Written by Jonathan Wojcik

The ancient Neuroptera or "net winged" insects include some of Insecta's weirdest, fiercest and most specialized predators. Their delicate, beautiful adult forms a far cry from their fanged, monstrous and insidiously devious larval forms, though in many cases, just as deadly!

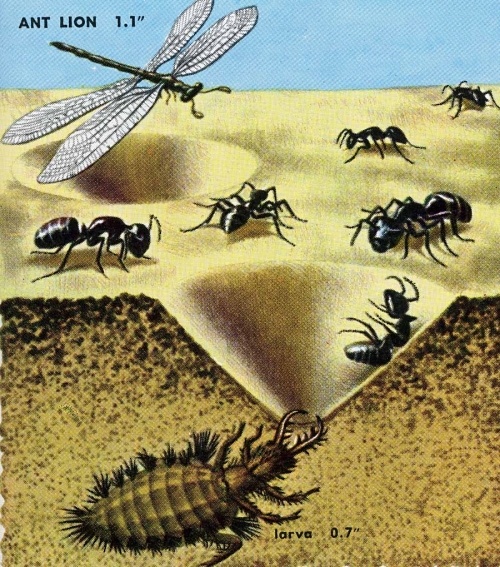

By far the most popular of the net-wings are the Myrmeleontidae, better known as antlions. The short lived adults, who may be herbivores, omnivores or predators themselves, closely resemble small damselflies with more prominent, club-shaped antennae. Though still quite small, these particular insects demonstrate the most extreme size difference between the larval and adult body, stretching their mass almost literally to the breaking point with an incredibly thin, fragile adult exoskeleton.

It's during the larval stage that antlions earn both their name and their fame, also known in some places as doodlebugs and in Japan as ant hell. The hairy, hunch-backed beast typically lies at the bottom of a conical pit in dry, fine soil or sand, preying upon unwary insects who stumble to their doom. This death trap is constructed as the insect scuttles backwards in an inward spiral, using its forelegs to scoop sand onto its shovel-shaped head and flinging it away with a flick of its neck. It continues this repetitive action until sand no longer slides back down into its face; a single, reflexive response to a single, simple stimulus which ceases on its own once the pit can hold its shape.

It obviously doesn't take much to disturb this minimal stability, and when the tiniest insect slips and falls into the crater, more sand tumbles to the bottom. The monster returns to its scooping, flicking and hurling, only now, this action pelts the victim with debris and pulls it deeper to its death. When it touches the antlion's jaws, they snap shut like a fox trap, and the buried monster takes a break from digging to enjoy its meal. The tusk-like jaws are a fused combination of the mandibles and maxillae, pumping venom and digestive enzymes along their inner grooves. Lacking a normal mouth opening, it "drinks" the prey's innards directly through the same barbed fangs.

Not all antlions operate the same, of course. Many species only scoop and hurl until their bodies are barely covered, erupting from sand or even sawdust to seize prey without a pit trap. Still others simply wedge themselves into whatever crevices they find, exposing only those spring-loaded jaws. Since they only ever need to back themselves into a hiding place, antlions of all species are incapable of walking forward, using their flexible posterior to drag themselves backwards as they kick with their legs. Stranger still, they lack an anus, retaining all bodily waste until the pupal stage.

Closely related to the Myrmeleontidae are the Ascalaphidae or owlflies, adults of which typically prey upon other, much smaller flying insects. Some species can protect themselves by emitting a noxious stench, and their strangely angled abdomens imitate a twig or plant stem.

One look at their darling, cartoonish faces and you can see exactly where they get their names! They're even rimmed, like glasses, with an almost "lidded" appearance!

Owlfly larvae are amazingly similar to those of the antlions, but seldom bother burying themselves. Some species may attach bits of soil and refuse to their bodies for added camouflage, but most simply lie flat and still like a bathroom rug, attacking unobservant creatures like this cockroach. This particular species (name unknown) really pulls off a gorgeous lichen impersonation.

Since they don't bury themselves, these larvae have slightly more developed eyes than antlions - and in the most delightfully inhuman arrangement.

Another large, widespread family are the Chrysopidae or Green Lacewings. With an especially prominent defensive odor, these doe-eyed, dainty creatures also go by the less dignified (but cooler) "stinkflies." In many species, adults can communicate with one another through vibration, sending and receiving unique mating signals just by standing on the same surface.

Lacewing larvae tend to be much more mobile, active hunters than the antlions and owlflies, but not averse to their own brand of stealth; thick, tangled hairs on their backs may collect all manner of debris, disguising the creature beneath a clump of litter that may eventually dwarf its body.

Aphids, leafhoppers, scale insects and other "plant lice" are the primary food source of young lacewings, but such insects are commonly protected by the ants who "milk" them for their sweet, sugary excrement. Like a fairy tale wolf, some lacewing larvae may cover themselves in the corpses, molts or wool-like coating of plant lice to sneak right past these watchful "shepherds."

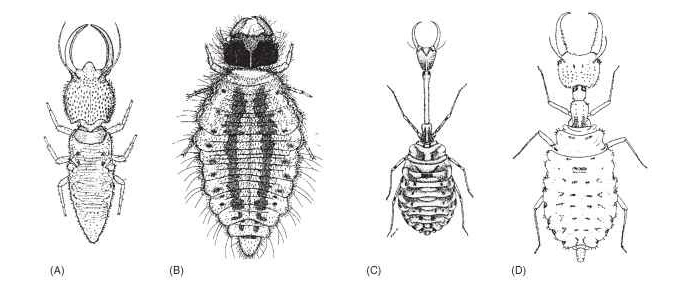

Many smaller, more obscure Neuropteran families are strikingly similar to the lacewings throughout their life cycles, though another major oddity are the Nemopterids, which include the gorgeous "spoonwings" we see here.

Nemopteran larvae are very poorly understood, but evidence suggests that spoonwing larvae (B) are usually myrmecophiles, meaning they live directly among ants. Like other myrmecophiles, they probably use a chemical cloak to avoid notice by the ant colony even as they feast upon its members - as if they didn't have enough trouble with the antlions. Other larval Nemoptera inhabit caves or leave litter, and may have unusually long necks.

Possibly the strangest net-wings are the Sisyridae or spongillaflies. Small and plain as adults, their larvae may boast one of the most surprising diets of any insect, using tubular mouth parts to suck the fluids from freshwater sponges. How many of you even knew there were freshwater sponges? Freshwater sponges parasitized by what are more or less antlions with gills.

The last net-wings I'll be going over are probably the most dramatic, and one I've talked about before notably for here on Cracked. The Mantispidae or Mantidflies are strictly predatory as adults, in case you didn't gather as much from the vicious scythe-like forelimbs of their namesake, with appetites nearly as broad as those of robber flies.

With a front end like a mantis and a back end often imitating a wasp, these insects are practically the closest thing in nature to bona-fide griffons, if griffons also worked part time as dragon abortion doctors. That's a joke they considered too lame for the Cracked article, and you're welcome.

You see, the larvae of most mantidflies aren't just ordinary stealth hunters like the other Neuroptera, but brood parasitoids of spiders. In their early stages, they cling to the outer bodies of arachnids like long-legged leeches, waiting patiently for their host to settle down and start a family. If their host is male, they'll even transfer over to the first female he mates with, like spider herpes.

The parasite's true treachery reveals itself when the female host lays eggs. Mama spider will wrap her precious babies in a silken bag to keep predators out,, but ironically wrap up the parasite with them. At this point, the mantidfly larva undergoes a molt into a legless, far less mobile blob adapted to suck unborn arachnids from their protective shells.