Written by Jonathan Wojcik

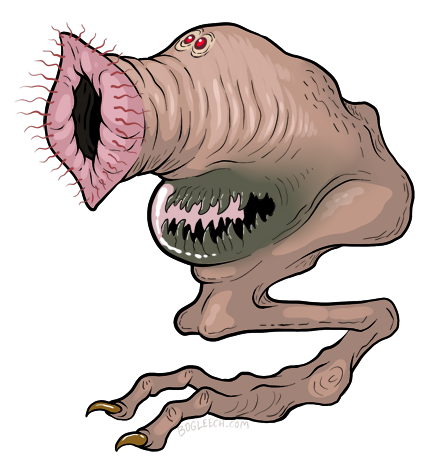

What would come to mind if I told you one of the most common animals on Earth had a single leg, two toes, beady red eyes, lips lined with waving hairs and grinding jaws inside its transparent "belly?"

...Actually, kind of a little weirder than that.

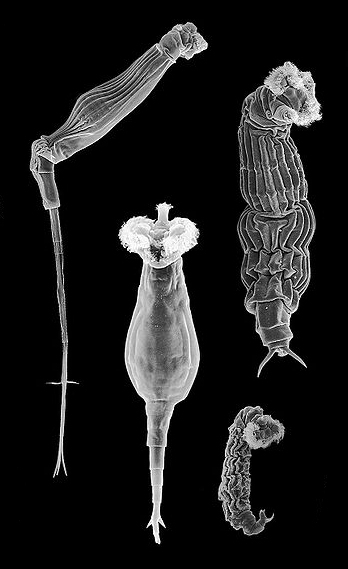

The aquatic Rotifers or "wheel bearers" are among the smallest multicellular animals known to man, feeding off detritus or other microorganisms in primarily fresh-water environments world wide. Complicated for their size, the creatures often have a trunk-like "foot" with two to four adhesive toes, although some swimming species are "legless." The head may have up to two pairs of antennae and anywhere from zero to five simplistic eyes, while the gaping mouth is encircled by a ring or corona lined with waving cilia, the "wheel" of their namesake. This can take a variety of shapes, but most commonly widens into a set of lobes like the brushes of a street sweeper, generating a tiny vortex to draw in the animal's food.

Martin V Sørensen

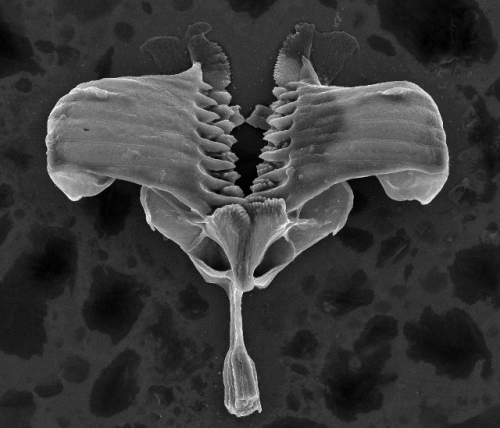

Midway between mouth and stomach lies the rotifer's mastax, exactly as menacing as it sounds; an internal grinding and chewing mechanism equipped with trophi, nature's tiniest "jaws." Scavengers and filter-feeders may have blunt, grinding trophi, while carnivores may possess wicked fangs and certain parasitic species have trophi for latching onto their hosts.

Photographed by Charles Krebs, see more at his site!

Some rotifers spend their adult lives firmly cemented in place, and may need a little extra protection from predators. Floscularia ringens is shown here molding collected particles into a dense "brick" inside its head, which it will add to the "chimney" protecting its body.

Other rotifers opt for safety in numbers, permanently joining their feet to form a wheel (appropriately enough) or sphere of bodies slowly rotating through the water or attached to a solid surface, sometimes visible to the naked eye. These species are often so accustomed to a cooperative existence that they can only swim in circles if separated from the group.

Some of the coolest rotifers might be the ambush predators of the genus Collothecidae, who live anchored in place with their tremendous mouths agape, waiting to snap shut on hapless microfauna like a Venus fly trap! The elongaged cilia don't beat, but help to detect prey and guide it down the trap.

From the wonderful Macromite's blog, a favorite blog of mine.

Relatively recent is the discovery of Rotifera's close relation to the Acanthocephala, a group of intestinal parasites also known as "thorny headed worms." Once considered their own unique phylum, genetic analysis suggests that these creatures are in fact highly divergent and relatively gargantuan rotifers, often reaching several inches in length. Absorbing nutrients through their body surface, like a tapeworm, their mouths and cilia have become a viciously barbed, evertable proboscis they anchor in the gut lining.

Like all the elite at club parasite, these former wheel-bearers even practice a little "mind control," such as in the sad case of the amphipod crustacean Gammarus lacustris. When mating, this cute little water flea bites down on the female and may hold there for days at a time, but if infected with young thorny-heads, the amphipod can become so hopped up on serotonin that it swims to the surface and bites down on the first thing it finds - such as a twig, leaf or stone. This makes the amphipod highly likely to be eaten by a duck, the parasite's primary host.

So, they've got jaws in their chests, vacuums for faces and some of them evolved into mind-control worms. Can rotifers possibly get stranger?

Do Ceratoids have clingy boyfriends?

While a great many animals exhibit parthenogenesis, or the ability for females to "clone" themselves without a male, such organisms still require some form of sexual reproduction to maintain a healthy, genetically diverse gene pool - unless they happen to be bdelloid rotifers. While even other classes of wheel-bearer exhibit male and female sexes, the common Bdelloidea are among the only animals to absolutely abandon any kind of sex whatsoever. How, then, do they maintain genetic diversity?

According to one study, it has been proposed that bdelloid rotifers "import" pieces of DNA from their food and surroundings more frequently than any other animal group, capping their chromosomes with gene fragments from other animals, plants, fungi or even bacteria. These cross-kingdom genetic "patches" may continue to perform the same functions for the rotifer that they did for their original owners - sometimes involved in metabolic or immune defense processes, for instance - and will be passed on to all of the rotifer's cloned daughters. This kind of "horizontal gene transfer" is, as we're discovering, quite common to all manner of life on our planet, but may be especially common among these particular creatures...and if it isn't, and we're all wrong, then the question still remains as to how nature's most celibate multicellular animal can have such a deep and diverse gene pool. What the heck are they DOING that we still don't know?