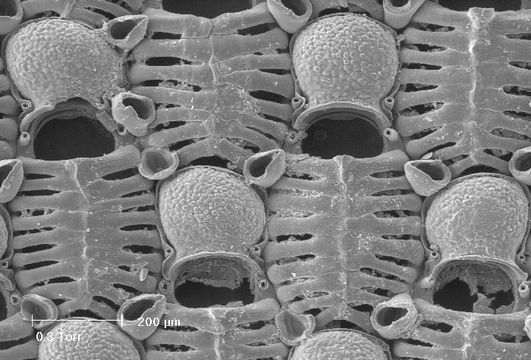

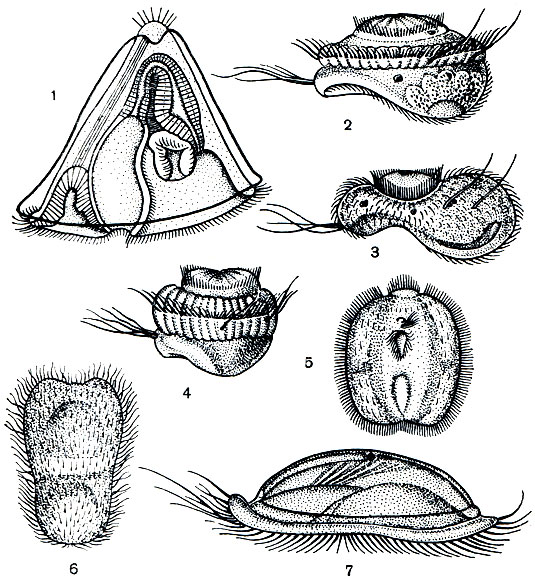

Individually known as zooids, the many bodies of a moss animal are contained in densely packed exoskeletons with a variety of possible shapes. Some are tubular, some are perfect six-sided "bricks," and some apparently look like walls of dead turtles. Just under the skeleton is the animal's rubbery, bag-like body wall, and within this, the Polypide or main body. Interconnected to share food and genetically identical, the zooids are neither truly individuals nor truly a single being, but can come in many strange, specialized forms.

The autozooid or feeding body is a bryozoan's bare essential, distinguished by a polypide with a protruding, tentacle-ringed mouth. Organic particles contacting the tentacles become trapped in mucus, and are ferried down into the pharynx by rows of waving cilia. The simple, u-shaped gut loops back up into an anus almost directly beside the mouth, a step up from the unrelated but vaguely similar corals and anemones, whose mouths are also anuses. Eventually, an autozooid must discard its polypide, leaving only its still-living body wall to regenerate a new animal. In some species, single-tentacled nanozooids are rapidly grown to fill in for zooids busy regenerating or the permanently deceased.

Some bryozoans produce kenozooids, largely empty bodies with just a few strands of living tissue. These living building blocks form the stems of stalked and branching colonies or even "chimneys" to pump away water the autozooids have already filtered. Encrusting colonies may also grow these hollow dummies just to claim more territory at a faster pace - especially if they detect another bryozoan colony encroaching on their turf. This aggressive expansion happens even faster if the rival is a species with smaller zooids, though we're not quite certain how these bullies can tell.

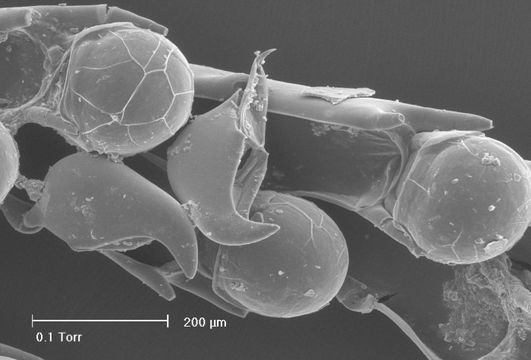

As if you weren't excited enough by lego blocks that poop on themselves, some bryozoans produce snapping, claw-shaped defensive bodies called avicularia. Likened by Charles Darwin to the heads of tiny vultures, these fanged warriors snap shut on attackers such as sea slugs or tiny crustaceans, even chomping small enough foes into pieces. The fearsome "beaks" are formed by their tough outer body walls, with the inner body reduced to a sensitive triggering mechanism and fully dependent on food from neighboring autozooids.

Some species grow avicularia the size of entire autozooids, while others mount smaller snappers to the autozooids themselves; here we see a pair of these defensive sentinels growing like crab's claws on the cage-like exoskeleton of a Cauloramphus autozooid. In the beautifully named genus Bugula, these zooids are even mounted upon swiveling "necks." Many colonies hold off on producing defensive zooids unless predator activity begins to increase, but can finish growing a beaky phalanx in under 48 hours.

British Antarctic Survey

Cloning is all well and good to grow a colony, but for a colony to make new colonies, it needs to have some kinky, colonial invertebrate sex. For many bryozoans, zooids are simultaneous hermaphrodites and self-fertilizing. For others, zooids change from male to female as they grow, males releasing sperm from their tentacles to be trapped and swallowed by the older females, which my buddy told me is good for their skin. In some species, the mother will break down her internal body as food for her young, while others produce special gonozooids who function as living brood chambers.

The swimming or creeping larvae can take a variety of shapes. Most are born with a large food reserve and immediately search for a location to settle down, but some species bear cone-shelled cyphonautes larvae, who spend more time in their mobile stage and can actually feed themselves.

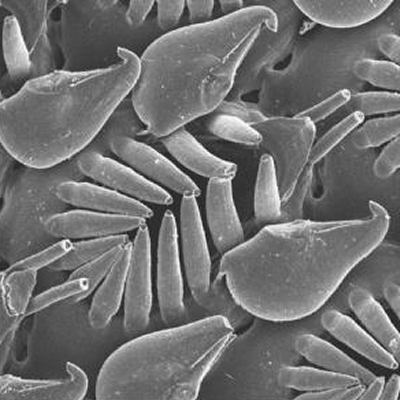

Like their possible cousins the rotifers and the unrelated tardigrades, freshwater bryozoans have a bizarre trick to surve inhospitable conditions; an armored capsule called a statoblast. Just like the seed of a plant, the statoblast comes packed with a food supply for the tiny larva and can resist drying or even freezing for extended periods of time, "hatching" into a new feeding zooid (above) when it finds a safe place to grow. Some statoblasts are even coated in sticky hooks, clinging to other plants or animals and spreading to new bodies of water.

While they may seem like the animal kingdom's answer to bread mold, Bryozoans have been thriving on our planet for nearly half a billion years, and are showing no signs of decline anytime soon. What little they do as they sit silently in their own skeletons, it works, and perhaps we have a thing or two to learn from their enduring success...