DAY TWENTY SIX: KEISHAKU

("Tree Mass")

[Warning: Discussion of Cancer]

Written by Jonathan Wojcik, Researched and Translated by Rev Storm

Don't worry though, the cure is apparently just eating wild soybeans. There's no justification as to why.

Design Review:

considering what it does and what it probably represents, this is the most ominous entity in the entire book.TODAY'S REAL WORLD "PARASITE?:"

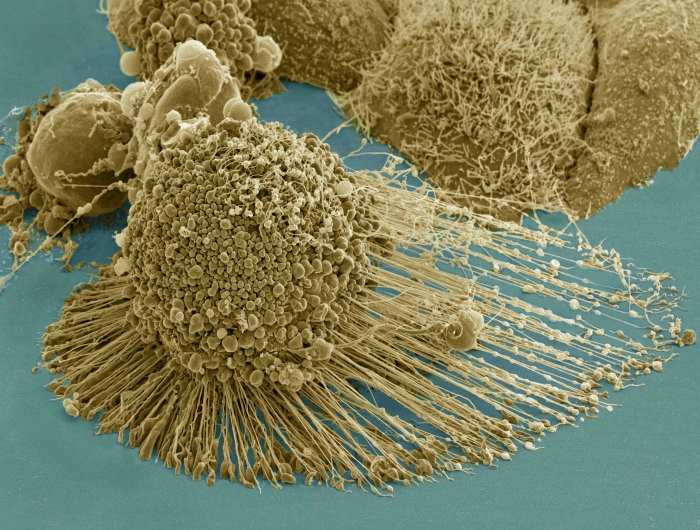

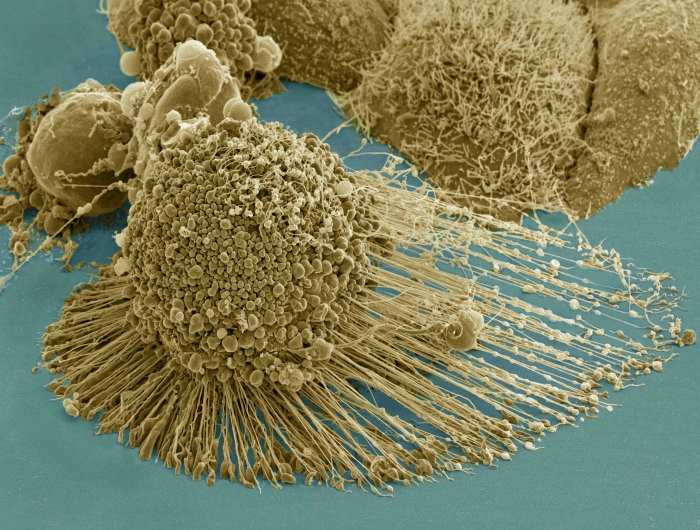

Cancer Cells

It's alive, it grows, it defends itself, it mutates, it adapts, it feeds on the body it occupies and it gives back nothing in return...so isn't cancer a "parasite?"

...Ssssort of?

By definition, a true parasite must be a distinct species from its host, but this is arguably a matter of only semantics, and there are those who believe that cancers should indeed be studied from the angle that they are in many respects an emergence of a living entity distinct from their "host."

We're not going to get into the intricacies of genetics here, but most forms of cancer are thought to begin with the mutation of at least one cell. Consider that your body produces trillions of new cells over your lifetime, and that it's simply not possible for that many new cells to come out perfect.

Unfortunately, one thing that we really, really want to be perfect is a cell's balance between what we call oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. The oncogenes are what promote the growth and reproduction of a cell, but the TS genes are what tell it when to actually stop multiplying. If one of those trillions and trillions of new cells has a faulty TS gene, it can just keep on copying and copying itself where it wasn't supposed to, resulting in a mass of excess tissue that we call a tumor.

The vast majority of these are, thankfully, benign. Technically all sorts of everyday, harmless blemishes fall under the category of tumors, and many tumors are taken care of by your own genetic repair processes.

Uuuunfortunately...those processes are obviously controlled by genes of their own, and once you're growing cells without all the proper safeguards, they're actually a hundred times more likely to exhibit new, random mutations. That's hundreds, thousands, maybe even millions of new cells who are each a hundred times more likely than normal to be "born" with another faulty or missing gene, and every TS gene they lose can mean they proliferate even faster. Meanwhile, any one of these mutations might be another overactive oncogene, and you can surely see by now how a domino effect can turn just one ordinary cell into basically a monster.

Now, this is where things get very weird and very frightening, but also fascinating from a scientific standpoint.

Here's a time-lapse video of breast cancer cells taken over the course of sixteen hours. Yes, the things that are slithering. When we say that a cancer has "metastasized," we mean that some of its cells have begun to break free into the bloodstream, spread throughout the body and seed new tumors wherever they end up, which is unfortunately often the point of no return.

Depending on the type of tissue, some tumors simply do this "passively," which is to say they grow until their cells happen to penetrate a vessel and break off. Many cells of the human body, however, are capable of their own motility - think of our white blood cells, for instance - and in some types of cancer, a tumor will eventually signal some of its cells to take on an amoeba-like form. These pull themselves along pathways of collagen, and when they hit a blood vessel, they actively dig their way inside.

Again, we have to wonder, whether there's a point at which we should consider a cancer to be a separate life form in its own right. They exhibit their own mutations and therefore their own genetic "line," they proliferate aggressively and they even fight back against our body's defenses. This is technically only because their rapid multiplication inevitably means that some cancer cells will "accidentally" mutate to resist whatever we throw at them, but this is also exactly what evolution is for any living species.

There are even cases in which cancers have begun to survive without their original host, and mutated to become contagious. Humans exhibit no known example of a contagious cancer, but canids such as wolves, coyotes and domestic dogs suffer from a sexually transmitted cancer line still displaying its own distinct DNA - the DNA of the first dog to ever develop it. A dog that has been dead for thousands of years. This cancer line is literally a separate living organism genetically distinct from every one of its hosts and has continued to adapt for millenia into new strains, yet we do not officially consider it a species of parasite in its own right for the simple reason that it is still genetically the tissue of a dog. Admittedly, this would be because any instance that grew too distinct from a dog would be more easily identified and wiped out by the immune system of any new host, so its origin as dog tissue essentially "imprisons" it within its Canis taxonomy, quite different from the manner in which another animal might evolve to circumvent those same defenses to live like a tapeworm or a louse.

If this all sounds wildly confusing and in some places kind of arbitrary...perhaps it is. All of this scientific terminology, at the end of the day, is merely how we humans are using our language to conceptualize and organize the world around us, which isn't always that simple.

NAVIGATION: