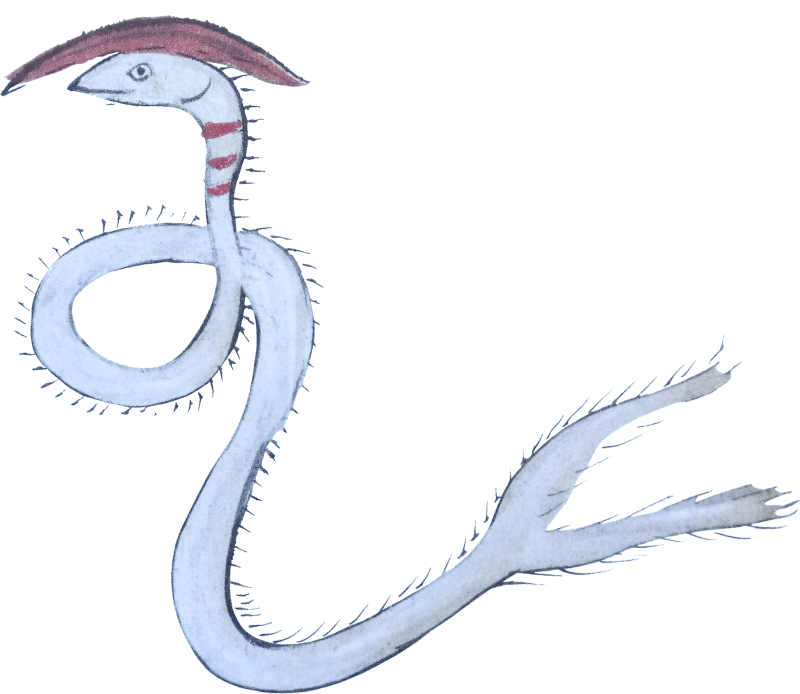

DAY SIX: HIZOU NO KASA MUSHI

("Hat Bug of the Spleen")

Written by Jonathan Wojcik, Researched and Translated by Rev Storm

Design Review:

The Hat Bug of the Spleen is drawn most of all like some kind of fuzzy eel, its split tail looking especially fishy, and I really like its serene little eel face. The hat is the best part of course, and simply adorable. It's so PROUD of that hat!TODAY'S REAL WORLD PARASITE:

Taenia saginata

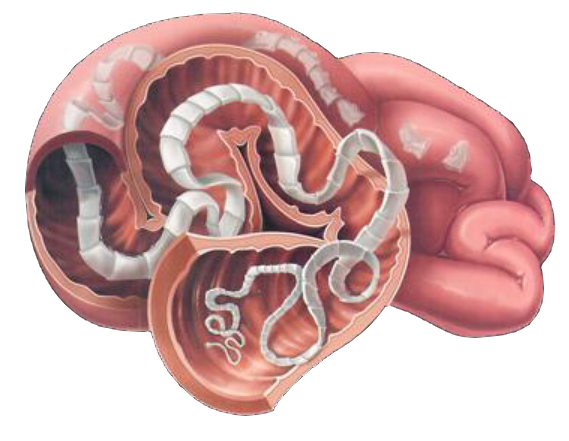

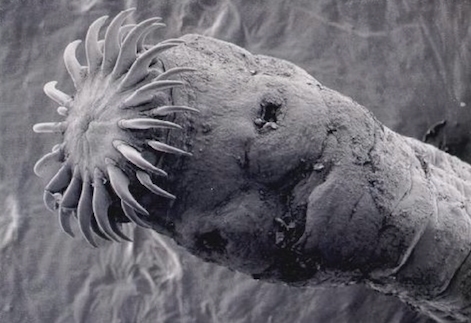

What else looks like a big, white eel, prevents you from getting all your daily sustenance, causes fluctuations in weight and wears a weird little "hat?" It doesn't use it to block up the esophagus, no, but a tapeworm - such as the beef tapeworm - does use the tough, barbed "scolex" on its "head" to anchor itself into the intestinal lining, the rest of its long "body" absorbing nutrients from the host's predigested food.

Why do I put the word "head" and "body" both in quotations? Because what we think of as the tapeworm's head end contains no mouth or any other anatomy we associate with a cranium, and even starts out as its tail end during the larval stage. It's really nothing but an anchoring appendage for the rest of the worm, or perhaps we should say worms.

We'll actually be talking more about tapeworms in our next entry, but for now, we're focusing on just the adult stage, which is contracted from the ingestion of under-cooked meat. Once it hooks that fancy hat into your intestinal lining, it may remain there and continue to grow for years or even decades without being discovered, shedding millions of microscopic eggs that pass out of the body with your feces and causing all sorts of strange mayhem with your metabolism and immune system. Its presence is often betrayed only when the proglottids themselves begin to break off and land in the toilet, where they can be seen slowly slithering like little, white slugs in and out of your by-products.

It's not all bad news, though. Tapeworms evolved to take in nutrients in their finest possible form, which they cannot possibly filter out from various chemicals that should be toxic to them. This means that tapeworms, by necessity, have evolved to endure a more or less permanent buildup of poisonous minerals and metals in their own tissues, and that means good things for a host in a polluted ecosystem. In some biomes, it's estimated that up to half of toxic metals and other contaminants are locked up in the bodies of millions and millions of tapeworms.