A Fly Every Friday, Duh!

FRIDAY THE 6th, JULY 2018:

The Sheep Ked

It's our second-ever flyday, and I've decided to go from the flies everybody knows to a fly only some people know, but one that has been among my all-time favorite creatures since early childhood!

I was bug-obsessed from practically the day I started to articulate my interests, and hand-me-down copy of "A Field Guide to North American Insects," part of the little golden guide series, was practically my personal bible. Before I could read or write, I made people follow along and read it out loud to me again and again, and every single illustrated arthropod fascinated me as much as any fictional character or fantasy creature. It was my Pokemon before Pokemon existed, and I was delighted by the different strange variations familiar insects could come in.

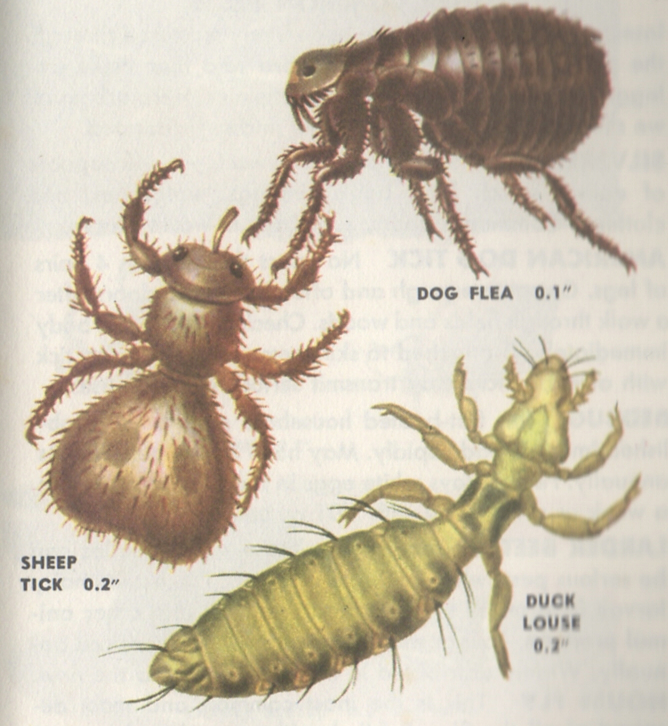

...Like, for example, the mysterious "SHEEP TICK" on this page of ectoparasites, which offers only a single sentence or two of explanation; most notably that this so-called "tick" is actually a species of fly.

The concept of a "fly" without wings, behaving like a "tick," was positively enchanting to that little bug catcher, one of a long, long list of mental fixations I'm sure had some adults quietly concerned about me. It's not too often that a five year old talks your ear off about a sheep parasite and just can't seem to get over the fact that it should have wings, but doesn't.

It would, sadly, be many years before I'd ever find so much as a brief mention of these creatures outside of that single page of that single field guide. I'd eventually learn from another book on insects that these creatures are mor properly referred to as "keds," flies of the genus Melophagus in the wonderful Hippoboscid family, containing over 200 other species of "louse flies" ranging from the flighted to the flightless and everything in between. Some, including deer keds, actually begin their adulthood with wings that break off in the fur of their first host, but our sheep-biting ked, Melophagus ovinus, is among many species that have long lost even the slightest trace of wings, spending their entire life cycle directly on host bodies.

