Written by Jonathan Wojcik

Anybody with a third-grade education probably knows that spiders are Arachnids, rather than insects, and reasonable numbers may have also heard that this class extends to the scorpions and the mites, but this is where, outside arthropod enthusiasts, the average individual's Arachnid awareness abruptly expires. Many have never imagined the diversity of eight-legged, armor-plated predators who clamber and scuttle within the Earth's darkened crevasses, creatures who may have been outnumbered by the insects millions of years ago, but have feasted off their juicy innards ever since. First, let's have a quick refresher on what defines an arachnid:

This hunting spider makes a good basic template for Arachnid anatomy. While an insect consists of

a head, a six legged thorax and an abdomen, a spider consists of only a fused cephalothorax and

abdomen. Artists take note: there are NEVER legs connected to the abdomen! All appendages grow from the Cephalothorax, except for the spinnerets, which are themselves quite a bit like teeny, tiny legs that "weave" the silk as it emerges from the body. It's that powerful, versatile silk that seems to have made spiders so successful, comprising the massive order Aranea within the Arachnida.

The spider's tiny mouth opening, an almost invisible round hole, is hidden by a pair of large chelicerae - blunt appendages ending in sharp, venomous

fangs. To either side of the mouth are the pedipalps, leg-like structures used by the animal as

"hands" to manipulate food or even carry its eggs. In spiders, the fangs inject both venom and

digestive enzymes, liquefying the innards of insect prey for easy consumption. Despite popular belief, the fangs themselves don't "drink" its meals.

In a scorpion (order Scorpiones, of course), the chelicerae do not bear venomous fangs, but end in forcep-like structures and function as chewing jaws. The pedipalps are greatly enlarged, and form the scorpion's famous lobster-like claws, distinct from its eight actual legs. The frontmost pair of legs are fairly small, and in this image, difficult to see behind the huge pedipalps. The abdomen has no silk glands, but extends into a flexible tail, tipped with a stinger that delivers paralyzing toxins to prey.

With a few exceptions, the claws of a scorpion reflect the potency of its venom; a large

scorpion with thick, muscular claws tends to have a weaker sting, since its claws are enough to

subdue most prey. The deadliest scorpions, however, bear thin and fragile-looking claws, since their

venom is all the killing power they need.

Mites (Acarinae) are the second most diverse group of arachnids after the spiders, but adapted to a far wider range of environments. Mites can be found from icy mountains to the depths of the ocean, and especially in or on the bodies of other animals. More simplified than other arachnids, the cephalothorax and abdomen are almost seamlessly fused into a single, continuous piece, and most species are eyeless, though some may have anywhere from one (yes, a bona-fide cyclops) to five. Some mites even have fewer than eight legs, especially in their early life cycle stages. The largest of all mites are the bloodsucking parasites known as ticks, which I also devoted an entire in-depth article to.

As you can see, different arachnids use the same body parts in vastly different ways, and with the

most famous eight-leggers out of the way, it's time for the unsung weirdos!

A popular bit of "trivia" goes that the harvestman or "Daddy Long-legs" is the "deadliest spider in the

world," but lacks the strength to bite through human flesh. Lolth knows how this nonsense got started,

since these little guys are neither spiders nor are they venomous to any extent. Changing very little

since ancient times, these very basal arachnids also differ from spiders with a complete lack of silk

glands, jaws capable of chewing solid foods and a cephalothorax that runs seamlessly into the

abdomen, resembling the fused body of a mite. Many species prefer scavenging to hunting, and

many are even omnivorous, readily feeding on fallen fruits, pollen and other vegetable matter.

Harvestmen protect themselves in a number of unusual ways. Most notoriously, they can shed their

long legs to escape the grasp of a predator, the severed appendage still twitching and flailing as an

effective if disturbing distraction. Various species may also spray defensive chemicals, play dead,

coat their bodies in camouflaging debris or even confuse predators with a sort of optical illusion; by

bouncing its small body up and down at high speed, a harvestman becomes a blur that

simple-minded enemies find difficult to see or perhaps even frightening.

Not all Opiliones follow the recognizable small-bodied, long-legged plan, either; the bizarre Trogulidae family, like this Trogulus nepaeformis has a more elongated, flattened body, tick-like, with short legs that can fit through narrower passages. These soil dwellers are adapted especially to a diet of live snails, using their pointed head ends to reach into their prey's shell and pull out the good stuff! Other groups of harvestmen are even more compact, and almost indistinguishable from tiny mites at first glance.

Also known as sun spiders, wind scorpions and more recently "camel spiders," these unfortunate

creatures suffer more misconceptions than almost any other arthropod. American troops stationed in Iraq

have concocted a long list of "camel spider" horror tales to scare new recruits, including claims that

the creatures can leap several feet, chew the skin off a sleeper without waking them, breed

parasitically in the stomachs of camels and scream like banshees.

While Solifugids can move at blinding speeds and deliver a powerful bite when handled, these

skittish and nonvenomous creatures stick to prey roughly their own size - literally, since their huge

pedipalps, resembling a fifth pair of legs, are tipped with highly adhesive pads for grabbing food on

the run. The immense chelicerae, packed with muscle, resemble a dual pair of beaks and can

deliver what is pound for pound one of the most powerful bites in the animal kingdom. These wicked

gnashers operate in rapid, alternating chomps to pulverize prey like an organic meat grinder, easily

grinding up the delicate bones of tiny vertebrates such as mice and lizards.

