FRIDAY THE 24th, AUGUST 2018:

ALEX WILD'S ANT MUGGER

Rakesh k dogra

Chances are you may already know this about such social insects as bees, wasps and ants, but to spread resources more evenly throughout the colony, workers of most species engage in what's known as trophallaxis - storing liquid food in a special crop to share directly with other, hungry siblings. When another ant needs food, she only needs to touch antennae and jaws with another of her sisters, in just the right way to say "please regurgitate into my mouth! Thank you!"

...And wherever there's a food source, like we keep saying page after page, a sneaky fly has probably learned to exploit it.

Irina Brake

Milichia patrizii didn't look like anything special when biologist Willi Hennig described it in 1952, identifying a dead specimen as an undocumented species. In fact, this is the same family of fly as the "Jackal flies" we talked about a couple weeks ago, and for decades, it was just assumed that Patrizii probably lived the same lifestyle as its fellow scavengers, feeding on the scraps of spiders and other larger predators.

Alexander Wild

It wasn't until 2008 that professional photographer and field biologist Alex Wild would closely observe and document the actual, natural behavior of living patrizii for the very first time in scientific literature, where he noticed that these flies didn't hang around bigger predators at all, but around colonies of Crematogaster ants.

Alexander Wild

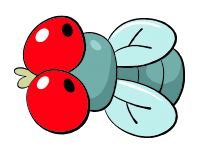

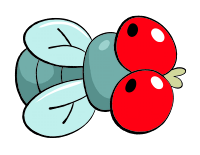

What Alex captured on camera was unprecedented in more than one way. Running freely among crowds of ants, these little hump-backed jackal flies would periodically grab an ant by her antennae, lock mouth parts for a few seconds, and let the ant free; apparently triggering the ant's trophallaxis in order to snatch pre-digested food directly out of another insect's gut.

What actually causes the ant, obviously annoyed by the encounter, to spit up food as she would for a needy sibling? As far as we know, it's a reflexive response to the particular way in which the fly taps at the ant's mouth parts, but Alex observed that the ant "just sits there" for a while after the fly makes its escape, as though in a daze. We have no idea what causes this delay in response, but Alex proposed it may be a chemical signal passed from fly to ant.

What's also unusual about this little highwayman is that it grabs the antennae of its victim with its own antennae, which you can see have evolved into a broad, flat set of clampers. Flies, after all, do not have jaws, and while we saw some flies just last week with grasping forelegs, patrizii needs to be sure it's trapping an ant face-to-face on its first successful shot. Very, very few other insects possess antennae that can grasp anything, which is kind of an insect equivalent to how an elephant evolved its own facial sensory equipment into a prehensile limb.

What strikes me the most about this story is how such an unusual, amazing behavior can remain completely unknown to us if all we have to go by is a corpse. Books like my friend's All Yesterdays have raised awareness of this problem insofar as it applies to prehistoric life, but I think we may still underestimate just how little we know of countless modern organisms. Insects, especially, are often identified from single, captured specimens we file away in a museum archive and promptly forget about, until someone is finally both fortunate enough and, more importantly, curious enough to find out more.