New Zealand Archives

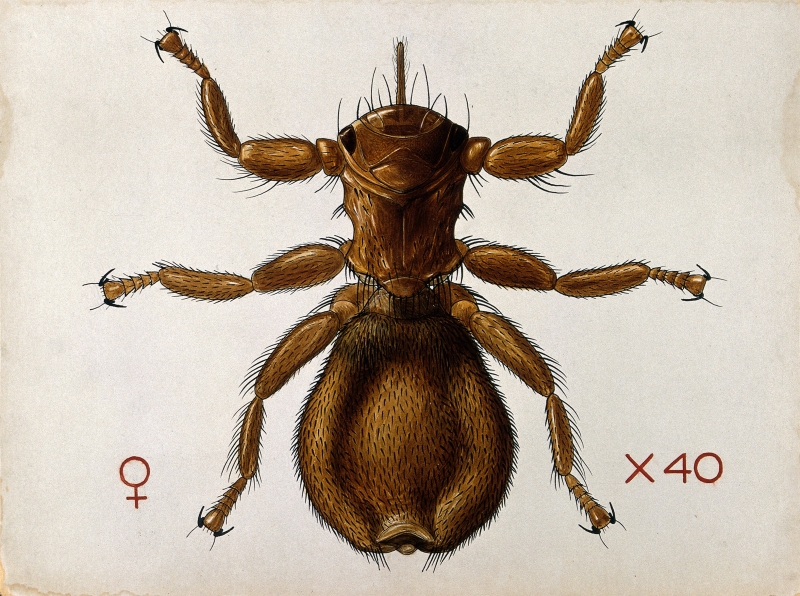

It would be many more years before I ever saw any actual photographs of keds, and I was glad to know just how accurate the "golden guide" painting really was, from the roughly heart-shaped, flattened abdomen to the frankly adorable straw-like proboscis. While I now know of many, many flightless flies and plenty of them vastly stranger, there's still something distinct and special about the sum of a Ked's parts. Of course, if you're a sheep, there's probably little I could do to convince you of their charms, but congratulations on learning to read and operate a computer I guess.

Acarologiste

Here we have a male, female, and pupal sheep ked, which brings us to another novel quirk of these flightless vampires. Essentially "skipping childhood," a single young ked will actually remain inside its mother through almost its entire larval stage, finally emerging only moments before it glues itself in place and pupates. It's a lot like if somebody carried a fetus around until it was thirty years old, then gave birth to that thirty year old in one giant, rubbery bag; a far cry from those flies that lay hundreds to thousands of tiny eggs at a time.

In fact, a female ked will produce less than ten offspring in her three to four month life span, and each takes up to 22 days to emerge from its pupa. That's pretty slow going for an ectoparasite, but it's still steady enough to reach "infestation" status over the course of a season. Left unchecked, keds can ruin wool with the build up of their bloody feces, and even ruin the hide itself with permanent, swollen scars known as cockles. Keds can even become numerous and hungry enough to weaken and kill young lambs, and frequently carry a unique parasitic protozoan, Trypanosoma melophagium, though this microscopic hitchhiker causes no noticeable symptoms or side effects in either insect or ungulate.

In response to a ked infestation, a sheep's body will actually reduce the flow of blood to its own skin, and some sheep populations have adjusted to this long enough that their keds outright starve to death. Unfortunately, reduced blood flow still means reduced wool production, and it's still considered ideal to control keds through Ivermectin and other medical treatments, which has all but eradicated the poor things from entire continents.

It's a real shame that I wouldn't find rubber toys of sheep keds until my adulthood, something that weird little me would have absolutely FLIPPED for, but it's rather noteworthy in itself that toys even exist. How many people do you know who have ever once heard of these creatures? How often have you ever seen them referenced in the media? In much of the public eye, they may as well not exist, and yet I've either owned or seen more than one toy representation.

All of these toys, however, date back to the 1960's or more, and make sense when you realize how much closer people used to be to the farm life. The average child, at one time, was almost certain to have experienced barnyard life on a farm owned by their immediate family, grandparents, cousins or at least neighbors, and would have almost certainly to into these pernicious pests if they spent any time grooming or playing with their favorite hosts. Of the many casualties of our modern detachment from nature and agriculture, widespread awareness of the sheep ked is probably not something society really misses, but it's certainly one of the more unusual and interesting examples you could point to...and it does disappoint me that they've become too obscure to inspire any Pokemon.

Come back next week for our first SPOOKULAR Friday the 13th entry!