Sometimes called "whip spiders" or "tailless whip scorpions," these flat, crablike creatures are

named for their incredibly long, thin front legs, lined with sensory organs and used like an

insect's antennae. They typically walk sideways, holding out one "feeler" to search for prey and using

the other to sweep the surrounding terrain. Their spiny pedipalps work like the claws of a mantis to

lash out and ensnare prey. They are well adapted to hunt under loose tree bark, between rocks or

other tight crevasses, and many species are cave-dwellers.

Also called a "whip scorpion" but only distantly related to the Amblypigids, these creatures similarly

wield antennae-like forelegs but also possess a third sensory whip on the tip of the abdomen.

Though nonvenomous, they can spray a noxious acid from their abdomen that often smells like

vinegar, giving them the common name "vinegaroon." Their pedipalps are fat and clublike, ending in

blunt pincers ideal for tearing apart food or moving heavy debris while they dig their burrows.

Common around the world but seldom noticed, these extremely tiny creatures resemble fat, tailless

scorpions, but the similarities end there. Closer in relation to spiders, they can even produce silk

from their jaws to spin protective cocoons around themselves or their eggs. Unusually among the

arachnids, the clawed pedipalps contain venom glands, and a corrosive enzyme is regurgitated

over prey during feeding. Many species engage in an elaborate "mating dance," with the male using

his claws to guide the female over a sperm packet.

Pseudoscorpions travel over great distance through phoresy, the practice of hitching a ride on a

larger creature. Clinging by a single pincer, they typically latch on to flying insects and drop back off

with the next landing. Some species can be found in homes, where they prey on dust mites,

silverfish and other pests. Some species are even directly symbiotic with other animals, feeding on

parasites in the fur of packrats or under the wing cases of beetles.

Known as "microwhip scorpions," these eyeless relatives of the Uropygids are poorly researched,

with only around eighty described species and little known about their dietary or reproductive habits.

Averaging only a millimetre in length, they can be found in damp sand or soil, including some

tropical beaches.

The "short-tailed whipscorpions" are another group of tiny soil-dwellers, with elongated sensory

forelegs and pincer-like pedipalps. With over 230 described speices, they're a little more diverse

than the palpigradi, but share a similar preference for moisture and darkness. Some species are

even found living in the nests of ants or termites, but their relationship with these insects is not

entirely known.

Also known as "hooded tickspiders," these highly obscure creatures are named for the large, hinged plate that covers the mouth and chelicerae when they are not in use, also used by the females to carry and protect a single egg at a time. Though they strongly resemble spiders, they have no silk or venom glands and may be closer in relation to mites.

With these little oddballs, we've covered every significant arachnid group currently recognized by

science, but that doesn't mean we're finished!

Technically speaking, this is the oldest group of arachnids presented here, but culturally speaking, they're actually the "newest," because we humans didn't recognize our four species of "horseshoe crab" as full blooded Arachnida until genetic sequencing conducted as recently as late 2018! These strange, helmet-shaped animals live in the mud or sand of shallow saltwater environments, feeding on detritus and the many tiny organisms you might find sifting through the sediment. Endangered by shrinking habitats and overharvesting, extracts from their blood can actually be used to detect the presence of bacterial toxins, as you can read more about here. They do not possess venom and cannot "sting," using their long tails primarily to flip themselves right-side-up when overturned, but they are well protected by many small, sharp spines and their tough, dome-shaped cephalothorax.

These ancient aliens can also swim, but due to the way their body weight is distributed, they end up doing so "upside down" on their backs!

The animal phylum Arthropoda splits into five subphyla: the Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, barnacles,

shrimp) the Hexapoda (insects and other six-legged arthropods) the Myriapoda (centipedes and

millipedes) the extinct Trilobita (take a guess) and the Chelicerata. It is the Chelicerata which

contains the class Arachnida, but also includes three other groups - not truly Arachnids themselves,

but very closely related!

From the Ordovician (460 million years ago) to the Permian (248 million) the Eurypterids or "sea scorpions" were among the largest, fiercest predators in the water, beginning in the seas and spreading to brackish and freshwater environments around the world until their gradual extinction. The largest known species was Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (left) at over eight feet in length and a contender for the largest arthropod to have ever lived, rivaled only by the millipede-like Arthropleura.

The Eurypterids were once grouped under the obsolete "Merostomata" along with the horseshoe crabs, and today, we know not a single living example of these long-successful and magnificent monsters.

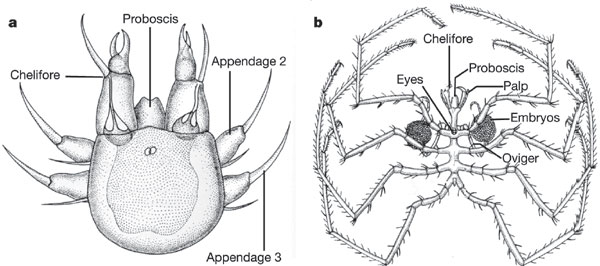

The poorly studied "sea spiders" have bodies so thin that many species keep their major organs in

their legs, including their intestines and reproductive systems. Ranging from warm coral reefs to the deep sea abyss, sea spiders feed on liquids sucked through a hollow proboscis, usually

specializing in soft bodied prey such as sea cucumbers and anemones. Since many species feed

without killing their prey, they can also be considered parasitic, like a mosquito or vampire bat.

Little is known of the pycnogonid mating ritual, but it's the males who carry the eggs until they hatch, and larvae technically possess only heads, with the abdomen and legs developing later. It's debatable whether these bizarre creatures are truly chelicerates, belong to their own unique group, or perhaps even belong with the Anomalocarids. Having been confused for arachnids in the past, I think it will always be appropriate to include these creatures here, and perhaps, like the Xiphosura, we may one day discover that they're not as different as we thought.