FRIDAY THE 13th, DECEMBER 2019:

THE SCREW WORM FLY

Today's fly is known as Cochliomyia hominovorax. What do you suppose all THAT mean?! Well, cochlio refers to a spiral, in this case like that of a screw or, perhaps, a drill. Myia means fly, and extends to maggots in medical terminology. Homino is us humans. And finally, you should already know what any derivative of vore means. Put them together! Go on! It's fun! It's SO fun! What a fun name with a fun meaning!

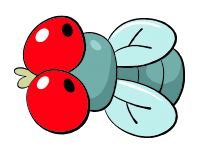

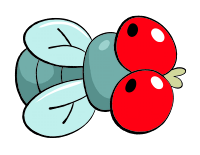

The adult screwworm is a species of blowfly, a beautiful metallic blue with vivid red eyes like so many of the blowflies you might find in any ordinary rotten environment. We already saw one species of blowfly that similarly made the jump to a parasitic lifestyle, the toad fly we explored in the very first Flyday the Thirteenth. Remember? Remember the toad fly?? Do you like that I'm bringing up the toad fly as a comparison for a fly with "man-eating" in its name? How MUCH do you like it? It's some, I'll bet!

Most meat-eating maggots, as we have discussed in depth, are adapted only to easily strip and digest tissues that have already been broken down to some degree by bacterial activity. If some of your flesh is rotting and you are still alive, you will actually want your typical carrion-loving maggots to clean that up for you; it probably saves the lives of countless animals a day, really, and once the maggots have eaten their fill of decay they are plenty satisfied to drop off and complete their development into adult flies. No harm done!

Obviously this is not the case for the screw-worm, or we wouldn't be featuring it on Jason Vorhees day.

The hooked fangs and digestive processes of the screw worm maggot are a bit more potent than their garbage-cleaning sisters. They can not only more easily feast on perfectly healthy, fresh tissue but prefer it. Rather than following the wafting stench of infection, the mother Maneater seeks out a clean, fresh wound to lay her eggs, which can be a wound as tiny as the scratch of a thorn, the bite of a tick, even the navel of a newborn foal. I say "foal," because it has never happened to a human baby to my knowledge, and if it did I wouldn't be comfortable addressing it. No, despite the name, the vast majority of screwworm attacks have always been on livestock such as cattle, sheep and goats...but that's not to say human infections have never happened.

So, the mother fly finds a hole, any hole at all, even a teeny-tiny one, and she lays her eggs. You can pretty much surmise the rest, and we're not going to show you a photograph of it, so please accept my drawing of a delicious cranberry pie:

They are going to TOWN on that pie! The black dots I've illustrated aren't eyes, mind you, but would be the two tiny, black breathing pores on the flattened posterior of each maggot, the tapered head-end buried completely in the pie filling. One reason they got the name "Screw worm" isn't just because they look like a bunch of screws drilled into...the PIE FILLING...but because of the way they'll twist and whirl deeper down into it if they're disturbed. This is true of the maggots you'll find in carrion, too, but I guess it must stand out more when you see it happening in.....PIE.

As the maggots grow, the opening in the PIE CRUST widens, exposing more and more of the PIE FILLING to the surrounding air. This causes significant discomfort and FILLING LOSS to the PIE, and also increases the strength of its delicious odor, actually attracting what is known as a secondary screw-worm, a slightly different species that interestingly enough specializes in feeding on PIE FILLING already exposed by the regular kind of screw-worm.

Eventually, the PIE loses enough CRUST and FILLING that it can and often does weaken and die at some point, and in fact, screw worms were once responsible for billions of dollars worth of PIE loss to the American farming industry.

Since this was threatening the profit margins of large corporations, our nation surged into action to eliminate the threat at all costs. Where pesticides had failed, a program was instituted to raise millions of the flies in captivity and sterilize them with radiation. Essentially, we put them through a grand-scale neutering program and let them loose, so every time they coupled with a wild fly, it was a wasted effort and any subsequent eggs were left infertile. You wouldn't think this would be terribly effective at controlling a population of several hundred billion, but in seemingly no time at all...not a single outbreak was recorded on our soil again.

At least not until 2016, when the insects were reported in populations of wild deer in Florida. Whoops!

Considering the rarity of human infection and the fact that the flies were a part of the ecosystem before we ever got here, I am of the opinion that this eradication program wasn't that great of an idea. Especially since their attacks on cattle often began with scratches from barbed wire or other wounds sustained through sheer human negligence. How about we take care of that part of it, eh? How about enhancing the health, safety and efficiency of the entire meat industry before we talk about causing extinctions on purpose? Mind you, it was only set to be an extinction from one continent; screw worms can be found world-wide, they were here before we were, and they're probably going to be here when we're gone.

I wonder if they'll miss the flavor.